EUUK

3 July 2025

Christine Lagarde has recently argued that the price stability and financial stability objectives of the European Central Bank (ECB) are not at odds with one another. While in tranquil times this assertion may be true, it does not apply in the current context. Higher rates create turmoil in the financial markets, jeopardising the financial stability objective.

Just after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Lagarde declared, during the last Governing Council press conference, that there is no trade-off between the ECB’s price stability and financial stability objectives. She reiterated that same point later in the monetary dialogue, just after the downfall of Credit Suisse, and once again in the ECB’s watchers conference. It is thus safe to say that she seems quite sure about it.

The transmission of monetary policy is a convoluted subject. While the exact way in which higher rates impact inflation is a highly debated topic in academic circles, one thing is certain: central banks impact inflation by influencing financial conditions. The effect of higher interest rates on financial conditions is direct, while that on inflation is rather blurry. When aiming to reduce inflation, before interest rates can target the objective of price stability, they have to negatively impact financial stability.

It is rather surprising that just a few days after the SVB collapse, Lagarde came up with such a strong statement. It is puzzling because SVB’s downfall is partly explained by the impact of the Fed’s rate hikes, to which one has to add flagrant mismanagement and a very run-prone depositor base.

SVB had a portfolio of $120 billion in long-term securities — mostly government bonds and mortgage-backed securities — on the asset side of its balance sheet. When rates rise, the price of securities, especially long-term ones, declines. Owners of bonds receive fixed interest payments, so, if the market rate of interest increases, and bondholders want to sell their bonds, they need to sell them at a lower price so that the return on their investment reflects this new rate. Otherwise, no one would be interested in buying a bond that offers lower returns. This is what we call interest rate risk: the risk that changes in interest rates pose to financial asset prices.

As its depositors withdrew their deposits, SVB had to sell some of its securities at a loss. Once the news got around, and considering that a high share of its depositor base was uninsured, it triggered the oldest of problems in banking: a bank run. While there are very particular idiosyncrasies to SVB, there is a clear link running from interest rate hikes to its eventual downfall [1].

Quantitative easing policies, namely buying banks’ long-term securities in return for short-term reserves with variable interest rates, have partly cushioned European banks from interest rate risks. Yet, non-bank financial institutions that hold large chunks of long-term financial assets are still exposed to interest rate risks, and banks’ exposure to them will be exacerbated as quantitative tightening increases its pace.

Another important risk that rate hikes can trigger is credit risk. This type of risk occurs when borrowers are unable to meet their payment commitments.

The larger the share of economic agents that are in financial distress, meaning that their cash inflows do not suffice to face their payment commitments, the more that the financial system is unstable [2]. Tighter monetary policy, by increasing interest payments, decreasing incomes and reducing the volume of loans, increases the degree of financial stress in the economy.

Let’s illustrate this with a couple of examples. If I’m a household with an adjustable interest rate, I will experience a substantial increase in my interest payments as rates rise. Moreover, suppose my income is negatively affected by the economic downturn that central banks aim to bring about with a tighter policy stance. In this case, the simultaneous increase in my payment commitments and decrease in cash inflows can push me from a healthy financial situation to not being able to make my payment commitments.

As the tightening of monetary policy worsens economic conditions and future expectations, banks become more risk averse. This means that they constrain their credit standards, as well as their terms and conditions when providing loans [3]. This eventually leads to a higher probability of them not considering the debtor creditworthy, and hence, not handing over the loan. If a firm whose repayment of principal was due this year was thinking of rolling it over, the extreme case of not being able to do so due to higher constraints to borrowing may leave the firm in a dire situation. These situations can trigger fire sales, which further increase turbulence.

The increase in credit risks leads to solvency issues, which in turn leads to bankruptcies. In contrast to liquidity drying up, the ECB can’t do much about this. Paul Volcker — ex-chairman of the Federal Reserve — argued that monetary policy brings inflation down through bankruptcies. So far, the ECB has not been particularly “successful” on that front. However, as interest rates continue to rise, we should be wary of the tension that they create.

In tranquil times, enforcing strict financial regulation, which ensures that the financial system is resilient, is not at odds with price stability. The enforcement of financial regulatory policies in the post-Global Financial Crisis period is an example of this.

Yet, this was not what Lagarde was referring to when arguing about the inexistence of the trade-off. Rather, she argued that if stress was triggered in financial markets, the ECB can use existing or new facilities to provide liquidity in order to calm the market. This framing is quite confusing, as there is an implicit recognition that interest rates can jeopardise financial stability. Counteracting these effects with other instruments does not mean that there is no trade-off. Rather, it would amount to the ECB saying “let’s tighten financial conditions” with one instrument, while it responds “wait, not like that!” with the other. It essentially amounts to accepting that the trade-off exists, and arguing that financial stability needs to take precedence when they clash.

Lagarde’s framing also side steps the fact that rising rates can create solvency issues, to which the ECB can’t act, and that panics in the financial market can arise extremely quickly and leave long strains if the ECB is not quick enough in its response.

