UKGlobal

27 January 2026

If Labour wants to deliver on their missions, resist austerity and win the next election, they may have to depart from the failed orthodoxy that favours free-reigning financial markets hand-in-hand with fiscal and monetary austerity.

Since the Liz Truss episode, political commentators have developed a new interest in the daily movements of government bond (gilt) markets. This has been bad news for the Chancellor Rachel Reeves, with gilt prices falling, and therefore yields (effective borrowing costs) rising to higher levels than the infamous ‘mini-budget’ peak.

From a historical perspective, recent gilt yields are still far from extreme - throughout much of the 20th century governments would have been happy to borrow long-term at less than five percent interest. The issue today is that such yields represent higher real interest rates which are harder to sustain, given that we have lower growth and a stricter 2% inflation target. Large stocks of government debt, which are unlikely to disappear anytime soon for good reason, mean that government fiscal policy is increasingly at the mercy of interest rates set by central banks, which have been kept high in an attempt to manage inflation.

Though gilts have since seen sharp moves in the other direction, suggesting that previous fears were overstated, markets seem to have already pressured the government into committing to further spending cuts. However, as the events of the last 15 years should have proved, austerity will only make it harder for the government to meet its fiscal rules, by reducing growth and tax revenue.

Before returning to the doom loop of the previous government, we should consider the degree to which the UK’s problems are being driven by the current monetary and regulatory orthodoxy.

Government bond yields generally reflect expectations of future interest rates - so why did yields rise so highly at a time when the Bank of England is expected to lower interest rates?

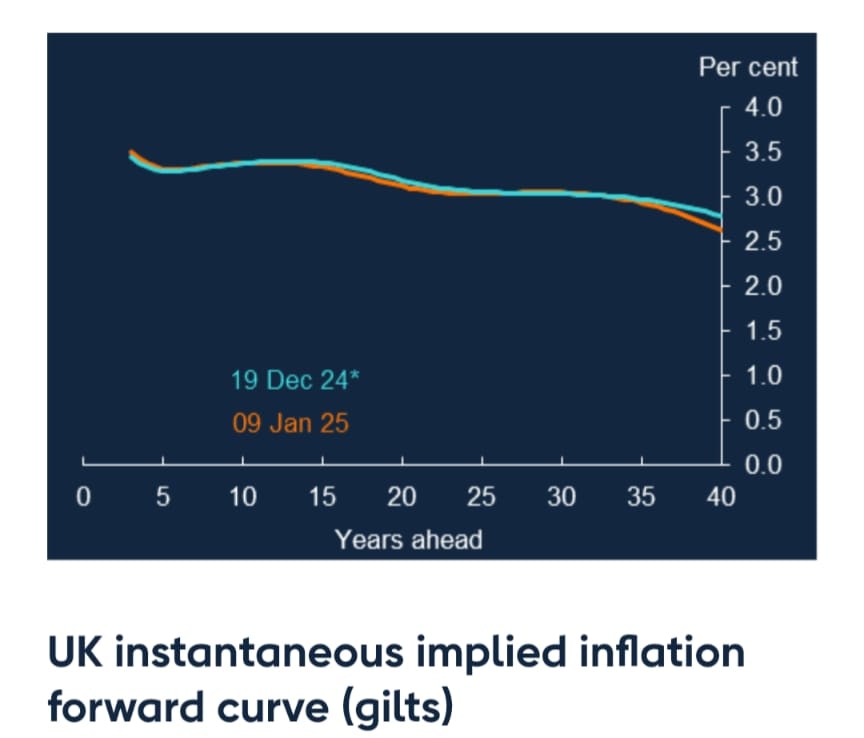

The way in which gilt yields rose suggested investors were demanding a premium for holding longer-term government debt, referred to as ‘term premium’. Such term premia can be driven by a number of factors. It can be the result of longer-term bonds being less liquid, but liquidity issues did not seem to be in play, given that recent gilt auctions were greatly oversubscribed, even for longer-duration gilts. An increase in term premia may suggest some sort of default risk, either implicitly via inflation or legal default. However, markets weren’t pricing in higher inflation - as the below inflation forward curve published by the Bank of England showed, market inflation expectations actually seemed to fall. Concerns over debt sustainability also don’t seem to be the answer, as UK debt-to-GDP isn't abnormally high compared to other countries (setting aside the fact the UK issues its own currency and so has no reason to legally default on its debt).

A more plausible explanation for higher gilt yields is that the movements are part of a global increase in yields, driven by expectations that the Federal Reserve will respond to recent economic data and a Trump presidency with a tighter monetary policy stance. This would explain why gilt prices seemed to rally in response to US economic data, rather than the Treasury’s messages to the market.

