UKEU

18 February 2026

To reach net zero by 2050, the EU’s investment efforts are focused on two main areas: renewable energy and energy efficiency. The urgency for action has increased immensely given the current energy crisis. While the overall costs of green technologies have been decreasing and the scale of investments has been accelerating, the sudden and successive interest rate increases threaten to have a negative impact on the cost and the speed of the green transition. Only targeted monetary and fiscal interventions can counter the effects of rising rates and a deteriorating investment environment.

In October 2022, inflation in the euro area was 10.7%, with 66.7% driven by energy and food prices. High imported energy prices and Europe’s overall dependency on fossil fuels (representing 75% of its energy mix) are exactly what is making the job of the central bank that much harder. Even the European Central Bank (ECB) recognises that with less consumption of fossil fuels, the share of energy in inflation will likely go down. However, in the face of ever higher inflation numbers month after month, the ECB feels compelled to do what they think is their only option, namely increase interest rates. They implemented a 50-basis-point hike in July, then 75 basis points in September, another 75 basis points in October and a further increase is expected in December 2022, with more likely in 2023.

Rate hikes are a blunt tool that will not solve the problem of supply-driven fossilflation. Instead, it is likely to have unintended negative effects on the cost and the speed of the green transition, and most notably on the roll-out of energy efficiency and renewable energy.

Renewable energy investments in the EU, including solar, on/offshore wind, hydro and biomass, constituted €52.9 billion in 2019; that is one-third of all investment in power generation, with the remaining being fossil fuel and nuclear. In the last decade, the EU has made great strides in expanding renewables, partly due to attractive financing conditions, low interest rates and generous subsidy schemes.

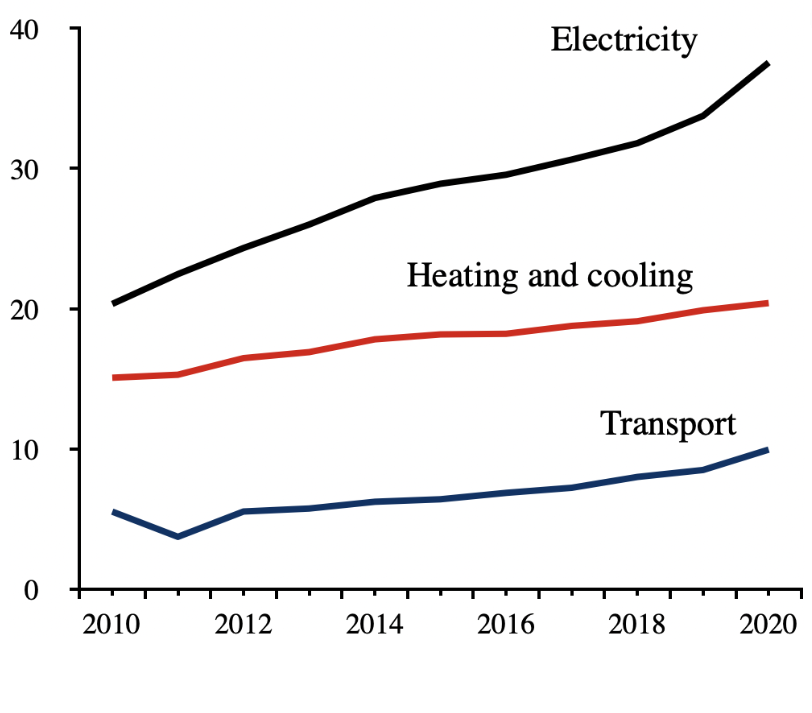

Figure 1. Share of energy from renewable sources, %

Source: Eurostat, nrg_ind_ren.

The cost of generation, measured by the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE), for solar and wind has been drastically falling, becoming even lower than gas and nuclear power generation in several regions around the world, including Europe. According to IRENA, in the last 10 years, LCOE for onshore wind decreased by 68%, offshore wind by 60% and solar PV by 88%.

Admittedly, the biggest bottlenecks in renewable energy projects are not on the financing side, but rather on the bureaucratic side, especially with the permitting process. There are many parallel initiatives in the pipeline, including the RepowerEU plan unveiled in March, which aim to streamline and bring down the time needed to process renewable projects. However, the increase in the cost of capital resulting from tighter macroeconomic conditions does have a significant impact on the roll-out of renewable projects and their speed of implementation.

