UKGlobal

27 January 2026

Renters are at the forefront of the housing crisis, suffering from decades of housing policy which has increased the financialisation of housing and benefitted landlords and homeowners at the expense of renters.

The UK housing crisis is not just a matter of a lack of supply. It’s a crisis of inequality and affordability, with renters bearing the brunt of its impact. Millions of renters face a daily struggle to secure stable, affordable housing, and remain stuck in an unaffordable private rental market due to decades of housing policy turning homes into assets. If we are to address this crisis, renters must be at the heart of any meaningful reform.

The new government proclaims to understand the nationwide hardship caused by the housing crisis, but Angela Rayner’s claim that “there are simply not enough homes” indicates that the government is either unwilling or unable to address its root causes. A serious plan to tackle the crisis requires a holistic approach which recognises that increasing supply should only form part of a much wider housing reform agenda that tackles the roots of the UK’s financialised housing system. There are systemic factors in the housing market which will continue to disproportionately affect renters if we do not address the questions of inequality, affordability and financialisation.

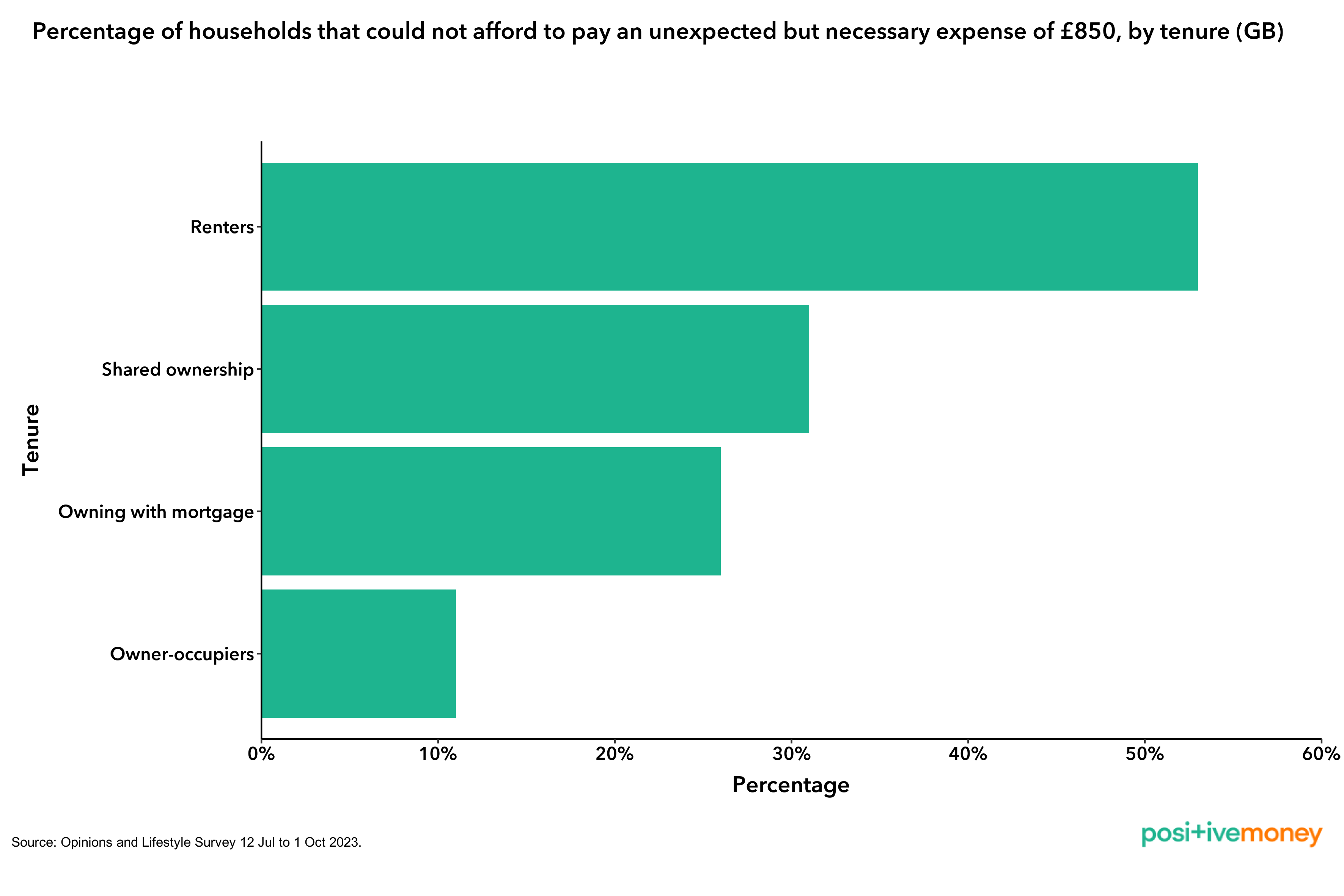

Only 10% of households in England lived in the private rental sector in 2000, but this has now increased to 19%. Even before the pandemic and the ensuing cost-of-living crisis, renters were in a far more precarious financial position than those in other forms of tenure. Only half of renters were able to cover a 25% reduction in income lasting for three months in 2020, compared to 78% of mortgage holders and 93% of outright homeowners who could cover the loss with savings. The financial precarity of renters has not improved since then, as less than half of renters were able to pay an unexpected but necessary expense of £850 in the second half of 2023.

