Have rising house prices reached their limit?

UK house prices are “stagnating”, having declined in the last three months; it’s the first quarterly fall since being on the cusp of the double-dip recession in 2012.

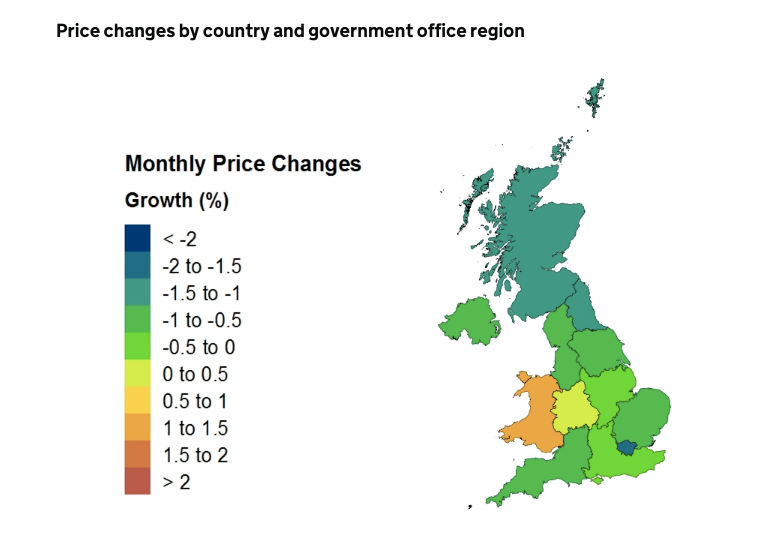

According to statistics provided by the ONS today, house prices in April declined by 0.6% compared to the previous month. Data from Halifax showed a similar picture, with prices falling 0.2% in the three months leading to April. This is the first time that there have been three consecutive months of house price decline since the economy was stuttering back in November 2012.

What’s behind this slowdown in the UK property market? Larry Elliot of the Guardian notes, home ownership is still a priority for most people. Whether it’s because people want their own home, they are simply afraid of eventually being priced out of the property market altogether, or because buying has become cheaper than renting – there is no shortage of domestic demand.

On the other hand, Elliot notes that interest rates are at an historic low. This means that it has never been cheaper to borrow to buy a house. But it also means that the returns on traditional savings vehicles are down, and investing in property is the logical ‘next best’ alternative – as the Bank of England’s chief economist Andy Haldane recently conceded.

Meanwhile, the Bank of England has recently acquired another £70 billion worth of traditionally safe investments (largely in the form of government bonds) in exchange for the newly-created money. This inflates the price of financial assets and pushes up property prices as well.

Finally, the weakened pound means that property in the UK might be a more attractive investment than ever for overseas buyers.

But why then are property prices showing signs of stagnation – or at least not booming at the rate to which we have become accustomed? It’s clearly not due to a lack of demand, is it?

A logical reason might be that the Brexit vote is putting off investment. Similarly, the rising costs of living associated with Brexit might be taking its toll, putting potential house-buyers off.

An argument can be made that neither seems entirely convincing, as Elliot writes:

“Robust car sales suggest consumers are happy to buy big-ticket items, while the recent rise in the cost of living has been modest by historic standards. Inflation stands at just over 2%; within the past half decade, it has been above 5%.”

This analysis seems sensible, but it’s worth remembering that company purchases account for a large chunk of car sales, and the rise isn’t necessarily reflective of households feeling more comfortable making big purchases. In addition, it’s possible that the Brexit vote may have put buyers in a more confident position to negotiate a better price, with vendors feeling conversely less positive.

Larry Elliot concludes that:

“The likeliest explanation for the muted state of the property market is that houses are simply too expensive for first-time buyers, even with mortgage rates as low as they are…There was a limit to how far house prices could rise and that limit has been reached.”

Martin Ellis, Halifax housing economist, said:

“Housing demand appears to have been curbed in recent months due to the deterioration in housing affordability caused by a sustained period of rapid house price growth…”

The UK property market is complex and multi-faceted. It has defied the expectations and forecasts of the best and most experienced economists. So everything should be taken with a pinch of salt, and nothing is set in stone.

But to a large extent, there seems to be good reason to believe that UK house prices have simply gotten too expensive – that people can no longer afford to buy them.