Bank of England finally admits high house prices are determined by finance, not supply and demand

The Bank of England confirms Positive Money analysis of housing affordability

In a duo of fascinating blog posts this month, Bank of England researchers John Lewis and Fergus Cumming confirmed what we’ve been arguing for a long time: that houses are assets, the price of which is not determined so much by simple textbook supply and demand as with typical consumer goods, but by the role of finance.

The mainstream narrative on Britain’s housing crisis is that housing is so expensive because there are simply not enough homes to go around. As I have argued elsewhere, not only is this narrative misleading, but it serves the pockets of property developers, and lets the real culprits – bankers and landlords – off the hook.

Unfortunately, even the Bank of England has fallen into this habit at times, with governor Mark Carney repeating statements such as “The underlying dynamic reflects a chronic shortage of housing supply, which the Bank can’t tackle directly.”

But research from the Bank of England’s own staff suggests Carney should have known better – and perhaps that the Bank itself has been complicit in pushing house prices out of reach. In ‘Houses are assets not goods: taking the theory to the UK data’, Lewis and Cumming construct a twenty year model which shows that “relative scarcity of housing has played almost no role at the national level since 2000” in rocketing prices.

Rather, the Bank’s researchers confirm our view that high house prices are driven by the role of finance. In particular, they identify the role of the central bank’s own monetary policy (i.e. historically low interest rates) in driving up house prices.

As Lewis and Cumming explain, lower interest rates increase the value of future income flows from an asset and thus the amount people are willing to pay to own it (or more accurately in the case of housing, how much banks are willing to lend), as well as borrowers’ ability to take on more debt. This incentivises banks to lend more and more people to borrow. They suggest that lower interest rates, which have been pushed onto a downward trajectory by the Bank of England since the early 1990s, account “for almost all real house price rises since 2000.”

The price rises are striking. In the 1930s a typical three bed house was just 1 and a half times the average annual salary. By 1997 the average house price was 3.6 times the average salary. But in just twenty years that has more than doubled to nearly 8 times, and in London an ‘affordable’ home is 13 times first-time buyers’ salaries.

But there is another crucial element which is somewhat absent from Lewis and Cumming’s blogs – the role of banks in driving demand for housing as an asset.

As Positive Money has raised awareness of, banks do not simply lend out existing savings. Rather banks create new money when they make loans, which means they aren’t constrained in how much they’re able to lend by depositors’ existing savings. Banks then use this ability to create money to bid up the price of profitable assets like property. With over half of new money in the UK going towards mortgage lending, it’s no surprise that house prices have ballooned out of step with the rest of the economy.

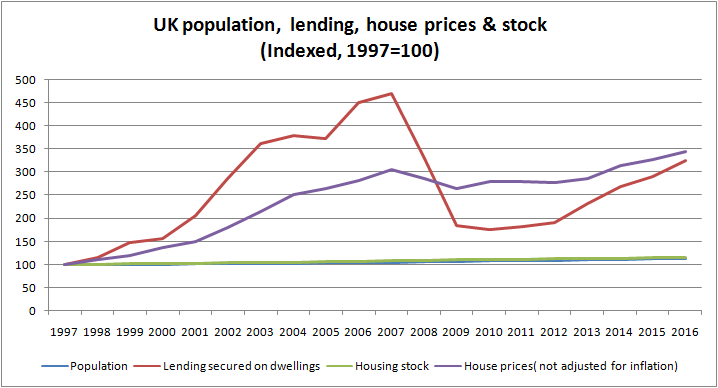

If we look at the data, the shortage myth becomes clear. Housing stock levels have consistently risen at a higher rate than population growth even in the past couple of decades, and even in London. So, according to the laws of supply and demand, if houses were a simple consumer good, prices should have fallen – obviously not the case.

The key relationship to look at is not the one between housing stock and house prices, but rather between lending towards mortgages and house prices, as the below graph illustrates.

Source: Positive Money (using Nationwide housing survey and Bank of England data).

This phenomenon was covered by founding Positive Money researchers Andrew Jackson and Ben Dyson in Modernising Money back in 2012 as well as elsewhere on our website. It’s great to see the Bank of England catching up!

The laissez-faire approach from policymakers since 1971 – dismantling credit controls, letting more lenders get involved in mortgages and changing the role of building societies, to name a few deregulations – has helped to create a booming market for housing speculation, which has been great for the asset-wealthy few, but not so much for the rest of us. And as Lewis and Cumming make clear, the Bank of England has played a central role in this, by continually cutting interest rates to keep the asset price party going, making property seem a one way bet.

We’re glad the Bank of England is finally acknowledging the impact of its policies. But the fact that central bankers were able to neglect these considerations for so long reflects the need to reconsider the Bank of England’s targets and tools, so that such impacts on larger, asset poor parts, of the population can no longer be overlooked.