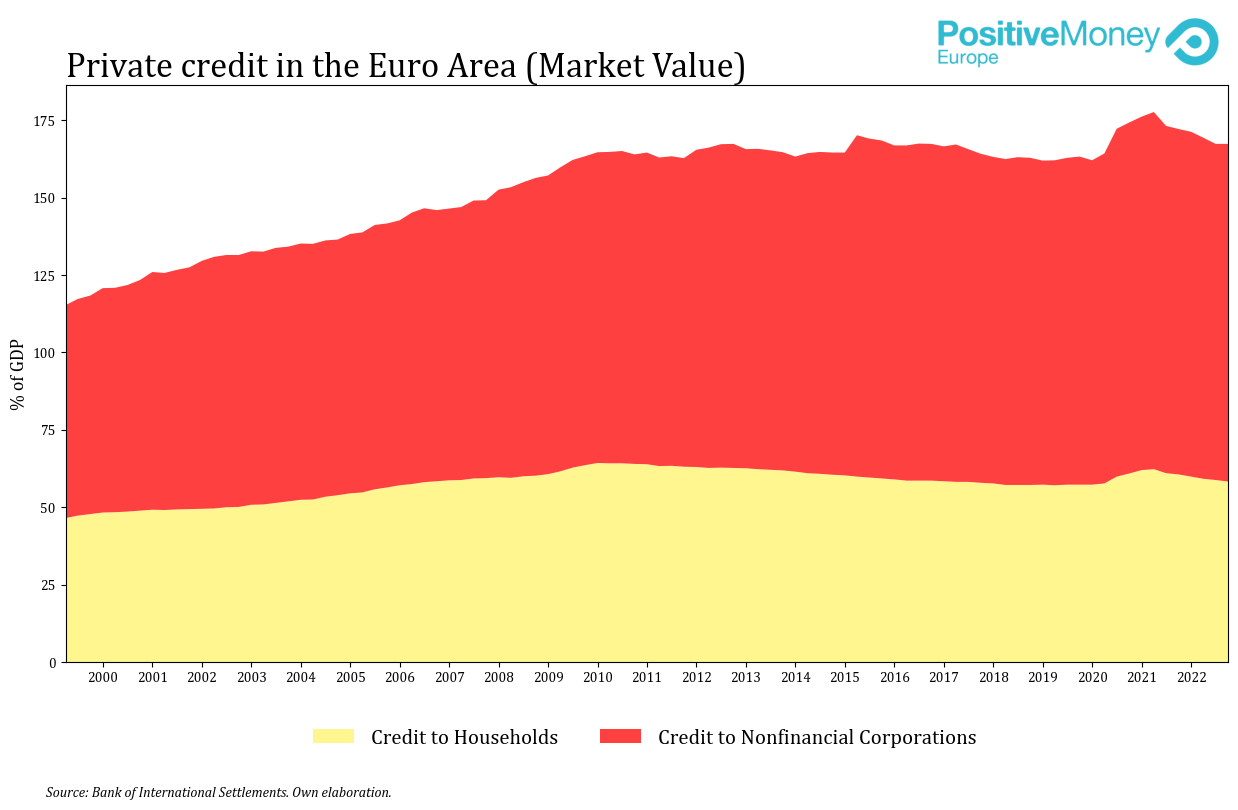

In a recent study, economists from the Bank of International Settlements looked at more than a hundred tightening events in a large sample of countries, finding that rate hikes increase the probability of triggering financial stress, especially when the ratio of private credit-to-GDP is high. This means that during tranquil times, a tight financial regulation which limits the accumulation of private debt is consistent with price stability. Yet, once you’re already increasing rates, it is too late to decide on what financial conditions you’re tightening on.

As we can see in the figure below, private debt in the euro area — even if slightly reduced during the Covid crisis — is very high. In fact, it is higher than in the years prior to the Global Financial Crisis. This should be raising some alarms at the ECB’s headquarters.

There are good reasons to believe that the financial system is relatively more resilient than in the past due to a strong labour market (against some ECB officials’ desires), a more solid financial regulation and the legacy of quantitative easing programmes in banks’ balance sheets. For these reasons, the current rate hikes may not result in a financial crisis.

However, it is simply not true that there is no trade-off between price stability and financial stability. The current ECB strategy of pumping up interest rates brings us closer to a financial crisis, and, to that extent, the trade-off exists in the present context. If the ECB tightens too much, things will break. With all eyes on the commercial real estate market, Lagarde should wage her words more carefully, as they may come back to haunt her.

[1] For a more in-depth analysis of SVB, see Banks as Hedge Funds by Elham Saeidinezhad, Silicon Valley Bank by Daniel H. Neilson and Misdiagnosing SVB by Steven Kelly.

[2] This argument is a simplification of the Financial Instability Hypothesis, by Hyman Minsky.

[3] The latest Banking Lending Survey for the last quarter of 2022 pointed to a tightening of banks’ credit standards, and the terms and conditions of loans. It also highlighted that the rejection rate of loan applications increased.