MacroeconomicsUK

15 October 2025

New data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) has estimated that the value of our homes continued to boom during the second year of the pandemic. But despite this increase, COVID-19 still saw people fall into fuel poverty, homelessness and poor quality homes. We take a look at who gains when the price of our homes increases, and how we could build a system that does a better job of bringing this value back to our pockets and communities.

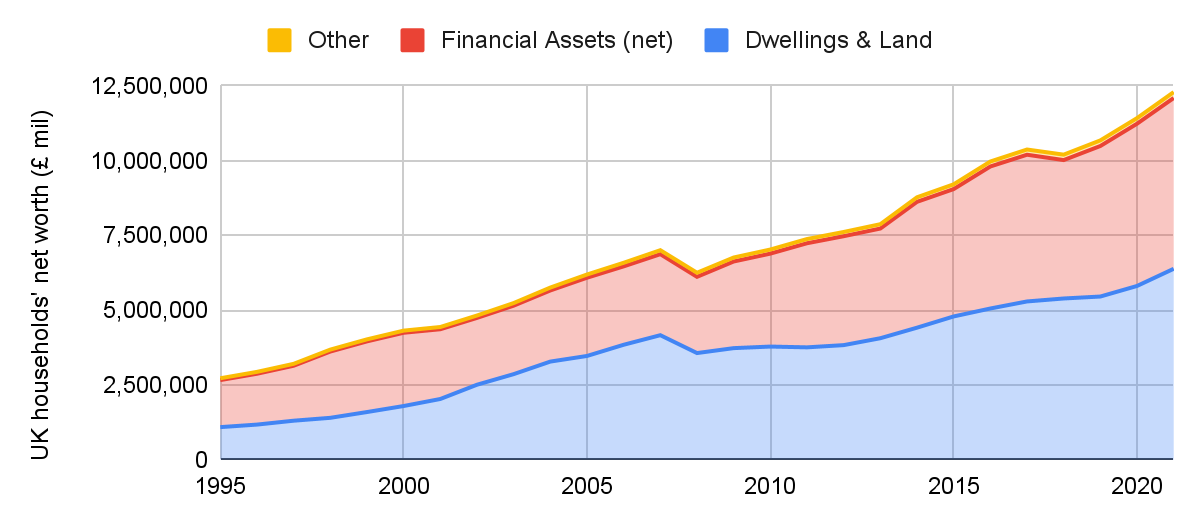

Every year, the ONS measures the ‘wealth’ held by UK households, including their cash in savings, the value of any land and property they own, and their pensions, insurance and other investments. The latest data, released last month, estimated the total amount of wealth held by UK households to have grown by £900 billion in 2021, to £12.3 trillion (Figure 1).

Figure 1: UK households’ net worth 1995-2021. This shows that UK households’ total wealth continued to increase during the pandemic: by 7.6% in 2021, and 7.0% in 2020. The value of land and dwellings is about half (52%) of household wealth. Most of the remainder are financial assets, including loans, insurance, pensions and other investments. Source: ONS, 2023.

