UKEU

18 February 2026

The dominance of the dollar grants the US significant leverage in global politics. It can use sanctions and tariffs to pressure and coerce other countries, or even confiscate their dollar assets, and it is employing these tools increasingly often.

Trump’s second term has marked a significant shift in US trade policy. Once a staunch defender and promoter of free trade and globalisation, the US is now applying (or threatening to apply) wide-ranging tariffs on various countries, including its neighbours and allies as well as geopolitical adversaries.

Using economic policy to apply pressure and coerce other countries is not a new strategy, as the US, UK, and EU have regularly applied economic sanctions on a range of countries in the Global South, with devastating consequences for the citizens of the sanctioned countries. However, the sheer scale of sanctions currently in place, and the increasing use of tariffs to exert diplomatic pressure, represent a significant increase in warfare by economic means.

But how is the US able to apply sanctions and use tariffs in this manner, and why can’t other countries do the same thing? It all has to do with the dominant role of the dollar in the International Monetary and Financial System (IMFS), which grants the US enormous power and leverage on the global stage.

The outsized role of the dollar in the global economic and financial system is not only beneficial to the US in terms of boosting the spending power and stability of its currency, but it can also be used to advance strategic, political or economic interests abroad. One way in which the dominance of the dollar bestows the US with significant leverage is through the ability to apply financial sanctions on other countries.

Financial sanctions most often take the form of trade restrictions in order to achieve a foreign policy goal. By prohibiting the trade of certain goods, or all trade, living standards among the population in the sanctioned country will generally fall and the citizens will suffer due to a lack of essential goods and services. The hope is that this will cause enough hardship among the people so that the leadership is forced to give in to the demands of the sanctioning country, or, alternatively, that the people will depose their leaders and establish a new leadership that is more aligned with the interests of the sanctioning country.

While it is theoretically possible for any country to impose such sanctions on another country, in reality it is primarily just the US that wields this economic weapon, even if its Global North allies often follow suit. The consequences of US sanctions are often devastating, precisely because of the dominance of the dollar and US control over the global payment infrastructure. If a small country, for example Nicaragua, would impose sanctions on the US or any other large economy, there would be little to no impact, as it does not control payment infrastructures, has a small role in global trade, and few entities use its currency.

However, because over half of global trade is facilitated using dollars, and payments in dollars go through the US-controlled SWIFT payment infrastructure and must be cleared through the US banking system, a sanction that is applied by the US has enormous repercussions. The sanctioned country cannot simply switch to trading with the same partners by using other currencies if alternative payment systems based on local currencies haven’t already been created. Furthermore, it can be difficult to find partners willing to trade with you even if such infrastructure does exist, since secondary sanctions would usually apply to any other entity that trades with the sanctioned country.

