UKEU

18 February 2026

Credit creation is a powerful tool wielded by banks, but bank lending data shows that most new money created is directed to buy existing assets, particularly property, and not to expand the productive economy or improve wellbeing.

Under the existing monetary system, bank lending is the primary way in which new money is created in the economy. In fact, approximately 97% of all money is created by commercial banks in the form of loans. Looking at who commercial banks are lending to therefore serves as a useful way to see which sectors of the economy our financial system is prioritising.

An analysis of bank lending data also gives us an indication of both the direction and the stability of the economy. Unfortunately, however, the lending data shows that banks are primarily lending to the financial sector and for the purchase of pre-existing assets, particularly property, thereby inflating asset prices rather than increasing real economic output or productivity. This is problematic since it means that wealth will become even more concentrated at the top than it already is, leading to increasing inequality between those who own assets and those who do not.

A decade and a half after the financial crisis, the problems of financialisation and asset bubbles are still with us. The financial crisis was caused by outsized lending to the property and financial sector, causing asset bubbles and instability, and the lending data shows clear signs that the monetary system remains geared towards financialisation and property speculation instead of supporting the productive economy.

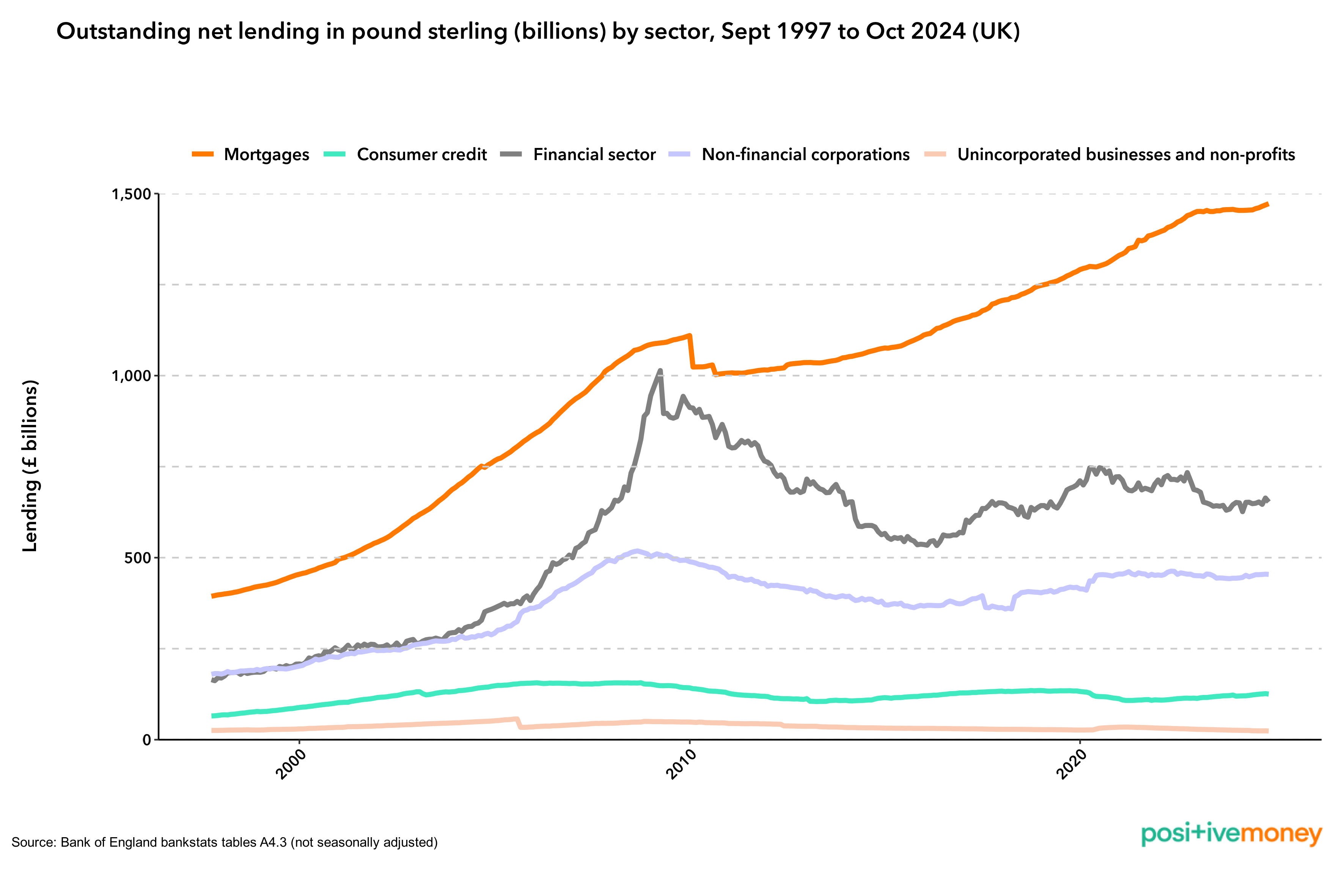