The sharp and sudden reversal in the historically low interest rates could stagnate, and even reverse, this trend of decline in LCOE. Schmidt et al. (2019) find that for Germany, rates reverting back to pre-global financial crisis levels could add up to 11% to the LCOE for solar and 25% for wind, with the financing cost accounting for up to one-third of LCOE.

Capital costs rise as macroeconomic conditions tighten

Renewable energy projects are more capital intensive, require large upfront investment and take many years to lift off while future flows are committed from the onset. As such, the total cost of capital for renewables is much more cost sensitive than that of fossil fuels. A substantial component in the cost of generation, LCOE, is determined by the weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

The WACC is essential in renewable energy investments and constitutes a higher share in the LCOE compared to fossil fuels. This cost of capital component is determined by many factors, including macroeconomic and country-specific factors, energy and financial sector–specific variables, the technology level, and company- and project-specific factors. As such, monetary policy decisions, sovereign risk perceptions at the macro level and general conditions at the financial sector level all have direct implications on the cost of capital.

In order to keep renewable energy projects sufficiently competitive against fossil fuels, it is imperative to have as low a share of WACC as possible in the LCOE.

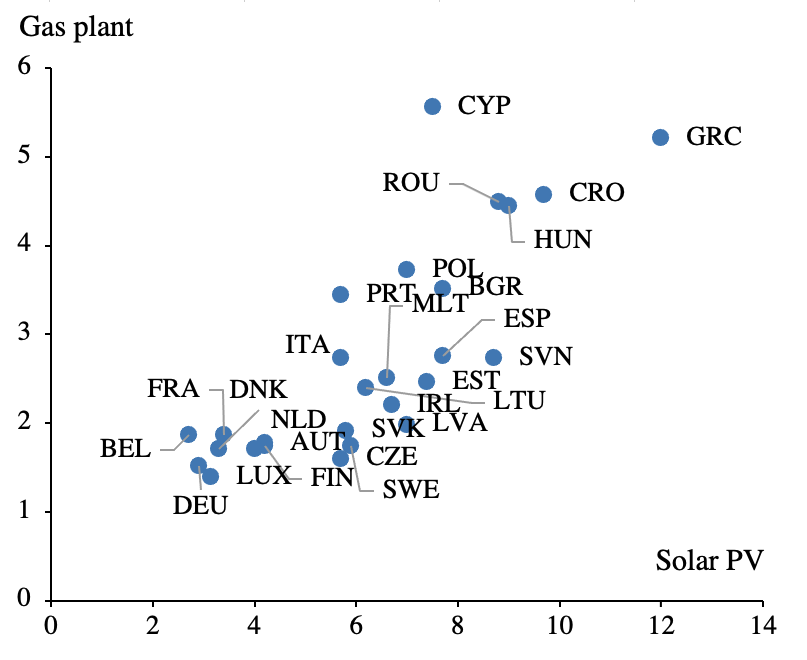

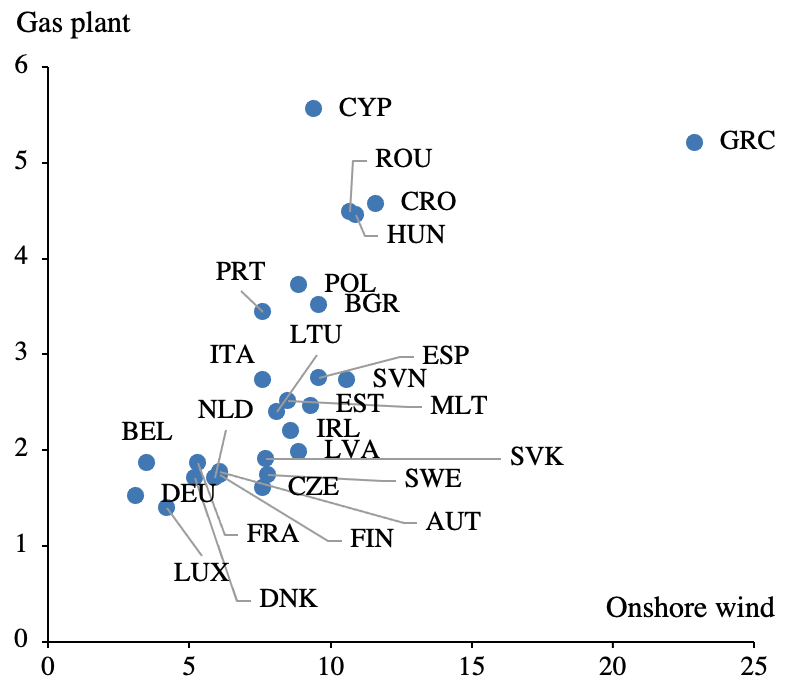

However, higher borrowing costs and investors’ increased risk perception threatens to increase the cost of capital. According to the International Energy Agency (2022), an increase of 200 basis points in the cost of capital for wind and solar can push up the overall LCOE by 20%. This effect is heterogeneous across countries, although less pronounced in more advanced countries, while having a substantial effect on less advanced and developing countries, where the cost of capital can increase as much as sixfold.