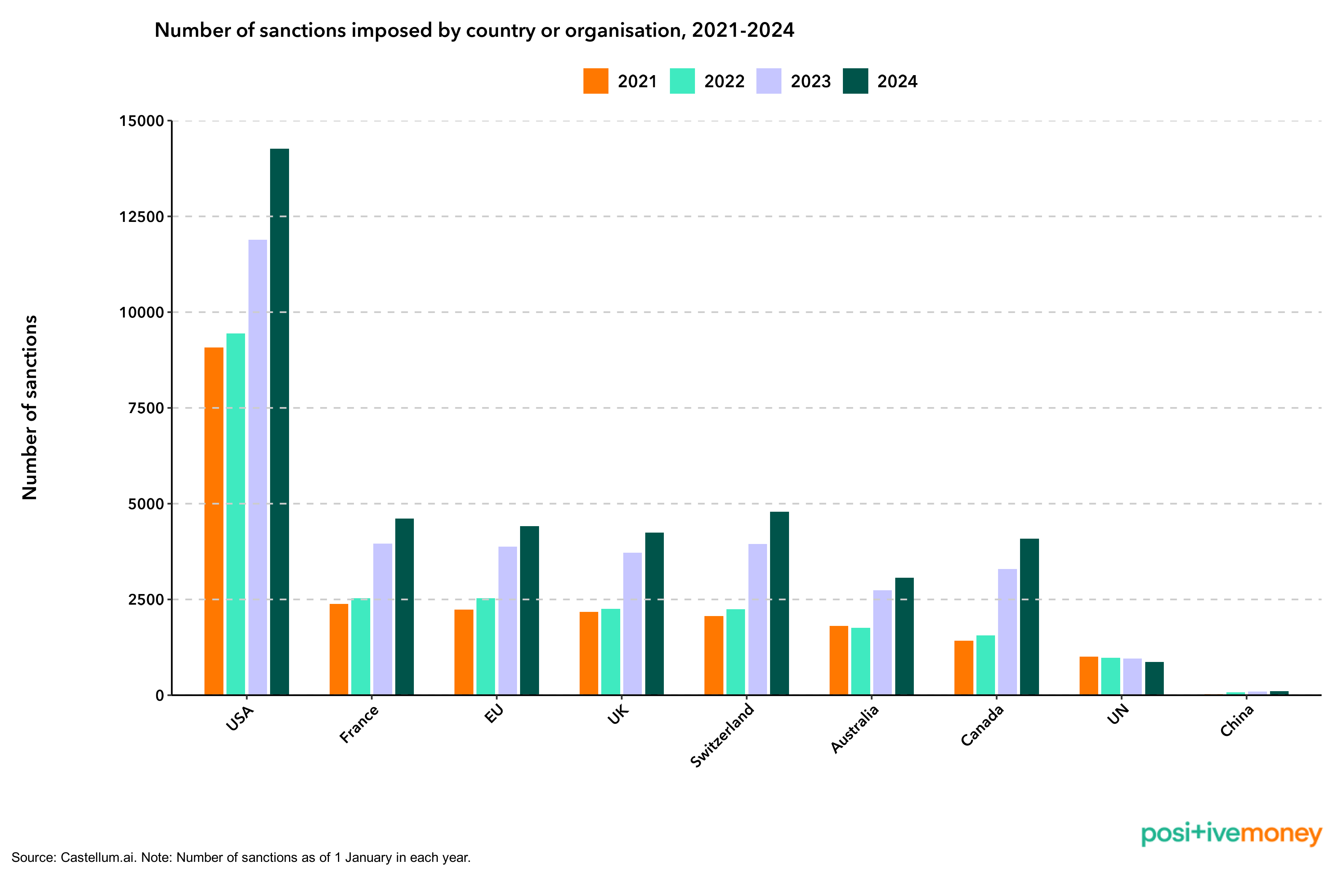

Essentially, because of the dominance of the dollar, the US has the ability to simply shut a whole country out of the global economy. The number of sanctions imposed by the US has increased drastically in the last few years, as can be seen in the graph below.

Another way in which the dominance of the dollar grants the US unique political leverage is through their ability to seize any dollar-denominated assets held by other countries or foreign entities.

Since the vast majority of money does not appear in physical form but rather as entries on a digital ledger, payment systems act as the plumbing of the IMFS by sharing information about how many dollars should be moved from one account to another. When commercial banks across the globe want to send dollars, they rely on the SWIFT financial messaging system to share information on how the ledger should be updated. This means that the participants in the dollar-based financial messaging system must adhere to US legal and technological frameworks, granting enormous power to the US and the Federal Reserve, as they are ultimately the only actors who can make changes to the ledger and decide who can participate in the financial messaging system.