Figure 1 below shows the total outstanding credit in pound sterling held by different sectors of the economy, revealing that the nominal value of lending for house purchases has surged over the past two decades. Outstanding credit in mortgages stood at a record high of £1,472 billion as of October 2024. This means that lending towards mortgages has risen by £400 billion over 10 years, or by £717 billion over 20 years. Mortgages are the only type of lending that has seen significant increases in outstanding credit since the financial crisis, as bank lending to all other sectors has either fallen or stagnated since the crisis. The ever-increasing levels of mortgage credit is one of the main reasons property prices have skyrocketed in recent decades, and this development is interlinked with a deepening housing crisis in which more and more people are struggling to pay rent or are locked out from buying due to rising costs.

Figure 1

The stock of loans held by non-financial corporations, i.e. businesses that produce non-financial goods and services, is today at a lower level than in 2010, standing at £454 billion in October 2024. Given that CPI inflation since 2010 stands at approximately 51%, this means that non-financial corporations hold less than half of the outstanding credit today compared to 14 years ago in real terms. There is more than three times as much outstanding credit in mortgages today than that held by non-financial corporations.

It is welcome to see that levels of credit held by financial corporations have fallen from a high of £1,014 billion in March 2009 to £653 billion by October 2024. However, that is still 43.8% higher than that held by non-financial corporations, showing that the economy is still fundamentally geared towards financialisation rather than productive investment.