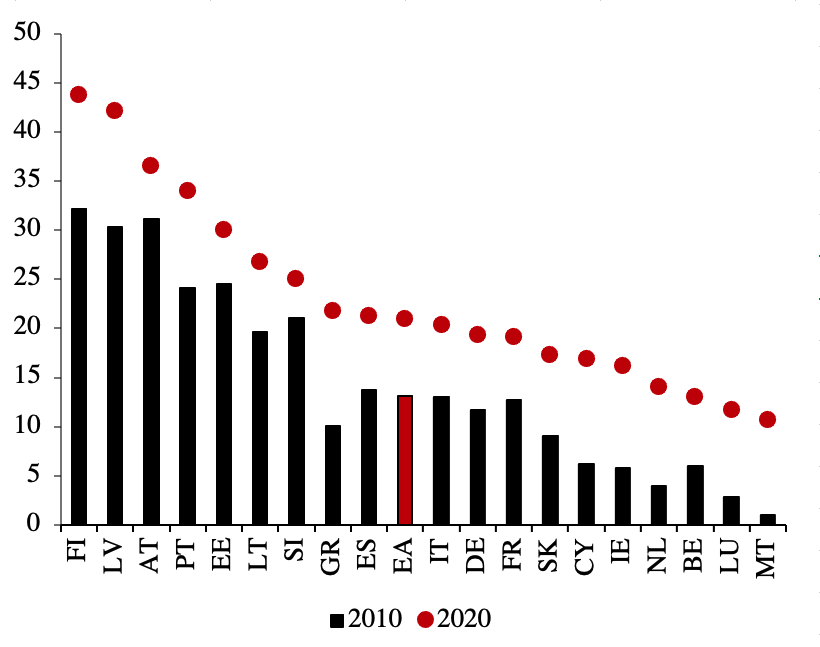

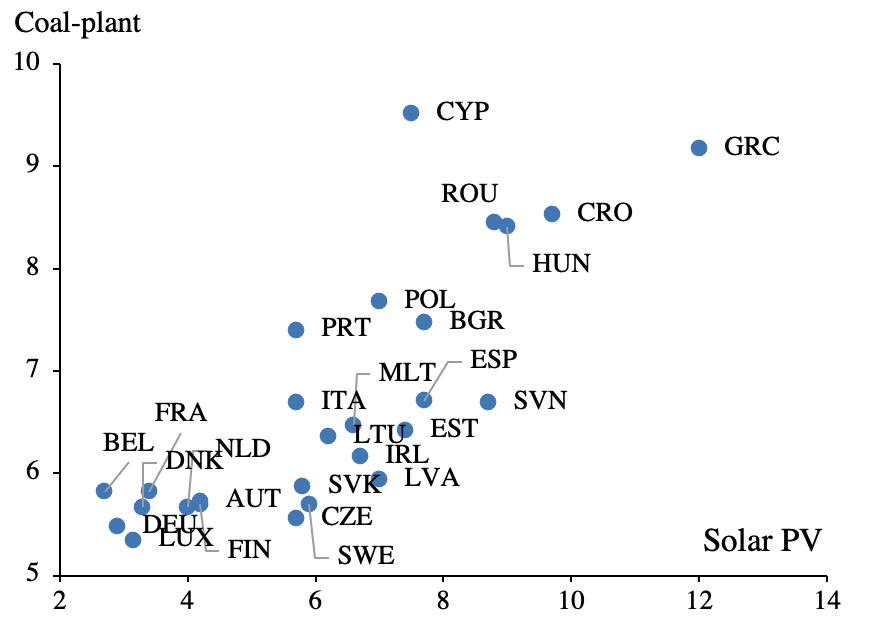

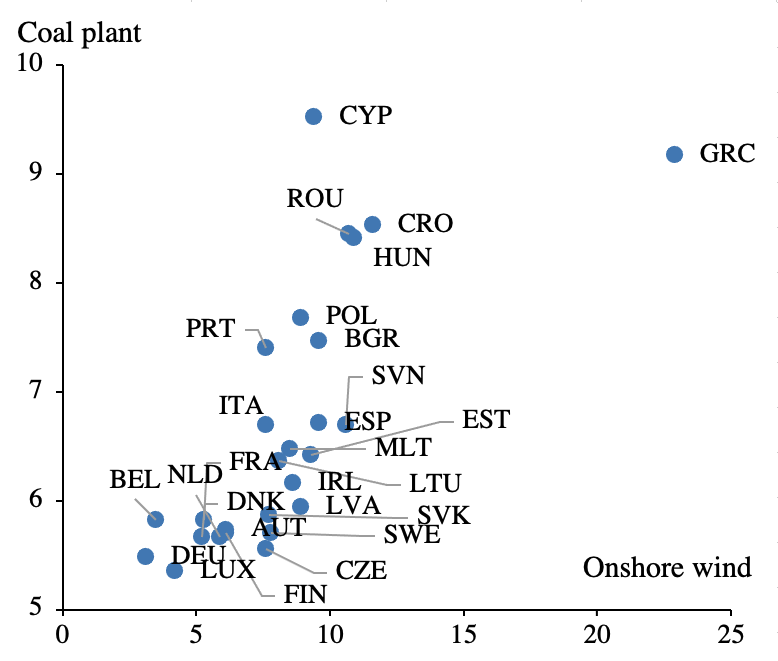

Figure 2. Weighted average cost of capital by countries and sectors, %

Source: Polzin et al (2021). Table 1.

The WACC depends on the cost of debt and the cost of equity to finance the project. Interest rate hikes matter for both types of financing.

With higher interest rates, the cost of borrowing naturally increases with investor risk perception, making it harder and more expensive to borrow the large amounts of upfront capital needed for renewable projects. As with asset financing, the firm needs to pledge a higher amount of its assets to obtain financing as risk perception rises.

The cost of equity, on the other hand, depends on the expected return on the project and the risk profile of the country, as well as being tied to macroeconomic conditions. Interest rate hikes will shrink demand, and in an environment of increased uncertainty, this could lead to a less favourable environment for equity finance.

Fragmentation along several dimensions

There is a high degree of fragmentation in terms of the cost of capital investment across different European countries. North-West European countries have the lowest WACC due to a lower cost of debt and longer loan maturity periods. Southern and Baltic countries have higher WACCs; however, some Eastern and Southern European countries (Greece and Croatia) have the highest cost of capital (Figure 2). Some countries that have a higher cost of WACC are also those that are highly reliant on imported fossil fuel.