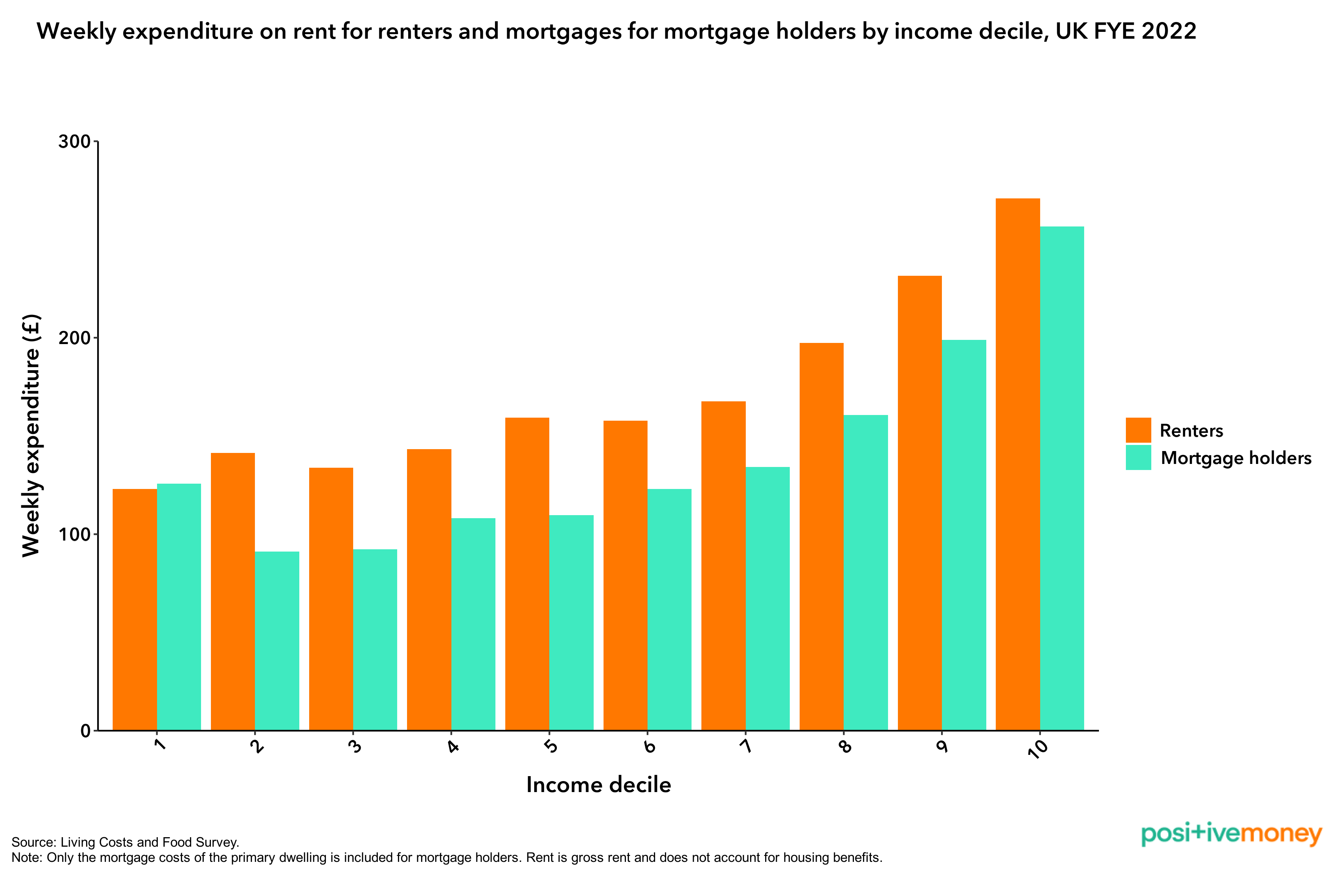

Furthermore, renters spend more on weekly housing costs than those paying a mortgage at every income decile except the lowest, underscoring the high cost of renting as a form of tenure. Renters from ethnic minority households are disproportionately impacted, spending a larger percentage of income on rent than those from a White background.

One in five UK tenants are forced to spend more than half of their income on rent. The median income of owner-occupiers is 141% higher than that of social renters, and 30% higher than that of private renters, revealing the drastically different financial situation of renters and those who own their home, either outright or with a mortgage.

Private renting is also an economically inefficient form of housing the population as it rewards unproductive rent extraction. The incentives of rental yields and rising property values shift economic resources and activity away from productive endeavours and towards rentierism. Productivity, innovation and wages will suffer as a result of rent extraction growing in proportion to the rest of the economy. However, the financial incentives are clear: the number of landlords has increased by 2 million since 1990 and stands at 2.5 million today.

Successive governments since Thatcher have made an increase in homeownership as the stated goal of housing policy, and legislation undertaken to promote this goal has had the impact of massively increasing property prices and landlordism while decimating social housing provision.

The liberalised mortgage market has led to 52.9% of total outstanding lending by banks now being held in mortgages, up from 38.4% in 2010. Other policies, such as exempting the sale of primary residences from capital gains tax, promoting homeownership through inflationary policies such as Help to Buy, and privatising 2 million social homes through Right to Buy has led to soaring house prices and a financialised housing market. Over 40% of council homes privatised through Right to Buy are now in the private rental market, where average rental costs are almost three times higher than rents in the social sector.