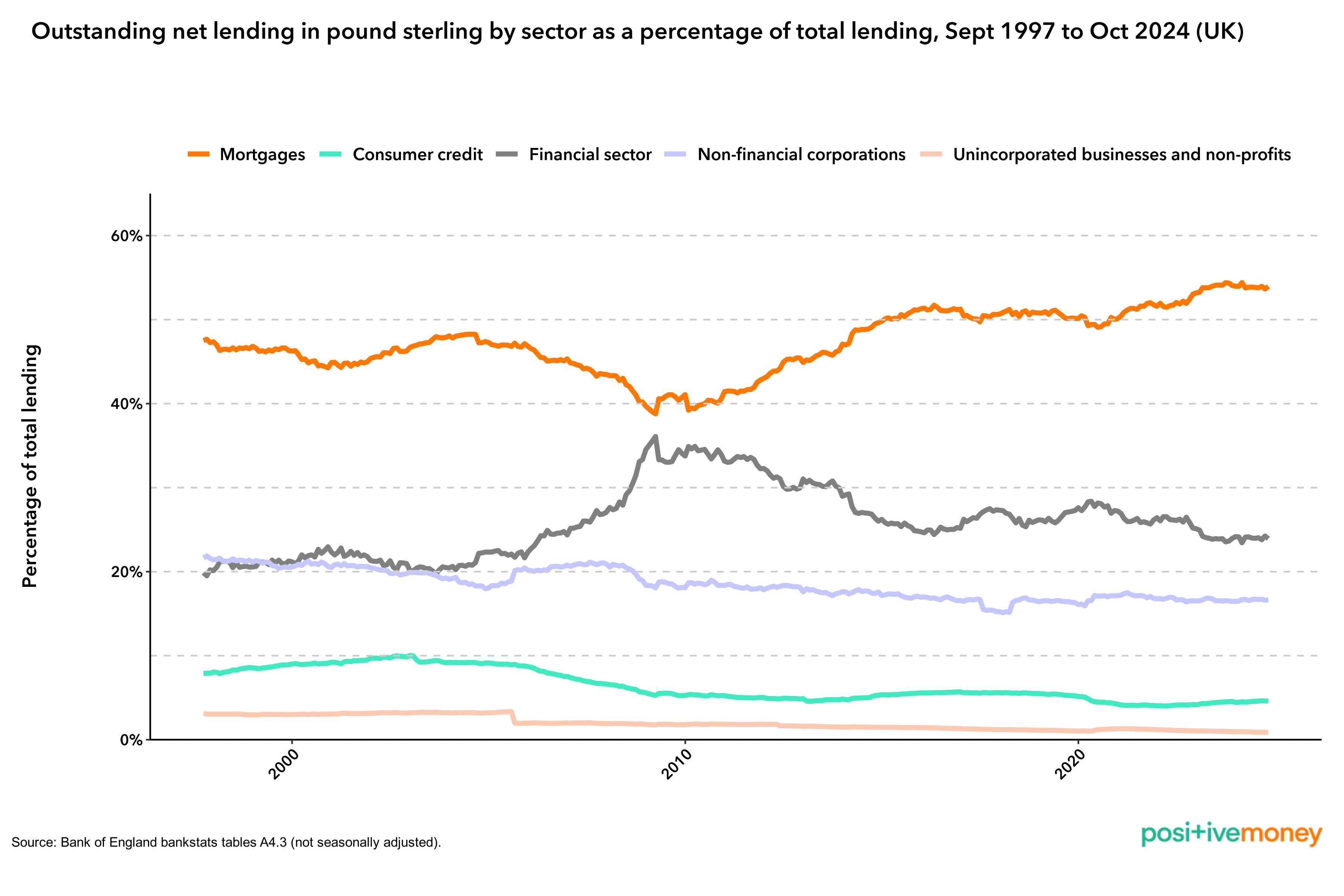

Mortgage lending now makes up 54% of all lending by commercial banks, up from a low of 38.8% in March 2009.

Outstanding credit held by non-financial corporations made up about 21% of total lending in the late 1990s, but now stands at only 16.6% as of October 2024.

The share of total outstanding credit held by the financial sector has increased from less than 20% in 1997 to 23.9% in October 2024. Although this is a much higher proportion of total lending than that held by non-financial corporations, it is a significant decrease from the high of 36.1% of total lending in March 2009.

The share of total outstanding credit held by unincorporated businesses and non-profits has seen the most dramatic decrease in relative terms, as in October 2024 this sector held less than 1% of total credit, down from approximately 3.2% 20 years prior.

Total lending held in consumer credit has also steadily declined from a high of 10% in December 2002 to 4.6% in October 2024.

Figure 2

The government could ameliorate the situation by increasing public investment and directing credit away from the financial sphere and towards productive sectors. This would be more than welcome, particularly since the UK has consistently ranked bottom in the G7 for investment.