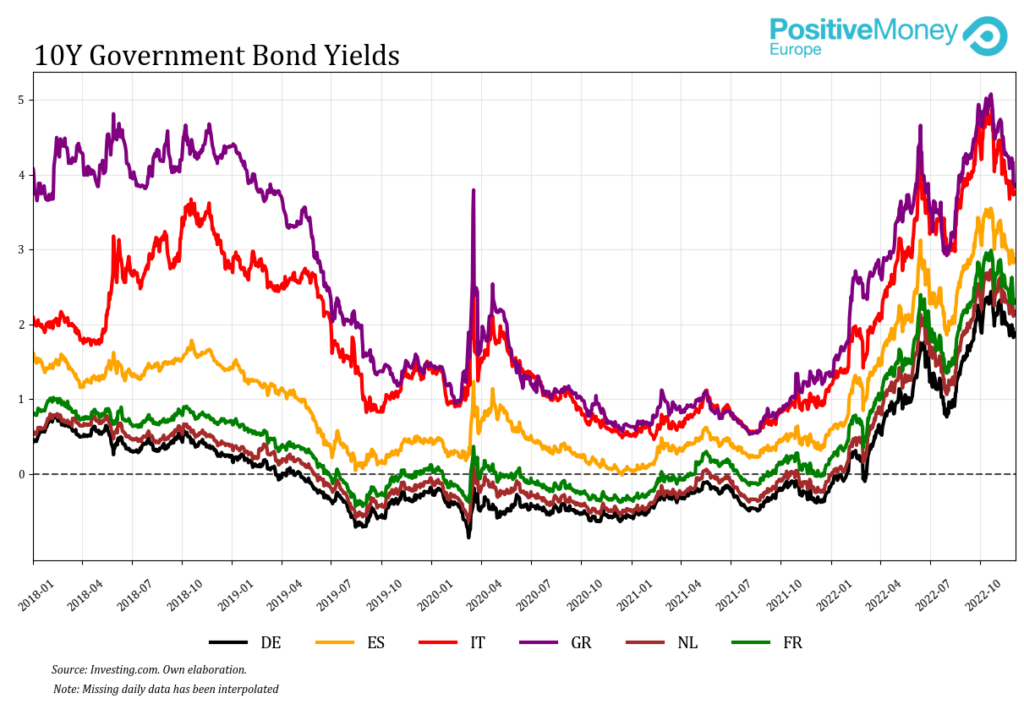

With increasing interest rates, the borrowing costs for governments are also increasing across the board for the Eurozone, further limiting fiscal capacity for long-term investment in the green transition (Figure 3). This is even more the case given the large fiscal interventions needed to tackle the energy crisis. Studies show that a percentage point increase in government bond yields leads to a 0.6–0.8 percentage point increase in WACC.

Figure 3. Rising long-term government borrowing costs.

It is also possible to observe increasing market fragmentation and concentration in the European utilities sector. With increasing margin calls, that is the collateral needed for financing, small and medium utilities cease operation with higher capital provisioning. In 2021, 7 utilities in Belgium, 2 in the Netherlands and 1 in France went bankrupt due to margin squeezes, and more bankruptcies are expected in 2022. Small and medium utilities have a higher dependency on bank financing, while larger utilities have access to both debt and equity financing. For larger utilities, while they have more access to financing, with increasing margin calls, they too might put off investment decisions in decarbonization, green technologies and their R&D.

The economics of energy efficiency investment is more fragile. According to the European Investment Bank (EIB), 65–75% of additional investment should come from final consumers investing in energy efficiency during this decade (until 2030), whereas in the subsequent decades, the investment will have to come from the energy suppliers. As such, while the investment need is constant, pacing and differentiating the needs between energy efficiency, renewables, their consumers and suppliers is a crucial factor.

To achieve the desired level of energy efficiency, it needs to be matched with equally large economies of scale. Increasing interest rates pass down to the real economy by making bank funding channels more expensive for consumers willing to increase their energy efficiency.

For instance, in the case of energy-efficient building renovations, households and businesses now face a double challenge – a higher cost of credit for renovation loans and a higher cost of materials and services because of soaring inflation.

