UKGlobal

27 January 2026

April 27, 2023

In a new briefing, Positive Money looks at how the housing crisis is experienced by different ethnic groups in England and Wales, and sets out the urgent need for serious long term plans from policymakers to halt the invasion of our homes by financial interests, grow the social housing stock, and protect people from poor quality, unaffordable and overcrowded homes.

Last week, Positive Money published a new analysis of the latest housing census data, exploring the impacts of the housing crisis on different ethnic groups. [1] The results were shocking: since 2001, ethnic minority households have been around a quarter less likely to own their own home than the national average; 14% of ethnic minority households are overcrowded; and the much-discussed decreasing rates of homeownership across the country are almost entirely driven by persistently low and decreasing rates of homeownership among ethnic minority households. In this blog, we explore the picture at the London-level, where rental prices have shown particularly extreme fluctuations in recent years, and which is home to the highest proportions of ethnic minority households in England and Wales.

In London, around half (47%) of all households own the home they live in (Figure 1), significantly lower than the national average (63%). White British households in London are more likely to own their own homes (59% homeownership rate), which is reasonably similar to Indian (66%), Chinese (57%) White Irish (54%), Mixed White/Asian (50%), and Pakistani (48%) households. However, other ethnic groups have a significantly lower homeownership rate: just a fifth of Black African London households own their home, a quarter of Bangladeshi (28%), Mixed White/Black Caribbean (24%), Mixed White/Black African (23%) households, and a third of Black Caribbean (35%) households.

It is also striking that not only are many ethnic minority groups in London less likely to own homes than others in London, they are significantly less likely to own their home than other people of their ethnic background outside of London. While 9% fewer White British households own their home in London compared to White British households in other regions, the equivalent gap is higher for other ethnic groups: Bangladeshi households (23%), Pakistani (14%), Black Caribbean (13%, Mixed White/Black African (12%), Mixed White/Black Caribbean (11%), Black ‘Other’ (10%). The 23% gap for Bangladeshi households is particularly acute: 51% of Bangladeshi households outside of London own their home, compared to just 28% of Bangladeshi Londoners. This means that homeownership rates are particularly low among many ethnic minority communities in London, and they are likely to be more affected by the choice to live in London than White British households are.

Figure 1: Homeownership rates by ethnic group, in and outside of London (2021).

Source: author’s elaboration of Census data.

