EUUK

3 July 2025

‘Climate finance’ commitments are woefully inadequate while inequalities in currency power force Global South countries to extract environmentally costly goods, and export them to the Global North. To end the outsourcing of emissions and remove the restrictions imposed on climate vulnerable countries, we need a new international monetary system.

As COP26 has drawn to a close, many have expressed bitter disappointment at the absence of any firm commitment from world leaders to end the extraction of fossil fuels. The UK was quick to pass the blame on to India and China for failing to commit to a coal phase-out. However, this fails to recognise that the international monetary system forces poorer countries to extract and export natural resources to fuel rich countries imports.

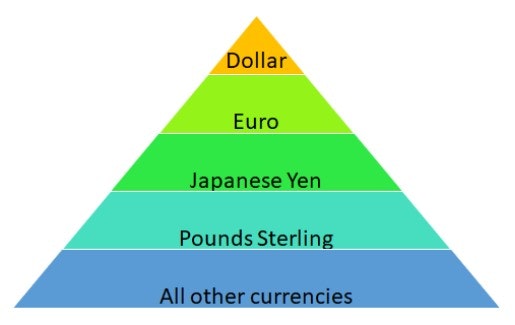

Different currencies do not exert equal power. Rather than simply facilitating a web of international transactions, currencies themselves create and reproduce monetary hierarchies. This hierarchy can be imagined as a pyramid, with the most powerful currency, the dollar, at the top.

Source: International Monetary Fund, Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves, Q2 2021

Currency power is determined by the international demand for a national currency, to carry out trade, to store savings, or to settle international debts. The ease with which dollar-denominated assets can be converted into cash creates a consistent demand for US Treasury bonds and dollar reserves, which make up 60% of all global foreign exchange reserves. Beneath the dollar sits a layer of other wealthy country currencies, such as the Euro or Yen, which make up a further 25% of share of foreign exchange reserves. At the bottom of the pyramid are many Global South countries with weak currencies, which cannot use their own currency on international markets. Many of today’s powerful currencies have their historical roots in colonialism and empire, often established through coercion and used to siphon off wealth from their colonies. These racialised hierarchies are continually resisted in the post-colonial countries in which they are imposed.

Dominant currencies benefit from certain structural privileges. The global demand for a handful of currencies creates a huge source of revenue for the countries that produce them. The ease with which core countries are able to attract capital allows them to keep interest rates low and run significant trade deficits (when a country’s imports are worth more than their exports) without consequence.

Countries with powerful currencies have undue influence over international institutions. The US, at the helm of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), has made its lending to the most climate-vulnerable countries conditional on programmes of severe austerity (known as structural adjustment programmes). This reduces the policy and fiscal room for these countries to develop their economies away from resource extraction and low value exports. Meanwhile, core countries exempt themselves from these rules. Building on their wealth, Global North countries are able to continually import energy and labour intensive goods, and build the industrial capacity to export high-value goods.

In the Global South, countries with weak currency power lack the monetary sovereignty to create new money, or to make decisions about setting their own interest rates. Due to the lower liquidity (ability to turn financial products into cash quickly) of these currencies, central banks must offer higher interest rates to attract capital, which makes borrowing more expensive for domestic businesses. The unreliable flow of capital means that ultimately poorer countries must rely on exports to finance their imports. Governments are under sustained pressure to extract and export energy and raw materials (sometimes called “embodied nature”) to make ends meet. In one year alone, 10.1 billion tons of natural raw materials moved from the Global South to the North. So, while rich countries import, consume and emit unchecked, the social and environmental consequences are felt elsewhere.

This cycle is continually reinforced. When peripheral countries do not sufficiently export raw materials, they are dependent on foreign investment to make ends meet. The paying of interest and fees on foreign debt accelerates the flow of capital from Global South to North and keeps peripheral countries in debt bondage. During 2020, when governments should have been focusing their spending on both the health and climate crisis, countries in the Global South spent $327 billion on servicing debt. At best, this restricts the funds available for tackling climate change. More realistically, this foreign debt actively encourages more environmentally harmful practices, with countries resorting to deforestation, mining, and the burning of fossil fuels to service their debts.

Within this structure, even pledges of international climate finance become warped to meet the predatory tendencies of the system. In 2009, the Global North committed to sending $100 billion a year of climate finance to developing countries. This is already a drop in the ocean compared with the $327 billion that Global South countries send per year to the North in payment of debt. Wealthy countries have leveraged their currency power to delay urgently needed climate finance to 2023. To add insult to injury this is being delivered through the form of unjust market rate loans instead of grants. Countries on the front line of climate change are being plunged further into debt with high interest rates and strict repayment schemes, meaning they will pay an even higher cost for a crisis they have not caused.

As climate finance has been allowed to flow through the market, these investments have been delivered in the form which will have the highest return, rather than meet the highest need. Small Islands and Developing States (SIDS) on the front line of the climate crisis have been consistently demanding funding for loss and damage to deal with the fatal impacts of climate change happening right now. Countries historically responsible for emissions, have a responsibility to deliver these climate reparations: owed for both past and present exploitation of formerly colonised countries. Instead, however, funds have gone overwhelmingly to mitigation of future impacts.

It is time for the Global North to listen to the voices in the Global South which have long called for a transformation of the unjust international monetary system. Scaling up grants and offering debt cancellation for climate vulnerable countries would be a step in the right direction. This would enable the Global South to have the resources to respond to the urgent extreme climate events that they are facing, rather than paying huge sums of money to external markets.

More fundamentally, rather than responding only to the symptoms of a broken system with false promises of climate finance, policymakers must urgently consider how to create an international monetary system which is consistent with a habitable planet. First, a truly international reserve currency needs to be developed, rather than one which gives unfair economic advantages to the worst emitters. Keynes’ proposal of an international clearing union which would develop a global unit of account (or an international currency) provides a useful starting point.

This would begin to remove the power imbalance between debtors and creditors, and enable periphery countries to invest in their own economies rather than paying for the deficit of core countries. The IMF already manages a ‘basket of currencies’, known as Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), which can be used as an international reserve asset in times of crisis. Barbados is calling on the world’s strongest economies to reallocate their allocation of SDRs to those countries that need them through a new global disaster mechanism to provide reserves which would be “targeted at vulnerability, fast, substantial, cheap, and unconditional”.

The delivery of climate finance, debt cancellation, and green liquidity are vital measures for climate vulnerable countries, and could save countless lives. However, periphery countries are not able to decarbonise and stay within ecological limits while the international system leaves them structurally dependent on the export of environmentally taxing resources. Achieving true climate justice therefore also requires rich countries to give up their currency hegemony, consume vastly less, and stop outsourcing emissions.