Yet, this does not explain why the UK debt suffered worse than other countries’. The answer to this may lie in how the UK is particularly exposed to global financial volatility, for which there are perhaps two principal (interrelated) reasons. Firstly, the UK runs both large government deficits and current account deficits, which means it relies on net borrowing from the rest of the world, and foreign investors will be pricing in reference to global interest rates (which are essentially set by the US Fed). Secondly, the relative size of the UK’s financial sector, and policymakers’ impulse towards deregulation to maintain its ‘competitiveness’, may also exacerbate this vulnerability.

The question should be asked of what role the UK’s large and unchallenged financial markets played in recent gilt market turmoil. There may be evidence for this at least in the views expressed by market participants - as reported in the FT, “M&G Investments’ Andrew Chorlton, chief investment officer for fixed income, said at an event that hedge funds “looking to make a quick buck” appeared to have played a large role in seeing how low they could push gilts.” If the Bank of England is not going to intervene to support gilt prices, this may be a safe bet for investors to make.

The existential role of central banks, which can be traced back to their founding, is to support government debt as a risk-free asset upon which the financial system depends. The Bank of England should therefore lean against investors’ judgement that they could push yields higher, especially if markets’ behaviour implies that government bonds are somehow unsound assets. Practically, this could look like yield curve control, as most famously exercised following World War II and more recently in Japan, in which the central bank commits to buying bonds to put a floor on prices according to an orderly yield curve. Doing so would quickly put an end to speculative attacks on gilts. Such an outcome could even be achieved through the words of central bankers alone, without the need to make any purchases, as was the case when former European Central Bank governor, Mario Draghi, managed to see off speculators by uttering the famous commitment to do ‘whatever it takes’. At the very least the Bank of England should make it clear that there is no risk of sovereign default.

Unfortunately, little support is likely to come from the Bank of England in our current environment, given that policymakers have decided that monetary austerity is necessary to slay inflation, through mechanisms that are rarely spelled out. In this context, recent turmoil can be seen as a feature rather than a bug of the system.

If the Bank of England is unwilling to intervene because of the current ill-founded orthodoxy, regulators should at the very least curtail the ability for markets to dictate fiscal policy through speculation.

A principal means through which financial institutions like hedge funds can push down gilt prices is short-selling, in which investors borrow an asset, sell the asset and then buy it back at a lower price before returning to the lender, profiting from the fall in prices. Short Selling Regulation (SSR) carried over from the EU gives regulators the power to restrict short-selling in order to prevent a disorderly decline in the price of a financial instrument, or in response to a serious threat to financial stability or market confidence.

However, the previous government’s pursuit of financial deregulation, enthusiasm for which has carried over to the current Labour administration, has weakened the SSR regime. Perhaps most alarmingly, the government has removed requirements for investors to report short positions for sovereign debt, including gilts. This would presumably make it more difficult for regulators, let alone the general public, to understand the degree to which falling gilt prices are being driven by speculative attacks.

Proponents of short-selling argue that it plays an important role in price discovery, pointing to how short-sellers were able to bring down Ponzi schemes such as Enron. But the utility of short-selling sovereign debt is much less clear, especially if the market volatility it exacerbates puts pressure on the government to pursue damaging austerity.

In a more sensible world, you might hope that any lender found to have financed speculative attacks against public assets and therefore harmed public welfare, would have their license removed by regulators. Unfortunately, the logic driving the deregulation of recent decades is that financial liberalisation and more liquidity, supported by more trading, enables more ‘complete’ markets, resulting in greater allocative efficiency. As former chair of the Financial Services Authority, Lord Adair Turner famously put it, much of the activities enabled by financial deregulation are ‘socially useless’. As the likes of Turner have powerfully argued, the benefits have been hugely overstated and the financial speculation required to deliver greater liquidity produces instability and harmful momentum effects, as we may have seen recently with gilt markets.

Such dynamics are not contained to gilt markets. It has been argued that post-pandemic inflation was exacerbated by dramatic changes in commodity prices amplified by financial market speculation via derivatives.

Unfortunately, these socially useless, and even harmful, activities are the kind the government may be seeking to embolden with its strategy to increase the growth and competitiveness of the financial services sector. As we have argued in our response to the government’s call for evidence on the subject, a large body of empirical evidence shows that, beyond a certain threshold (which the UK has passed), the growth of the financial sector harms the wider economy.

Much of the literature focuses on how this ‘finance curse’ manifests through more frequent and more severe financial crises, as well as through misallocation of resources and ‘brain drain’ effects. But recent events suggest there may also be a less considered fiscal dimension, if a larger and more loosely regulated financial sector can amplify bond market volatility, threatening the government's fiscal rules, leading to austerity, which leads to lower growth and a self-reinforcing doom loop.

If Labour wants to resist austerity and win the next election, they may have to depart from the failed orthodoxy that favours free-reigning financial markets hand-in-hand with fiscal and monetary austerity. Rather than competing in a regulatory race to the bottom and attempting to cut their way to growth, the government can do much more to achieve its missions by aligning finance with public purpose and launching a long-overdue review of the UK’s monetary policy framework to ensure it is fit for the challenges of today.