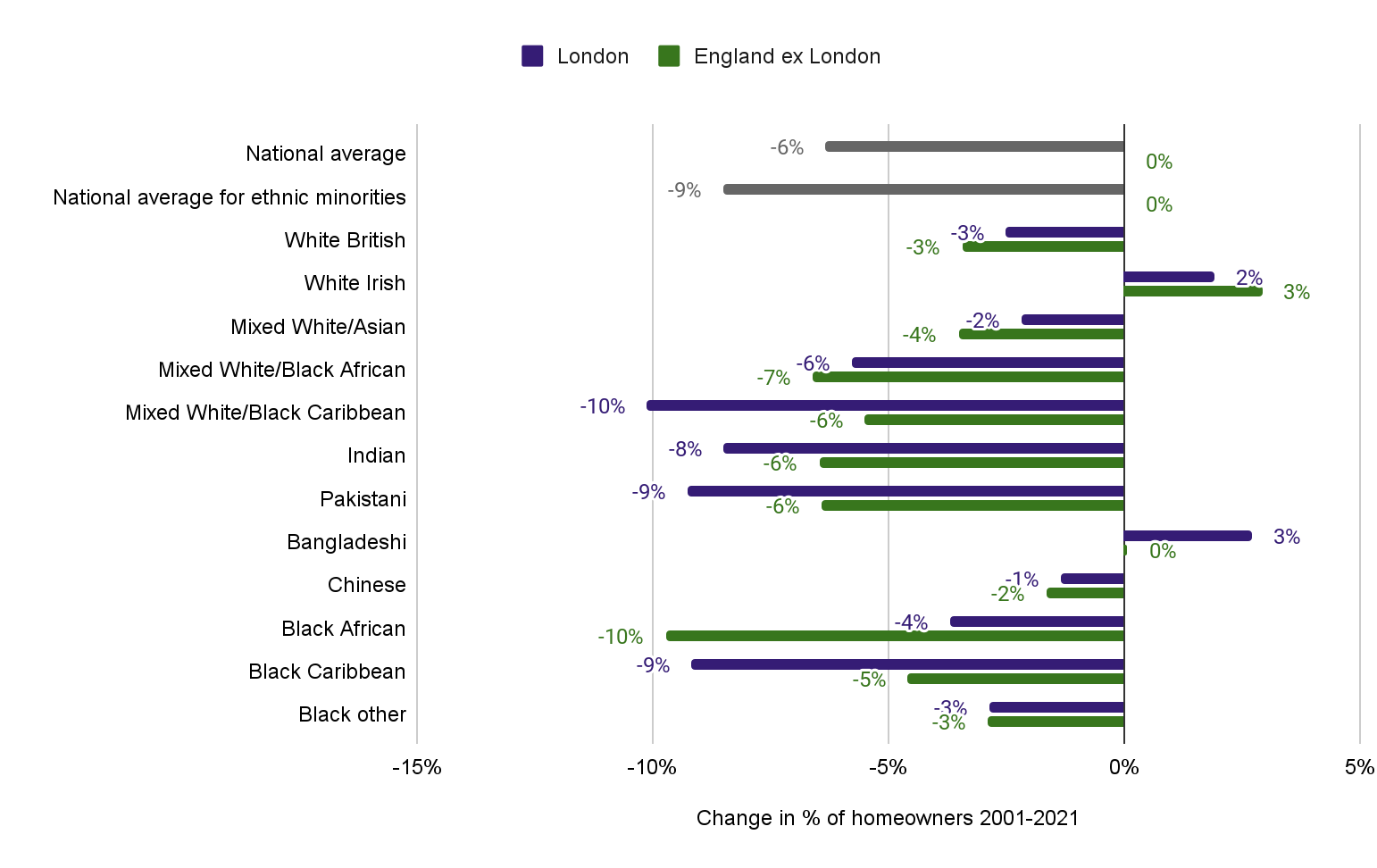

The disproportionate impact of the housing crisis on many ethnic groups in London has also worsened over time. Since 2001, national homeownership rates have dropped 6%, from 69% to 63%. The overall London homeownership rate decreased from 56% to 47%, a drop of 9%. Our analysis has found that this decrease is largely due to an increasing proportion of people from ethnic minority backgrounds in the population, who are persistently less likely to own their homes, and large drops in homeownership rates among some ethnic minority households.

As Figure 2 shows, among London’s Mixed White/Black Caribbean, Indian, Pakistani and Black Caribbean households, there has been nearly a 10% drop in homeownership rates over the last twenty years, compared to drops of around 4-7% for these ethnic minority households nationwide and drops of around 3% for White British households nationally. In a few cases, the decrease in homeownership was smaller in London than in other parts of the country — the proportion of White British and mixed White/Asian households owning their homes dropped around 3% outside of London, and 2% in London. 10% fewer Black African households owned their homes outside of London, compared to 4% fewer in London.

Overall, the housing crisis was already significantly worse for ethnic minority Londoners in 2001, and it has worsened for them more acutely over the last twenty years than their White neighbours and other ethnic minority households in other parts of the country.

Figure 2: Change in the % of homeowners for different ethnic groups across England & Wales compared to London, between 2001-2021.

Source: Author’s elaboration using Census 2001 and 2021 data. Not all groups are listed due to small data sizes.

High homeownership rates are not necessarily the be all and end all — many countries have housing systems where the majority of people live in social, community and rental housing. But in England and Wales, homeownership is viewed as a critical route to building wealth and financial security, and tends to be more affordable and better quality than renting, as explored below. As inherited wealth becomes increasingly important to peoples’ ability to buy a home, thanks to the structure of our current housing system, the children of renters may also remain renters, perpetuating the homeownership gap for generations.

Low homeownership rates means more people renting, and renting in England and Wales is currently on average more expensive, per month, than paying a mortgage. The government defines ‘unaffordable’ rent or mortgage payments as being 30% of monthly income. In London, Greater London Authority data indicates that White Londoners who rent privately typically spend 29% of their income on rent, compared to 35% for Black Londoners and 36% for Asian Londoners. All social renters in London are spending close to the 30% affordability limit.

The greater presence of Black, Asian and ethnic minority households in the private and social rented sector leaves them more exposed to the higher levels of insecurity and lethally unsafe housing conditions that are more common in these tenure types. The death of two year old Awaab Ishak last year, who died due to damp and mould in his family’s socially rented flat, brought greater public awareness to these conditions, though campaigners have demonstrated that this was by no means an isolated case.

We didn’t look at London-specific data in relation to quality of living, but our research shows that conditions for many groups in England and Wales are persistently crowded and precarious — and not getting safer quickly enough. 14% of ethnic minority households are overcrowded (15% in 2011). This is 3.5 times greater than the 2021 national average (4%). A full 28% of Bangladeshi households are overcrowded (down 2% since 2011), 21% of Black African households (down 1%), and 21% of Pakistani households (down 2%).