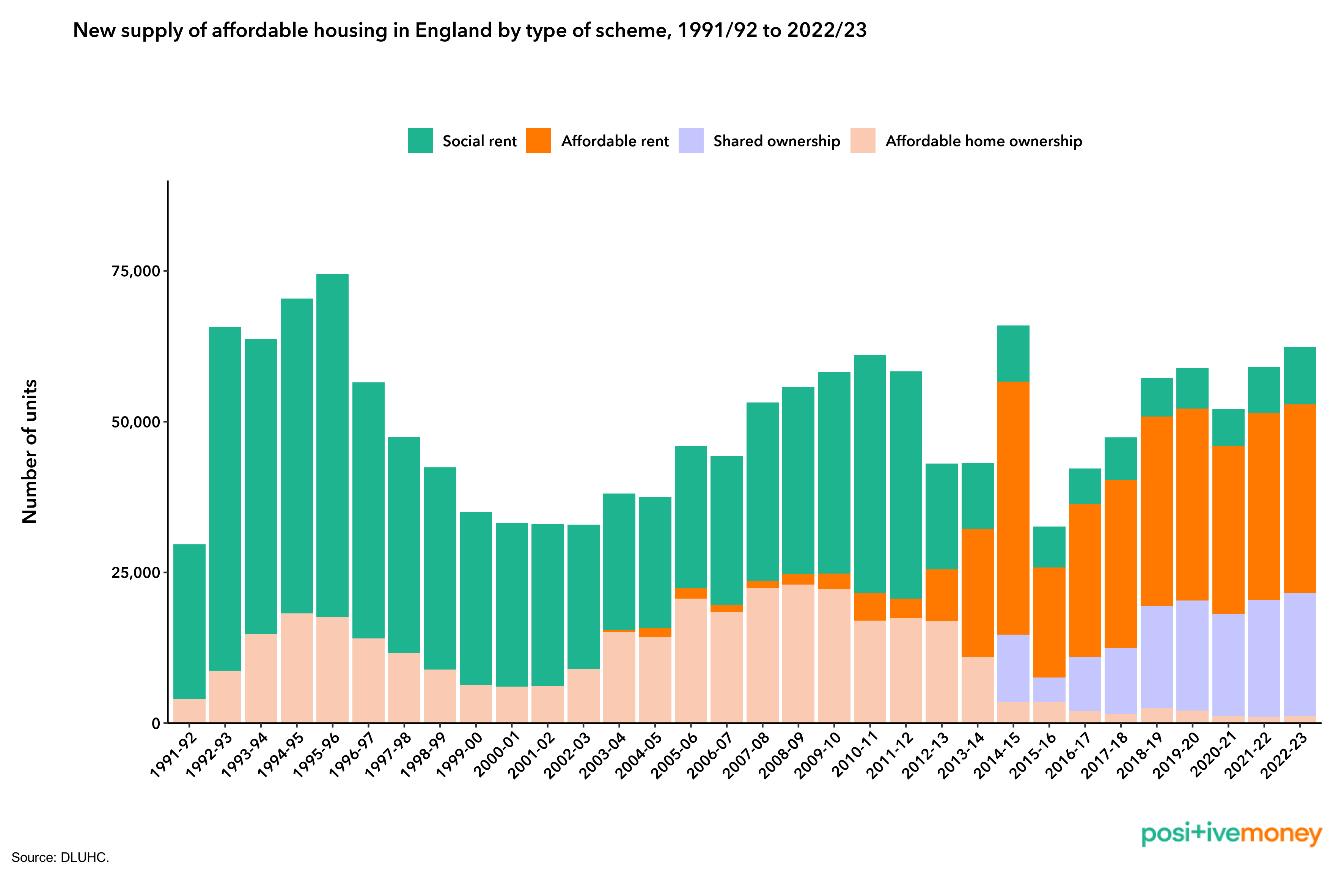

Annual new supply of social housing has for the past three decades only amounted to a fraction of that built between the 1950s and 1970s, when between 100,000 and 200,000 units were completed each year. Equally worrying is that the financialisation of housing has crept into social housing provision, with a growing share of ‘affordable housing’ being provided as shared ownership tenures.

Shared ownership is far too expensive for those most in need of affordable housing and comes with full responsibility for often unaffordable service charges without actual ownership rights. Combined with the risks of massive rent increases, shared ownership is clearly far from affordable and contributes to the financialisation of the housing market rather than tackles it.

Furthermore, the supply of affordable rent housing has almost completely replaced the supply of social rent units. Affordable rent is set at approximately 80% of market rent while social rent is set at around 50% of market rent, meaning that the supply of genuinely affordable housing has all but collapsed over the last decade, with less than 10,000 units of social rent supplied in England in 2022/23.