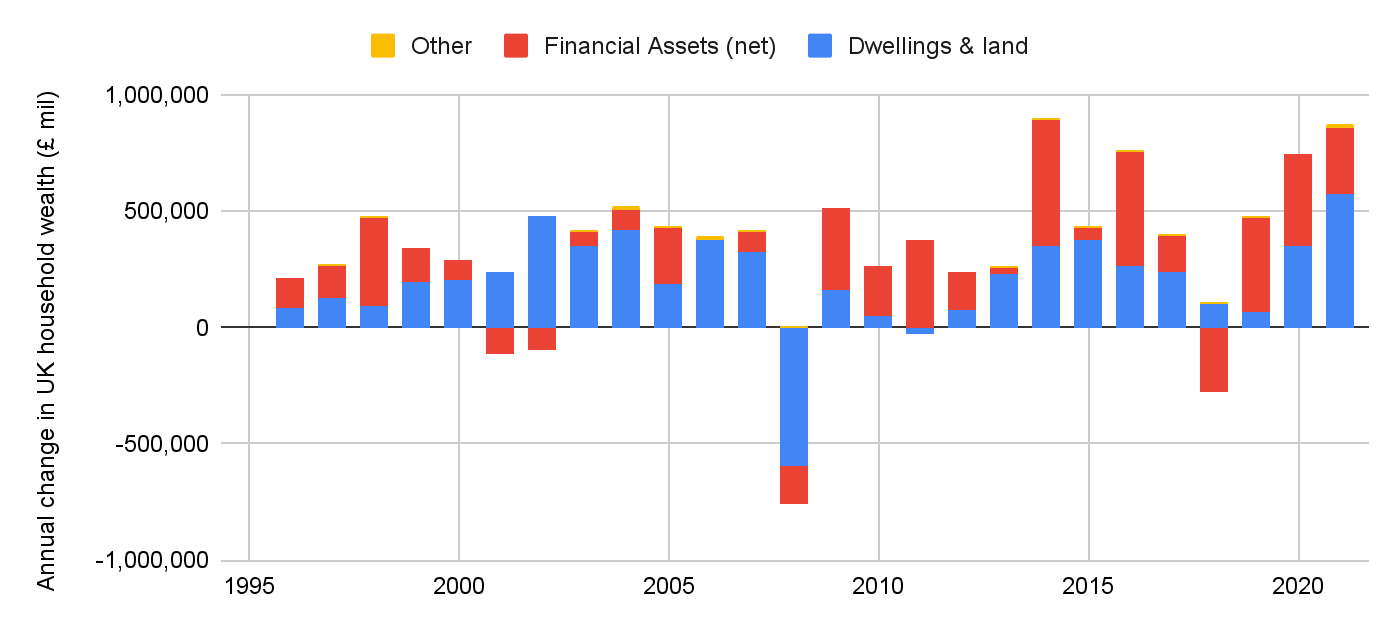

Despite the ongoing pandemic, this was an increase of 7.6%, the largest annual growth in the record since 2016, and the second largest since at least 1996 (Figure 2). The ONS measurements also recorded significant wealth increases in 2020, the first year of the pandemic, estimating that household net wealth grew 7.0% (£0.57 trillion) to £11.4 trillion. Both years showed around double the recorded annual average increases (3.3%) in household wealth since the 2008 crash.

Figure 2: annual change in total UK household wealth in £ millions. This shows that 2020 and 2021 contained some of the highest annual increase in household wealth of the last decades, and that around half of wealth changes are driven by changes in value of dwellings and land. Source: ONS, 2023.

This rise in apparent wealth largely accumulated thanks to the increasing value of our homes. In 2021, the ONS data estimates that the value of UK households’ land and property rose by £0.57 trillion. [1] This contributed two thirds (66%) of the overall increase of £0.9 trillion in household wealth that year (Figure 2). This is often the case: the changing value of homes and land have been the single biggest driver of household wealth records regularly since 1996 (Figure 2), often reaching above 90% of estimated wealth changes. The OECD estimates that the UK has the highest proportion of it’s recorded wealth tied up in land of any G7 country.

Of course, household wealth, and wealth gains, are not evenly distributed. Those who have not bought property do not gain wealth, and this trend maps structural inequalities in society: the average white household gained £115,000 in property value in the past decade, while the average Black household accumulated nothing at all. Almost half of housing, by value, in the UK is owned by the over-65s. Average house prices in London are significantly higher than in all other regions of the UK. The Resolution Foundation reports that those in the poorest 30% of households of the UK do not own homes, and therefore did not benefit from increasing housing values during the pandemic. At the same time, the richest 10% of families experienced an increase in the value of their homes of £44,000 per adult.

These apparent wealth increases have made investments in homes attractive to wealthy individuals, landlords and private investors. Over the last decades, those who sold homes saw huge windfalls thanks to decades of house price rises. Day-to-day, mortgage-holders typically spend less of their income on housing costs than those renting, and 35% have paid off their mortgage completely. Investors can enjoy low rates of tax on housing wealth compared to other forms of investment, and a favourable policy environment if they want to rent out homes for additional funds — analysis by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) and the Resolution Foundation has shown that income from employment has fallen behind the gains people get from owning assets. Wealthy individuals inevitably pass on the wealth in their homes to their friends and family, entrenching racial and demographic inequalities for decades to come.

