Green FinanceGlobal

1 December 2025

At the recent T20 Summit in Johannesburg, Senior Researcher Bruno De Conti spoke at the roundtable on “Digital Money: The G20's Next Financial Frontier”, which raised many interesting questions and shone a light on the need to reform our international monetary and financial system.

The G20, composed of the world's 19 richest countries and two regional bodies (the European Union and the African Union), is one of the most important forums for discussions in the global economy. As part of its activities, the G20 commissions the T20 - a selection of think tanks, research institutes and experts from G20 countries - to organise debates and make recommendations on critical topics. Invited by the T20 South Africa coordinators to participate in Taskforce 3 (Financing for Sustainable Development), in November I headed to Johannesburg in South Africa, to join the T20 Summit and make our calls for change clear.

At the roundtable session I participated in on ‘Digital Money: The G20's Next Financial Frontier’, the moderator, Paul Samson from the Centre for International Governance Innovation in Canada, raised the following question: “What could a credible global framework for digital money governance look like?” Here is my response.

The International Monetary and Financial System (IMFS) is undergoing crucial transformations. Not by chance, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) indicates that we are living a “money revolution”. As a consequence, we need serious discussions about the governance of this new IMFS. We understand that there are three key pillars for this governance:

1) Public Money should be at the core of the system

It means that: i) monetary authorities all over the world should create their own Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs); ii) private money, and private financial assets should be strictly regulated.

Around 70 countries are currently developing their CBDCs. Yet, it is important to highlight that there are significant changes and very strong tensions in this sphere since the beginning of the year. After all, Donald Trump, on the fourth day of his second mandate as the president of the USA released a White House order forbidding the development of a digital dollar, and making very clear his choice to move ahead in the process of currency digitalisation through private assets, like cryptocurrencies, instead of CBDCs. Given the structural power of the USA - ie, the power to reshape the system structures - Trump's decision has important implications over the whole globe.

Since then, many other countries in the world have stepped down or are at least hesitating in their processes of developing a CBDC. South Korea paused the project, there are rumours in the UK that the digital pound project may be abandoned, and in the Eurozone, Fernando Navarrete has recently released a report defending private solutions for pan-European payments and an offline CBDC, in a clear attempt to kill the digital euro project.

It is very important that monetary authorities in the whole world proceed with the development of their CBDCs. Public and private money coexist, and have always coexisted. Public money, private money and private crypto assets coexist, and will coexist. But it is crucial to have public money in the digital form as an alternative, at the heart of the new system. At the same time, it is imperative to have strong regulation of the operations of private actors worldwide in this domain. Not to create a monopoly and curb competition, but precisely the opposite: to face the oligopolies that currently characterise the financial system - and we can imagine what may happen when the giant techs (e.g. X, Amazon, Google) enter more profoundly in this market. Their market power will certainly not lead to public welfare, so this market has to be strictly regulated.

Moreover, it’s also important to stress that the strong regulation should not be aimed at curbing innovation from the private sector, but rather to avoid that innovation in a deregulated system leads to speculation, and to a deep crisis. The amount of crypto assets in the world is estimated today at almost US$ 4 trillion; stablecoins alone, for almost US$ 300 million. This market should be strongly regulated, otherwise it may lead to a deep financial crisis.