The quality of homes is also improving more slowly for ethnic minorities than the national average. In 2011, about a quarter (23-25%) of all English and Welsh households lived in unsafe homes, regardless of ethnicity. In 2021, this improved to 15% for white households, but remained at 18% for Asian households, and 21% for Black households.

Renters in England and Wales live at risk of being evicted by their landlords, or their contracts not being renewed, and this causes anxiety and stress. A recent Joseph Rowntree Foundation study showed that eviction rates are higher in the most ethnically diverse local authorities in London compared to the least ethnically diverse. Racial discrimination likely exacerbates this: between 2014-2018, 25% of Black Londoners surveyed gave their reason for their most recent house move as ‘landlord asked me to leave’, compared to less than 5% of White Londoners.

Black households are twice as likely than the average household in London to be assessed for homelessness [2], and Black Londoners are five times more likely than White Londoners to be statutorily homeless. While the majority of rough sleepers in London are White, Trust for London analysis highlights that the number of Black rough sleepers is rising, having increased fourfold between 2008/09 and 2020/21.

In addition, for those seeking new homes, there is widespread and under-reported discrimination against prospective renters. Journalist Carla Abreu has traced barriers starting at the point of requesting viewings for homes, and continuing as renters try to put down an offer, or request support from their landlord once they live in the home. She notes that the Right to Rent scheme, which ‘requires landlords to deny lodgings to those who cannot prove they are permitted to live in a rented home’ enables these barriers, with 42% of landlords saying that the scheme would make them “less likely to consider letting to people who didn’t hold a British passport — or who ‘appeared to be immigrants'”.

The housing crisis is particularly acute for ethnic minority households in London, and this has under-recognised implications for how policy-makers, campaigners and politicians in government and London might approach reforming how our homes are managed.

1. Including structural and demographic features of the housing crisis in analysis and recommendations. Declines in average rate of homeownership are primarily due to persistently low or declining homeownership rates among ethnic minority households. This is rarely acknowledged by policy-makers and politicians keen to raise homeownership rates. Government data on the affordability of housing for different ethnicities is released irregularly, research from the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, and academia and industry groups rarely disaggregates findings by ethnicity. There is also a lack of focus on the systemic financial and wealth drivers of house price rises among many politicians, campaign groups and lobbying organisations, which is holding back progress in closing deep-rooted housing inequalities.

2. Recognising that a two-tier housing system is emerging. The dire situation for Black, Bangladeshi, Pakistani and other ethnic minority groups starkly illustrates the consequences of our homes being turned into financial assets. The government has encouraged investment in homes to store and gain wealth, raising prices to the extent that we effectively have two separate housing systems. On the one hand, those who own homes and thus generate wealth passively through rising house prices, often reinvesting this (through second homes or passing wealth to their children) into other homes, further raising prices. On the other hand, there are those who are trapped into expensive rental arrangements, with limited ability to accrue enough wealth to get on the so-called ‘ladder’. The latter group includes the majority of Black, Bangladeshi, Mixed Race, Arab, Roma and Traveller communities. This is often acknowledged implicitly in the analysis of politicians, industry, media and campaigners, but the debate rarely captures the overall failings in the design of the English and Welsh housing system and the long-standing political failures that have brought us here.

3. Committing to long-term, profound changes to the management of our homes. Our research aligns with arguments made by countless other researchers and campaigners: the inequalities in the housing system are extreme, and piecemeal efforts to build more homes and increase mortgage availability will not be sufficient to solve them. Deep cultural, political and regulatory reforms are needed to bring house prices down, including regrowing the social housing stock, alongside government commitments to long-term house price stability and ending the use of homes as investment vehicles.

4. Increasing the affordability and quality of social, cooperative and rented homes. Housing Ministers must ensure that all forms of housing tenure — renting, cooperative living, homeownership and new structures — are equally affordable, dignified and stable, among all demographics. This is essential to tackling the two-tier system that is emerging and giving people the freedom to choose how they live in their home. These efforts must include tackling the racist consequences of right to rent policies, and strengthening protections for tenants against racial discrimination from landlords and estate agents.

Access to the full briefing is available here: The Impacts of the Housing Crisis on People of Different Ethnicities.

[1] In this article, we attempt to highlight specific ethnicities we are discussing whenever possible. We recognise that the term ‘Black, Asian and ethnic minority’ or BAME has limitations and has been criticised for treating ethnic minorities as a homogenous group in England and Wales. Much of the data used in this research is not sufficiently disaggregated due to small sample sizes and where the data uses specific terminology, for consistency we have used the same wording.

[2] Cosh, G. and Gleeson, J. (2020). Housing in London 2020 – The evidence base for the London Housing Strategy. Greater London Authority.