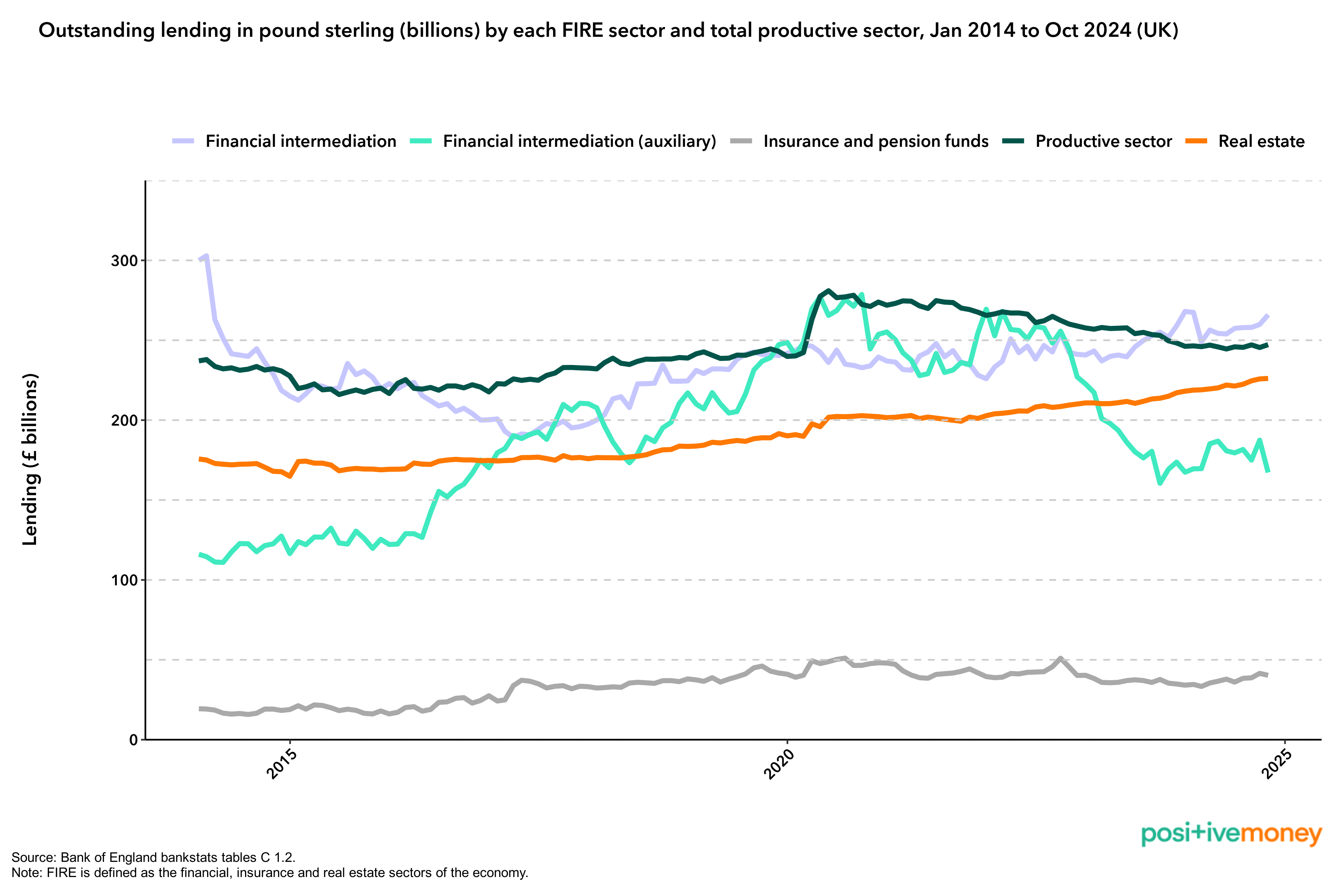

When analysing commercial bank lending to different industries in the economy we can see that the financial, real estate and insurance (FIRE sectors) receive much more credit than the productive sectors in the economy.

Figure 3

The Financial Intermediation industry (investment middlemen, such as banks) has received more credit than all productive industries combined.

Although the amount of outstanding loans to Activities Auxiliary to Financial Intermediation (such as hedge funds) has fallen in the past two years it still stands at £167 billion as of July 2024, an increase of 36.4% over 10 years.

Outstanding loans held by the Real Estate sector has steadily grown over the past 10 years, from £168 billion in October 2014 to £226 billion in October 2024, an increase of 34.6%.

Credit held by productive sectors combined stands at £247 billion as of October 2024, an increase of only 6.5% over 10 years, and a decrease of £24 billion compared to four years prior.