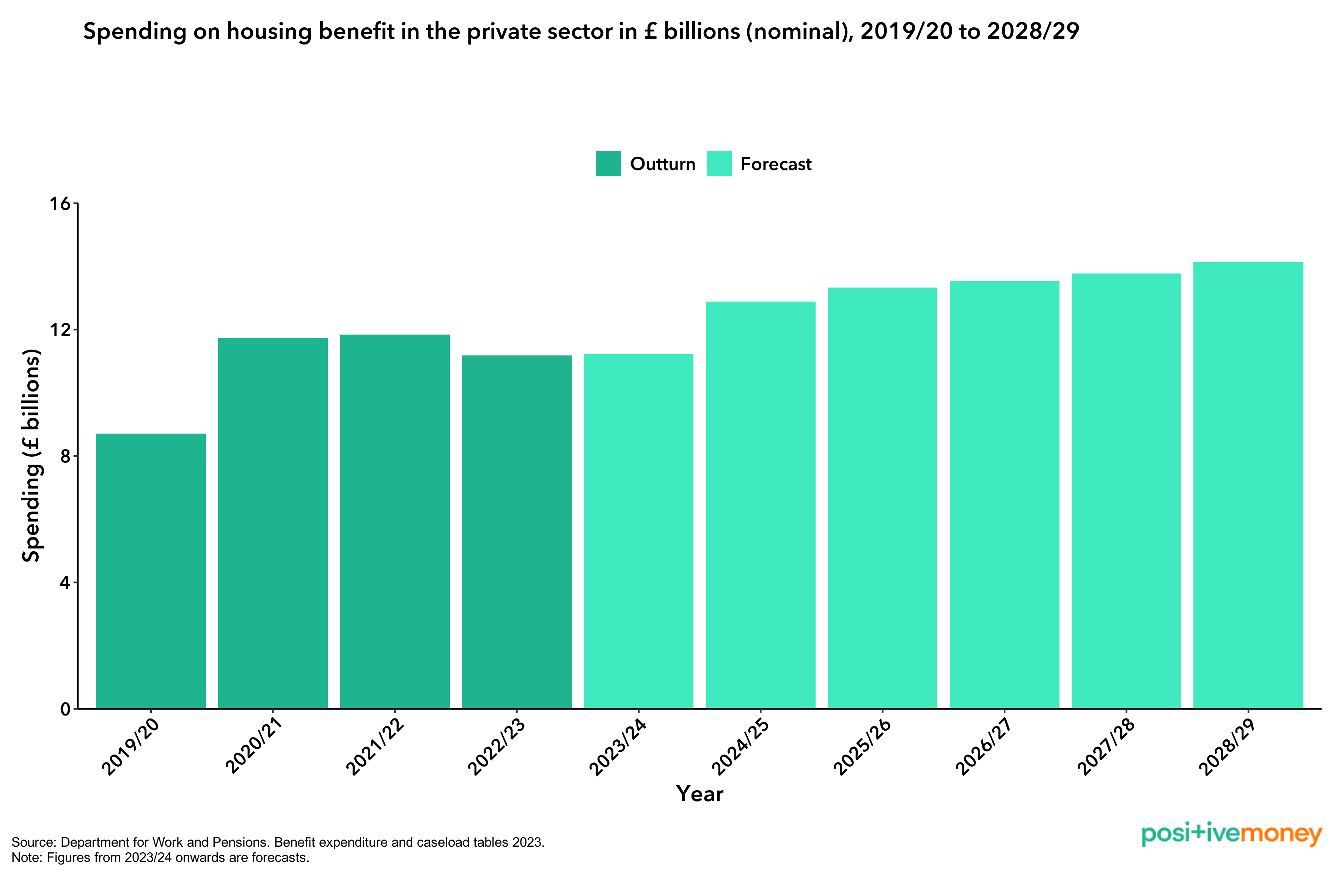

Instead of investing in the construction of genuinely affordable social housing, government housing expenditure has increasingly become a subsidy of the private rental market. A total of £8.7 billion was paid out in housing benefit to those living in the private rental market in 2019/20, but this figure is expected to rise to £14.1 billion by 2028/29 as an increasing number of those in receipt of housing benefits are forced to rent in the private sector due to the lack of social homes. These payments feed directly into the pockets of landlords and contribute to the inflation of already unaffordable rental prices.