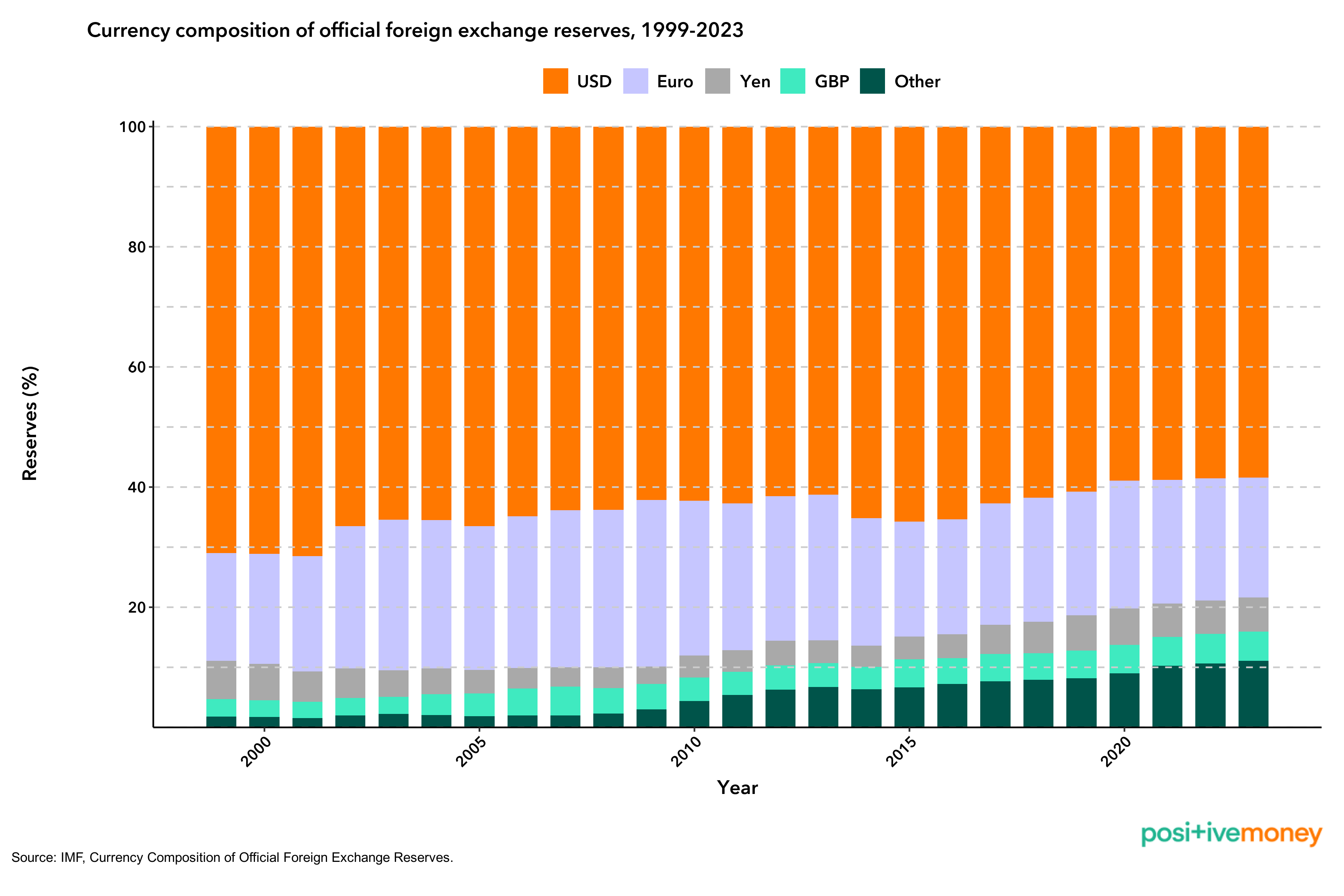

The US can decide to deny access to SWIFT, thereby making it impossible to move your dollars from one account to another, effectively seizing control of those assets. Given that dollars make up almost 60% of foreign reserves globally, this means that the US has the ability to confiscate or freeze close to two-thirds of global foreign exchange reserves.

As can be seen in the graph below, euros are the second-most held foreign reserve asset. While generally applying much fewer sanctions than the US, the EU recently took weaponisation of monetary policy one step further, by delivering interests derived from frozen Russian euro assets as monetary aid to Ukraine. Whilst the action could be considered justified given Russia’s invasion, the European Central Bank (ECB) and countries such as France and Germany worry that this weaponisation of monetary policy will result in lost confidence in the euro as a stable and secure asset.

Trade policy is closely intertwined with monetary policy, and the first months of the second Trump administration has shown how the US can use tariffs in an attempt to coerce other countries. Although tariffs can be imposed by any country, the dominance of the dollar makes US tariffs much more significant than those imposed by countries with smaller markets.

