The ultimate magic money tree has been unveiled – don’t let the government tell you otherwise

Despite the extension of the Ways and Means facility and expanded Quantitative Easing, the Treasury and the Bank of England might still deny that they are engaged in monetary financing and attempt to justify a return to austerity. We can’t let that happen.

On 9th April, HM Treasury and the Bank of England jointly announced an open-ended extension of the Ways and Means facility – the government’s overdraft at the central bank – further increasing the level of coordination between the two institutions. While the move is intended to smooth the government’s cashflows and facilitate the market’s absorption of bonds, it is in effect a form of direct monetary financing. To guide discussion and what is and what is not monetary financing, we recommend this paper by van Lerven and Ryan-Collins, which provides the following typology:

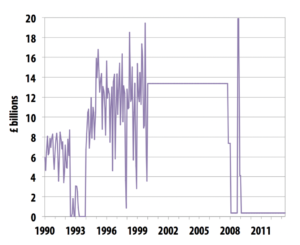

The Ways and Means facility – which falls under 2b in the table above – used to be a standard part of the monetary policy toolkit in the UK. It was protected in EU negotiations, resulting in its exemption from Article 123 of the governing treaty, which otherwise prohibits direct monetary financing. Nonetheless, in 2000 the facility was frozen at £13.37 billion before being paid down to £370 million in 2008, where it has since remained barring a brief moment during the 2008 crisis when it hit £20 billion.

Source: Jackson and Dyson, 2013 (based on ONS data)

Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey had previously ruled out monetary financing as a policy option, even though an indirect form was already happening through the Bank’s Quantitative Easing (QE) programme: as the Treasury increases its deficit spending, the Bank issues newly-created money in exchange for government debt, none of which has ever been sold back to the market. As long as these bonds stay on the Bank’s balance sheet, they represent money that the government owes to itself. As of yet, neither the Bank nor the Treasury have recognised this arrangement for what it is.

The Treasury and the Bank might now also deny that the extension of the Ways and Means facility represents any kind of monetary financing, on the basis that it is temporary and “any drawings will be repaid as soon as possible before the end of the year.” What the Treasury won’t highlight is that if it does pay back its overdraft, the debt issued to raise the money for the repayment may well be bought by the Bank through its QE programme anyway, and kept on its balance sheet for the foreseeable future.

This would amount to the following 3-step sequence of events: (i) the Bank creates money injected into the economy via the Treasury’s use of the Ways and Means facility; (ii) the Treasury extracts (i.e. destroys) money from the economy by selling bonds to repay its drawings from the facility; (iii) the Bank creates new money again through its purchase of the bonds that were issued by the Treasury to repay the Bank.

Ultimately, net creation of money would remain the same, as would the government’s consolidated (Treasury + Bank of England) balance sheet. Assuming continued high demand for government debt, there would also be little practical difference to the government’s financing conditions.

Therefore, in the context of ongoing QE, fervently emphasising that drawings from the Ways and Means facility will be repaid as soon as possible represents a thinly-veiled attempt to uphold the myth that the Bank cannot sustainably finance the Treasury. In other words, the government may be trying to keep the door open for a return of the “no magic money tree” line and associated austerity discourse, which is already creeping back into view.

However, even if the Treasury insists on repaying the overdraft, its extension still shows the public that government spending need not depend solely on taxation and the bond market, and adds to the already strong case against austerity. The public can now see for itself that the Bank is able to finance the Treasury’s spending in the most direct of manners without any strict limit. Rapid repayment and freezing of the overdraft would be a purely political choice, which we would deem difficult to justify.

Keeping the Ways and Means facility open for flexible use would have clear benefits. In particular, it would ensure that the government is always able to spend without relying on debt markets, which may not offer such favourable financing conditions indefinitely. Further, this kind of direct monetary financing undermines the case for using ineffective conventional QE – with all its negative side-effects – to stimulate the economy as we emerge from lockdown. Lastly, as things stand we see little reason to worry about runaway inflation, which we will discuss further in a forthcoming post.

The ultimate magic money tree has been unveiled, whether the government is ready to admit it or not. This provides excellent fodder for debunking myths about money and finance as we emerge from the current crisis. It is now essential that we use it to fight back against the return of austerity.