At a time when landlords in Great Britain already collected £85.6 billion in rent from their tenants in 2023, forecasts show that the government will spend six times as much on subsidising private landlords than it does on building affordable housing between 2021 and 2026.

Renters have been particularly hard hit by the high interest rates set by the Bank of England, as landlords are able to pass on rising mortgage costs to their tenants in the form of higher rents. Almost half of private renters live in a home with a buy-to-let mortgage, showing how many renters are vulnerable to high interest rates.

Nevertheless, the Bank of England seems to have decided that renters are a good conduit for reducing demand and spending power in the economy, recognising that renters are more exposed to rate rises than mortgagors. Even if most of the inflation during recent years is primarily due to external forces, such as climate events, increased profit margins and volatility of energy markets rather than wage increases, the Bank appears happy to use interest rates to make renters even poorer than they already are in the hope of keeping inflation low.

Minutes from the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting on 31 July show that persistent elevated services inflation continues to cause concern among MPC members. However, since services inflation makes up 45% of the UK Consumer Price Index (CPI), and 17% of services inflation are rental costs, this can cause a feedback loop in which higher interest rates increase services inflation due to rising rental costs. Therefore, the desired effect on inflation is likely dampened by this feedback loop, even if renters certainly become poorer due to having to spend a larger proportion of income on rent.