2) Reducing the asymmetries of the current IMFS

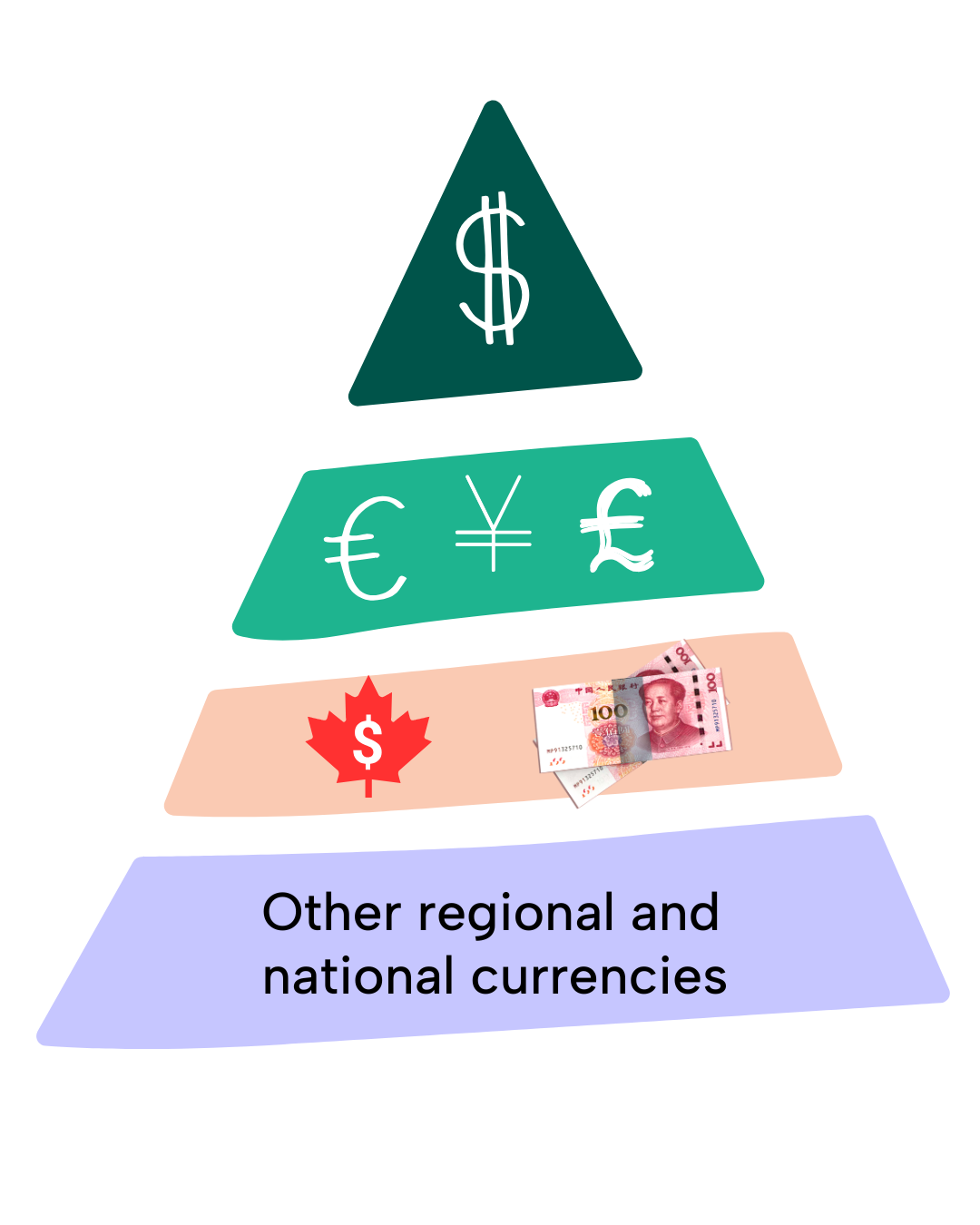

The current IMFS is completely asymmetric and unjust. It reflects a world that does not exist anymore, and not at all the world that we should aspire to for the future.

The current hegemony of the dollar - or dollar dominance - results in an “exorbitant privilege" to the USA, and in very important problems to the rest of the world, especially for the Global South: high interest rates, high exchange rate volatility, the burden of external debts in US$, balance of payment crisis leading to a lack of dollars that may hinders crucial investments (for instance, those related to the green transition) - for a deep discussion on the negative effects of the dollar hegemony, see our report Beyond Dollar Dominance.

It is therefore frustrating to see that most reports from Global North Central Banks and from multilateral institutions, even if they are in favour of CBDCs, are restricted to a motto which is “faster, cheaper and more transparent” payments. This is all quite important, but it is crucial to use this opportunity also to reshape the IMFS in the direction of a more symmetric system, less dependent on the US dollar and reflecting the transition into a multipolar world. This was highlighted in the T20 Final Communiqué, which included our recommendation for efforts aimed at building a multi-currency International Financial Architecture (IFA). This includes support for the development of multi-currency cross-border payment systems, and the transition into CBDCs should have it as an essential principle.

3) Avoiding technological dependence

The transition into digital currencies may create an additional risk for Global South countries, which comes from increasing technological dependency. For the development and operation of CBDCs, there are several technological layers, and some of them are particularly crucial for the sovereignty of a country. In simple terms, we are talking about the place where the CBDC system will be hosted, the softwares that will be used, etc. A counter-example comes from the D-Cash, that is being developed by the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU): according to Schumacher (2024), the storage system will be Google Cloud. If it happens, it will certainly mean a strong vulnerability and a big threat for the monetary sovereignty of these countries. Hence, the global governance on CBDCs should deal with this serious problem, avoiding that Global South countries fall into a higher technological dependency on the Global North.

Assuring sovereignty and combating monetary and financial asymmetries

History shows that in moments of important transformations in the system – in this case, in the IMFS – there is a race of the most powerful countries in the world to set the new standards. Specifically, to set the new global standards in the technological sphere, and in the sphere of regulation, to benefit their own interests. This race is happening now (De Conti and Guttmann, 2025). We should avoid that these new standards are set by any isolated country or only by the Global North. Global South countries should be part of this process. The system we aspire to is a system which respects monetary sovereignty at the national level; and reduces the asymmetries of the system at the international level. This is a gigantic challenge, but absolutely necessary for the construction of a just IMFS.

Sign-up to our mailing list for regular updates, or donate to support our work to redesign our economic system for social justice and a liveable planet.