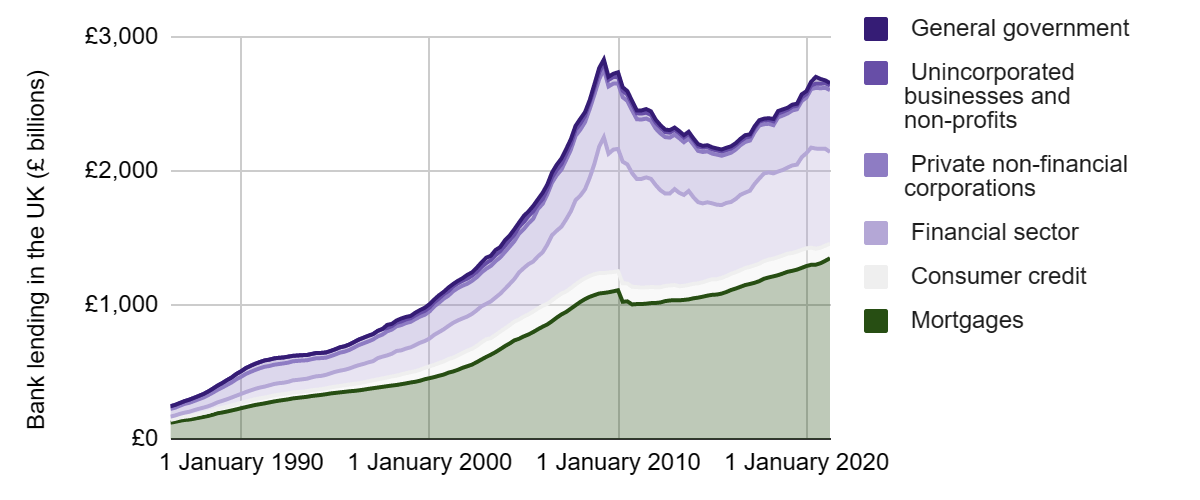

But while these benefits are considerable, the majority of the value of our homes is, for most people, never realised. Homeowners don’t completely lose the money they spend on mortgages, as renters do, but after decades of monthly payments they only recoup their home’s full value if they downsize or move to an area with cheaper average house prices. Homeowners can use remortgaging to secure lump sums of upfront cash for other uses, but this has become less common in the last 15 years, with households now storing more money in their homes than taking it out of them — before the 2008 crash, households took out more loans against their property than they repaid. [2] And many mortgage-holders have been saddled with unsustainable levels of debt: in December 2022, the Bank of England recorded that households have accumulated £1.67 trillion of mortgage debt, rates of mortgage defaults are expected to rise in 2023 thanks to the cost of living crisis, and there are an estimated 200,000 ‘mortgage prisoners’ trapped in overly expensive loan arrangements. The very wealthy can cash in on the value of their homes, and benefit from price rises, but most of us cannot.

Figure 3: UK bank lending. This shows that lending has rocketed since the 1980 Big Bang financial reforms, including to household mortgages. Source: Bank of England data, 2023.

This wealth mismatch is entangled with the banking system. Until the 1980s, mortgage lending was the preserve of building societies, while retail banks primarily lent to businesses and government. Following ‘Big Bang’ banking reforms in the 1980s that allowed and encouraged retail banks to offer mortgage lending, the amount of credit going towards mortgages skyrocketed: increasing 1000% since 1986. A full 50% of all UK bank lending now goes into mortgages (Figure 3).

This explosion of often poorly allocated mortgage lending (banks direct around a tenth of mortgages to Buy-to-Let landlords) drove up house price rises, which now suck up increasing proportions of homeowners’ income that could otherwise be used to purchase and invest in other things. The increased enthusiasm by banks to provide profitable mortgage credit also causes them to neglect lending towards more socially beneficial activity, such as growing local businesses or helping fund the green transition. UK banks allocate just 22% of their lending to organisations that might directly feed into the ‘real economy’: non-financial companies, non-profits and government (Figure 3).