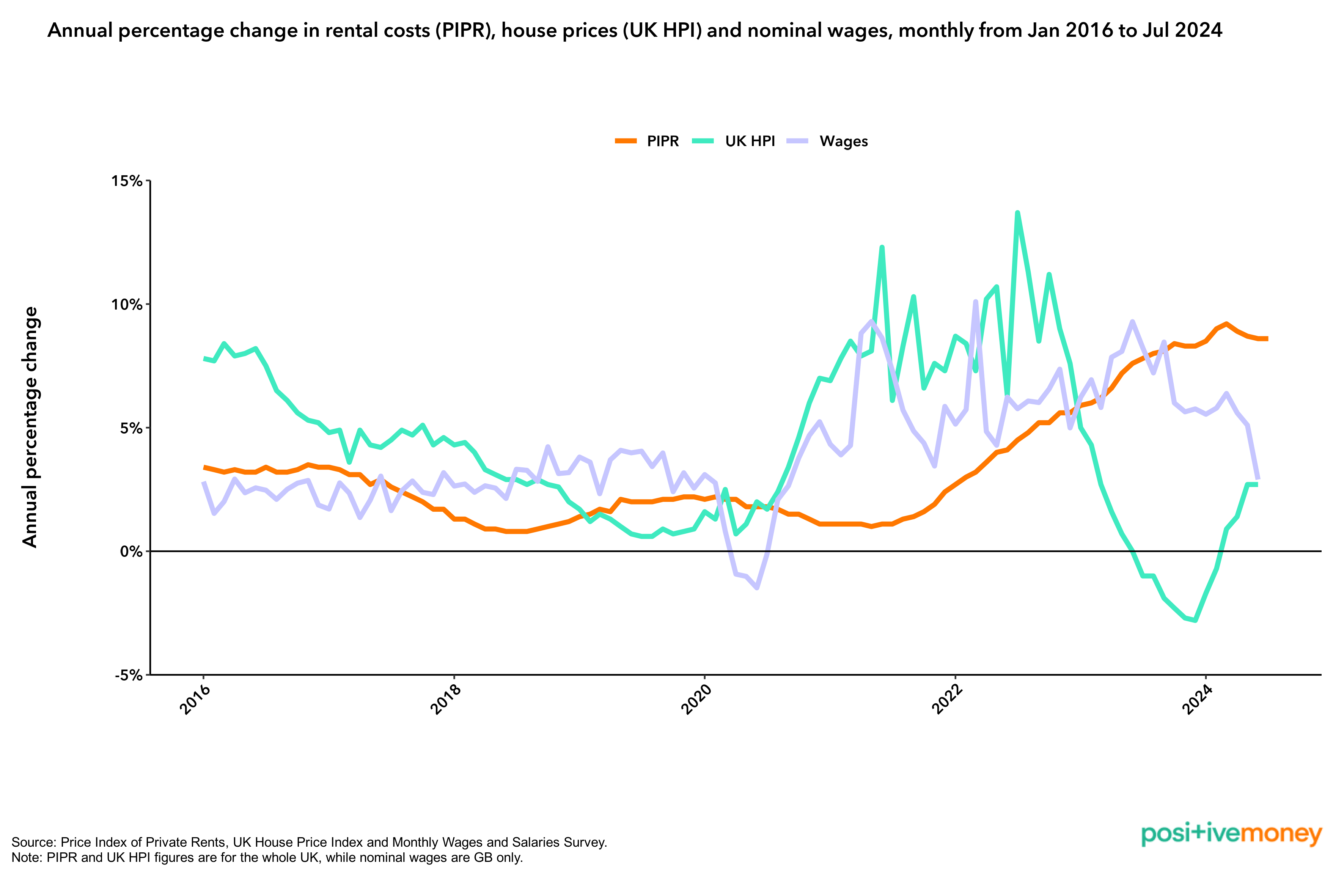

The effects of a largely unregulated, financialised private rental market combined with landlords passing on increased borrowing costs to their tenants has led to record-breaking increases in rental costs, rising by more than 8% year-on-year for each of the past 12 months.

Why should renters, who already face so many challenges, bear the additional burden of high interest rates after years of falling real wages? Why has government policy consistently favoured landlords and owner-occupiers over those who rent? Instead of hoping that increased supply will solve all housing problems, these are the questions we must ask if we are to develop a housing reform agenda that ensures everyone has the right to a secure and affordable home.

As Bank of England economists note, the reason why rents are so sensitive to interest hikes is precisely because properties function as assets. High interest rates used to mainly impact mortgage holders, but the fact that renters are now more vulnerable to the cost of debt than those benefiting from the credit is telling of whose interests the underlying macroeconomic framework and financial system serve.

Labour’s commitment to end unfair no-fault evictions and rental bidding wars are welcome, but their current housing plans offer little else for renters. The goal of the government’s focus on increasing supply seems to be more about boosting economic growth through the housing market rather than improving affordability, as even massively increased supply would do little to lower costs while consuming the entirety of our carbon budget. ‘Freedom to Buy’, Labour’s rebranded Conservative scheme meant to induce demand for mortgages, will help a select few buy a home at the cost of causing further inflationary pressure and worsening affordability for renters.

A long-term, holistic plan for tackling the rental and housing crisis is therefore necessary, but the government should also consider policies which can be implemented immediately to begin rebalancing the unequal power between renters and landlords.