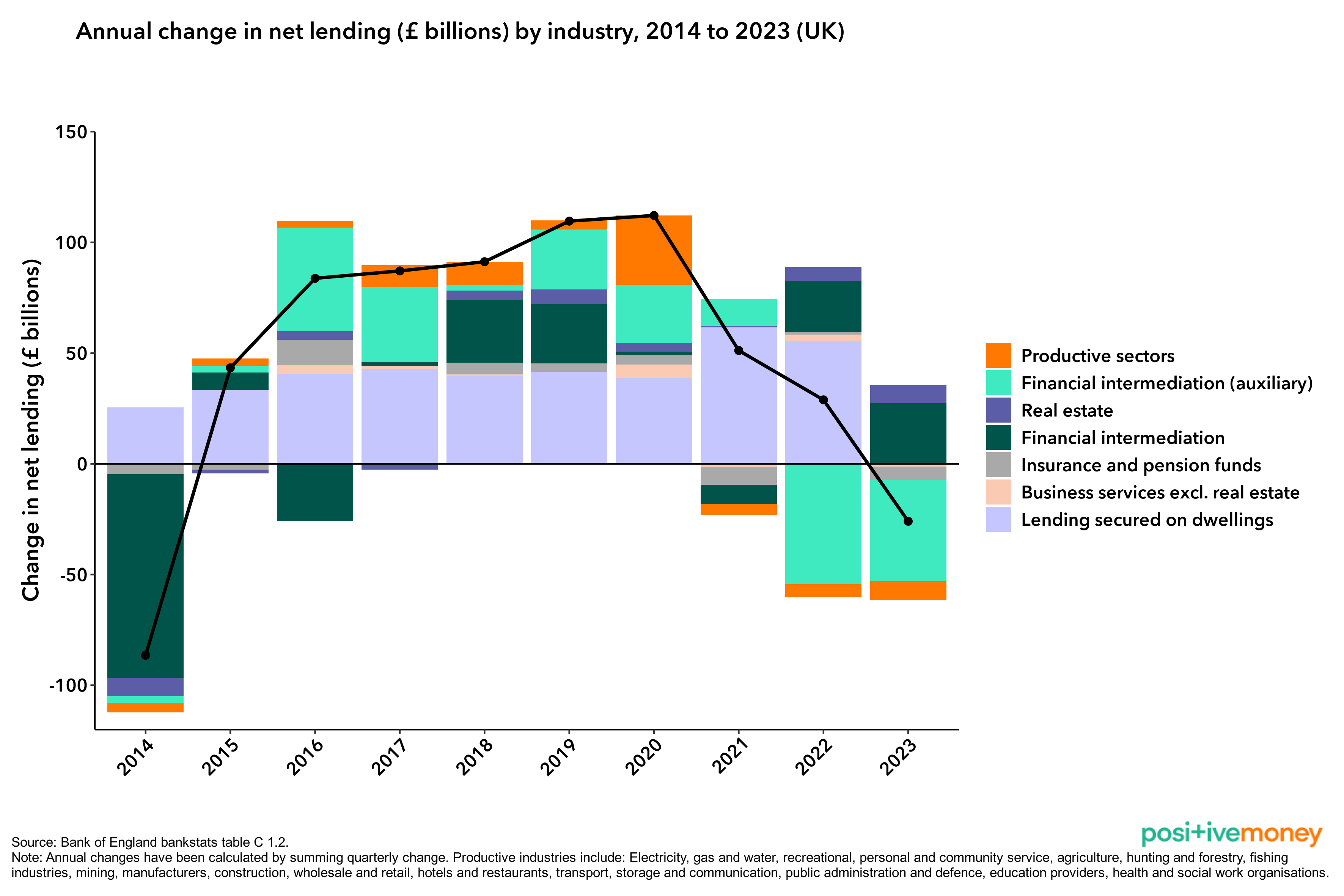

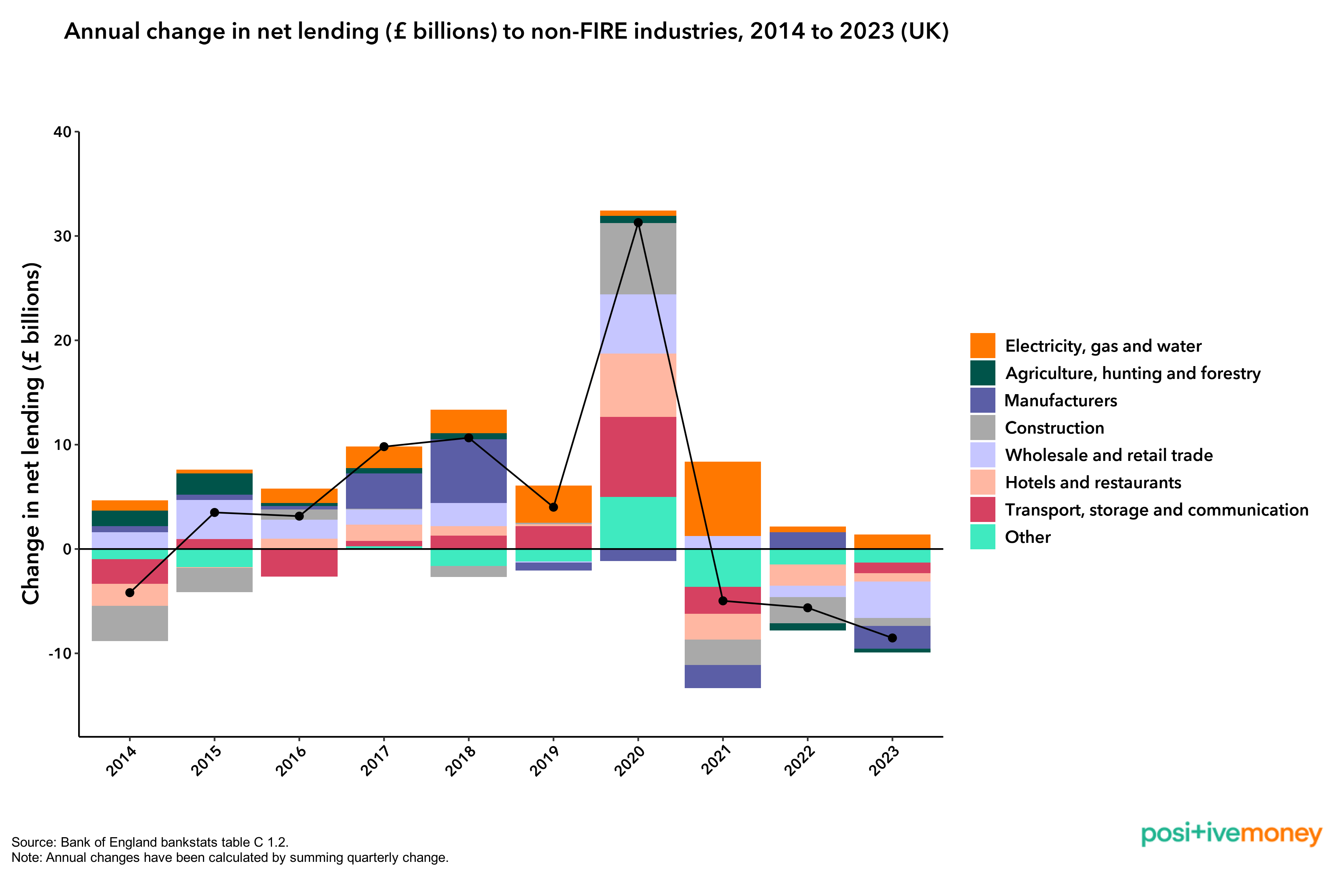

The annual change in net lending to productive industries has been negative for the past three years, as can be seen in Figure 4. Between 2015 and 2020, when growth in annual net lending to productive sectors occurred, the levels of growth were still significantly lower than for lending towards mortgages or financial intermediation activities. Mortgage lending has been particularly prevalent, with high annual growth every year between 2014 and 2022, although only growing by £153 million in 2023, likely because of higher interest rates. Furthermore, the annual change in total net lending, represented by the black line in Figure 4, has fallen steadily since 2020 and was negative in 2023 for the first time since 2014.

Figure 4

Figure 5 shows the annual change in net lending to different productive industries, and we can see that levels of growth are either negative or far below that of the FIRE sectors.