Given that many countries, particularly in the Global South, are highly dependent on accumulating dollars to pay for imports and to service foreign debt, the resulting loss of revenue in dollars following tariffs can wreak havoc on the economy. It may result in the inability to pay for necessary imports, or if it leads to a default on foreign debt then borrowing costs are likely to rise in the future, further reducing the economic sovereignty of dollar-dependent countries.

Trumps’ threat of imposing 100% tariffs on all BRICS nations attempting to de-dollarise their economies is an example of how trade policy can be used to threaten countries which aim to free themselves of the shackles of dollar dependency. Essentially, tariffs can be used by the US in an attempt to maintain the dominance of the dollar in the currency hierarchy, even if it will result in higher costs of living for workers in the US.

Although financial sanctions are a powerful weapon that the US has come to use more and more regularly, it is not entirely without repercussions.

It is precisely because the dollar has been viewed as a stable and safe currency that it has become so dominant on the international stage. An increasing weaponisation of the dollar (i.e. restricting access to the dollar-centric financial system or confiscating dollar assets) makes the dollar a much less attractive currency, as it then carries more risk to hold and therefore becomes less safe. The more the US applies financial sanctions, the more incentives it creates for others to reduce dependency on the dollar.

Down the road, this would also reduce the power of financial sanctions applied by the US as countries would be less dependent on the currency and related payment systems by having been forced to build alternative infrastructures to guard against sanctions, tariffs or other US policies.

This might have further implications for the US economy. If countries choose to implement strategies to reduce dollar dependency by building alternative financial infrastructures for trade and financing, this would also imply a lesser role for the US on the global stage. In addition, if fewer and fewer countries would use the dollar, then it would be more difficult for the US to finance its annual trade deficit by issuing more dollar-denominated debt. Instead, the US economy would either have to produce more domestically, or consume less from abroad.

Furthermore, sanctions do not always have the intended effect. For example, the unprecedented scale of sanctions on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine has done little to stop its war efforts. Instead it has resulted in trade between Russia and its major trade partners such as China and India to be almost completely de-dollarised, weakening the global power of the dollar. Oil trade has traditionally been conducted almost exclusively in dollars, but as a result of the sanctions only 80% of global oil trade was invoiced in dollars in 2023. Of course, Russia is a large country with a substantial industrial base and significant natural resources, so is much better positioned to adjust to sanctions than any smaller countries would be. Smaller countries, such as the island nation of Cuba which has endured a 63-year long trade embargo by the US, suffer much more under sanctions.

What is clear is that the dollar-centric global financial system grants the US enormous power to inflict pain and suffering on populations anywhere in the world to achieve their foreign policy goals without the use of military force, but with negative consequences that mirror those of armed conflicts. Currently over half of low-income nations have some form of US sanctions imposed on them.

The dominant role of the dollar is partly a result of the hegemonic status of the US, however, the dollar is also used as a tool to maintain that hegemony. The weaponisation of the dollar and monetary policy through economic sanctions are often used to tighten the grip over countries in the Global South, entrenching neo-colonial power dynamics and limiting economic sovereignty. Many Global South countries argue that an end to sanctions is necessary to break free from this cycle of dependency, however, without building alternative financial architecture that is less dependent on the dollar, sanctions are likely to continue to play a major role in US foreign policy.

Fortunately, however, there are ways in which countries can reduce susceptibility to the weaponisation of the dollar and US trade policy, as outlined in our recent ‘Beyond Dollar Dominance’ report. Among the most effective ways include building payment systems that use local currencies rather than the dollar or other Global North currencies. Not only would this ensure that payment system infrastructure is insulated from decisions made by the US, but it would also help to strengthen local currencies and boost intra-regional trade. Increasing development financing in local currencies by Global South-led multilateral development banks would also reduce exposure to decisions made in Washington by disentangling financing arrangements away from the dollar.

Combined with increased regional economic integration and trade, these policies would form the backbone of a new financial architecture that would increase economic sovereignty and guard against the ongoing weaponisation of the dollar.

Sign-up to our mailing list for regular updates, or donate to support our work to redesign our economic system for social justice and a liveable planet.