One such option is rent controls, which the new government unfortunately has ruled out, at least for now. Rent controls are not a silver bullet to the affordability problem but would bring some immediate respite and have the added benefit of slowing down the rapid growth of house prices. Since the expected return on investment for landlords would decrease due to rent controls, buy-to-let landlords would not be willing to pay as much for properties.

This would help to definancialise the housing market as it would mean that more newly built homes would be owner-occupied rather than buy-to-lets, since owner-occupiers are not concerned about rental yields. The reduction in land costs and property prices would also make it more affordable for councils to acquire land for social housing development, or to simply buy private properties and turn them into social homes.

A large-scale programme to construct social homes and buy back privatised council homes must be part of the wider housing agenda, along with reducing financial and tax incentives for using homes as investment vehicles. Reforming property taxation into a progressive system that is proportional to the value of the property would also help to reduce the staggering 1.5 million unoccupied dwellings in England, as it would be less attractive to keep empty homes as investments.

The housing crisis in the UK is a crisis of affordability, inequality and financialisation. Renters, who are particularly vulnerable to its effects, cannot continue to be an afterthought in housing policy. The government must redefine its approach to housing policy by prioritising people over profit and placing renters at the centre of a radical reform agenda, guaranteeing a secure and affordable home for all.

-

Sign-up to our mailing list for regular updates, or donate to support our work to redesign our economic system for a better world and a healthy planet.