The fact that most people are unable to use changes in the value of their home means that, even when house prices increase significantly, as they did during the pandemic, there is only a relatively small real world benefit. Increases are largely captured in bank, developer and landlord profits, inheritance windfalls and dents in the cost of living for some homeowners. This results in the perverse situation whereby UK households’ land and homes might nominally be worth £6,400 billion, but little of this can be leveraged for the £55 billion urgently needed to retrofit them by 2050, the £0.7 billion needed to alleviate fuel poverty for a year or the £2.5 billion a year spent by the NHS on housing-related ill-health. Our homes have been turned into financial assets.

When rocketing house prices during the pandemic were first observed, the Wealth Tax Commission, convened by the London School of Economics and Warwick University, argued that ‘introducing windfall taxes on the richest households would be the fairest and most efficient way to raise taxes in response to the pandemic.’ This might be true — the high pandemic profits accrued by property developers have certainly flown under the radar — but this would be a temporary fix for the perennial problem in the UK of our homes being treated as financial assets.

Many have argued that universally fairer taxation on property and land would dampen speculation by developers, investors and wealthy individuals, reducing the price of homes. It would also help capture increases in the value of homes as funds for social housing and public investment. This could mean reforming the current system, by updating council tax calculations and aligning Capital Gains taxes with income taxes, with higher rates for overseas non-residents, second homeowners and investors. Alternatively, abolishing Capital Gains, Stamp Duty and Council Taxes in favour of a single land tax, to better reflect the changing values of local areas and to capture rising property values for reinvestment in the local area, has had enduring popularity among economists.

Another way to ensure homes are managed as places to live, rather than opportunities to gain wealth through price speculation, is to increase the availability and dignity of alternative housing tenures, reducing our dependence on sinking money in property and expecting strong financial returns. Labour have committed to restoring social housing as the second largest form of housing tenure, and researchers and community groups across the UK have been exploring innovative forms of community-led and cooperative housing that provide stable, safe and low carbon homes. Last month, a House of Commons committee published recommendations for Private Rented Sector reform that included stronger tenant protections. These changes would present more affordable options for people, curb exploitative private renting, and rebalance the affordability gap between those who own and do not own homes.

Strengthening government and Bank of England oversight of mortgage and bank lending using existing macroprudential tools and goals would help regulate the supply and direction of bank credit. But we also need a new, more diverse ecosystem of banks whose primary purpose is to invest in productive and socially useful activities. In Germany, two-thirds of bank deposits are held by cooperative or public savings banks that are mandated to serve the public interest rather than maximise returns. Here, lending to non-financial businesses is significantly higher than mortgage lending at 40% and 30% of GDP respectively. [3] Not only does this mean more spending on infrastructure, local businesses and physical improvements like energy-saving retrofits, the house price-to-income ratio in Germany has been falling for most of the past four decades (although it has started to increase in recent years). This setup is complemented by a better regulated, more affordable rental sector, which makes homeownership less important to many Germans. Overall, less than 5% of people in Germany spend high proportions of their income on mortgages or rent, compared to a quarter of UK residents. [4]

These reforms — to taxes, tenures and bank lending — open up a pathway to a housing sector where we aren’t forced to spend so much on our homes, and more money goes into communities, green infrastructure, and local businesses. During the pandemic, our homes were apparently worth £6,400 billion, but hundreds of thousands of people fell into homelessness and fuel poverty, and 15% of the population lived in buildings that failed to meet decent living standards. We remain unable to retrofit, upgrade and properly maintain them. If we can create a system whereby homes are bought to be lived in, not profited from, we might start to be able to put our money where we actually need it.

[1] This may even be an underestimate — in 2021, the Resolution Foundation found that around 5% of the total wealth held by the very richest households (approximately £1 trillion) has been missed by official measures.

[2] The Bank of England has argued that this is due to households trying to pay down mortgage debt more quickly than pre-crash.

[3] Ryan-Collins, J. (2018). ‘Why can’t you afford a home?’. John Wiley & Sons.

[4] Defined as spending over 40% of income on mortgage or rent by the OECD.