Electricity, Gas and Water is the only productive industry that has seen sustained annual growth in lending since 2014. Boasting the largest increase in annual net lending in 2023 out of all the non-FIRE sectors, it still only stands at a meagre £1.4 billion. This is miniscule in comparison to the largest increase within the FIRE sectors in 2023, which was the Financial Intermediation sector at a whopping £27.1 billion.

Manufacturers and Construction have seen their change in annual net lending fall in three out of the past four years. This stands in stark contrast to the high growth in lending to mortgages and real estate, suggesting that growth in the property sector is more due to increased lending and asset-price inflation rather than high output.

The combined annual net change in lending for the ‘Other’ category of industries (includes Fishing, Mining and Quarrying, Public Administration and Defence, Education, Health and Social work, and Recreational, Personal, or Community Service) has fallen in eight of the last ten years.

The annual net change in lending to the productive sectors of the economy decreased by £5 billion in 2021, by £5.6 billion in 2022, and by £8.5 billion in 2023.

Figure 5

Although the annual change in net lending to productive industries was positive between 2015 and 2020, it is worrying that it has seen three consecutive years of negative growth. Furthermore, when growth was achieved between 2015 and 2020 it was at significantly lower levels than the growth achieved in the FIRE sectors.

Indeed, the situation is considerably different in the financial sphere, as changes in net lending for mortgages, real estate and financial intermediation over the past three years have seen considerable growth. In fact, the stock of loans held by productive industries has only grown by £15 billion over the past 10 years, while lending towards mortgages grew by £400 billion during the same period.

However, it is worth noting that this data only contains commercial bank lending and does not include lending from non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs).

The problem here is clear and persistent – credit is directed to sustain asset bubbles rather than expanding wellbeing or productive sectors. This situation is a direct result of the liberalisation and deregulation of credit markets which research has shown is significantly associated with a higher share of total lending going towards financial and speculative activities instead of the real economy. The lending data shows that very little has changed since the financial crisis, as most new money is created for purchasing existing assets, such as property, or for speculative activity in the financial sector.

The share of total lending going to non-financial sectors of the economy has fallen by approximately three percentage points since the financial crisis, and lags far behind lending towards mortgages or the financial sphere. This is worrying, since it implies that the foundations of our financial system are not based on increasing productivity or innovation, but instead relies almost entirely on asset price inflation. Although this may maximise short-term profit for the financial sector, it is a barrier for boosting wellbeing through increases in productivity or innovation, and it heightens the risk of a financial crisis. Asset bubbles can only be sustained for so long and will eventually burst as they rely on fictitiously boosting asset values without increasing real economic output or boosting productivity. Wellbeing and improvements in innovation and productivity can only be increased through investments in the productive sectors of the economy, but the monetary and financial system is not working in a way that supports the real economy.

The current monetary system and its incentives also have wider impacts on the health of the economy. For example, the financial and monetary system plays a significant role in the housing crisis in terms of causing inflationary pressure in the property market, benefitting property-owners at the expense of the rest of society. Creating money for speculative activities in the financial sphere also has impacts on wealth inequality, as income from capital will grow faster than wages. This can quickly create a feedback loop where credit becomes even more concentrated in the financial sphere, as investments in the real economy are unable to yield the same profits as that achieved by inflating asset prices.

Overall, the lending data suggests that the financial and monetary system is ill-equipped to support improvements in wellbeing, productivity or innovation through investment in the real economy. Creditors effectively guide the economy through their lending decisions, but commercial banks have clearly shown that they are unable to direct credit in a way that allocates resources efficiently.

The monetary and financial system must be reformed so that new money is created for the purposes of improving wellbeing and tackling societal challenges such as poverty, climate breakdown, or the housing crisis. In order to achieve this change we must utilise effective credit guidance instruments to ensure that the real economy is supported. We must also embrace the opportunity of a National Wealth Fund to direct investments towards the green transition and public infrastructure projects which the private sector is reluctant to invest in. It is time we recognise that a deregulated credit market does not optimise resource allocation in the economy, but instead shifts resources away from productive sectors in the search for short-term profits - to the detriment of the economy as a whole.