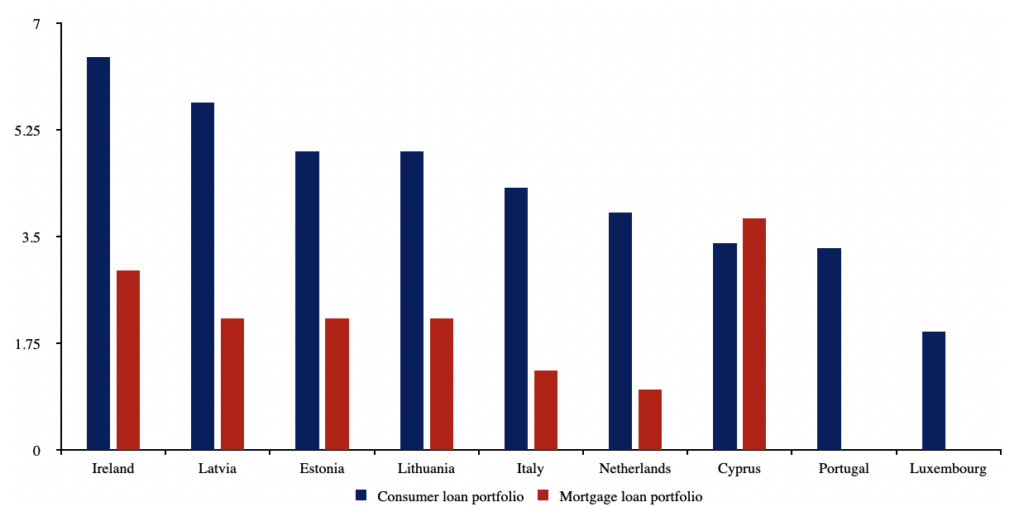

The cost of credit was already too high for renovation loans, especially if it is taken as consumer credit, since these loans are not securitised as is the case for mortgage loans. While renovation loans are less costly when taken together with a mortgage loan, it is not a widely shared practice for cost and priority reasons.

Figure 4. Interest rates on energy efficiency renovation loans as part of a consumer loan portfolio and mortgage loan portfolio, %

Source: Positive Money Europe, survey of banks, January-May 2022, sample – 14 banks.

Even before the interest rate increases, energy efficiency investments did not always pay off from their resulting energy efficiency cost savings. With credit becoming more costly, energy efficiency investment decisions will be delayed, and the scale of the challenge will not be met. This is true for building insulation, energy-efficient industrial processes, new transportation technologies and others that depend on low-cost, large-scale energy efficiency investments.

In a fossil fuel–driven inflationary environment, a speedier transition becomes a matter of the primary mandate of the ECB to keep prices stable. This point has been repeatedly stressed by President Lagarde, who has said that a ‘timely shift of our energy system towards more renewable energy [will result] in lower and more stable inflation rates’. Recently, Fabio Panetta mentioned in his speech that the green transition could have a downward effect on prices, but it depends on multiple factors, financing the transition being one of them.

Since the current crisis is a matter of both the primary and secondary mandate of the ECB, waiting for the crisis to pass and fiscal policy to drive transition is not enough; neither is waiting for carbon prices to adjust while hoping the costs of (long-term) green investment will decrease and remain competitive vis-à-vis fossil fuels. The bank should, and could, do far more beyond the pledges it made in its climate action roadmap, with speedier and more ambitious actions.

Offer a green discount rate on refinancing operations that go towards investment into renewables and energy efficiency

Since March 2020, the commercial banks in the euro area have borrowed €2.1 trillion from the ECB, with negative interest rates and without any climate and environmental conditions attached. The refinancing channel of the central bank, if directed into energy efficiency investments, entails great potential for decentralised affordable financing for transition.

By offering a green discount rate on the refinancing channel, the ECB can encourage green lending across thousands of bank branches to millions of households and businesses. Positive Money Europe has been advocating for an ECB discount rate for bank lending for energy-efficient housing renovation projects. This will incentivise households to carry out renovations in otherwise expensive financing conditions, made even more prohibitive with interest rate increases. This approach could then be translated into other segments of the bank retail and business loan portfolios.

Monetary and fiscal policy work hand in hand to decrease long-term green investment costs

Monetary policy could actively decrease the long-term investment costs for large-scale cross-border green investments in renewables. In fact, it has already been doing so through the purchase of bonds of supranational institutions, which significantly compressed their yields. The EIB is one of the seven supranationals that were eligible for the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) and represented almost 40% of the ECB’s supranational purchases from 2015 through to the onset of the pandemic. With the issuance of EU’s SURE bonds in October 2020, and NGEU bonds in June 2021, EU bonds represented three-quarters of all outstanding debt, totalling €215 billion. EU supranational debt has the potential to become a genuine safe asset, which could decrease the long-term investment costs of transition-related investments. For it to be more effective, some researchers suggest that it ought to be a more permanent fixture of the EU’s fiscal architecture.

The Eurosystem, in the meantime, can hold up to 50% of bonds issued by supranational institutions, compared to the national issuer limit of 33%. It is therefore conceivable, as we put forward previously, that the Eurosystem could announce a new programme (e.g. Supranational Purchase Programme) which would allow the purchase of more EU, EIB and other supranational bonds, focusing on keeping their interest rates very low, or even negative. This would help enormously to fund the green transition across the Eurozone, in times of rising national borrowing costs.

Rising interest rates will have negative effects on the cost and the speed of the green transition, which is badly needed to decrease the enormous upward pressure that fossil fuels are putting on inflation. Monetary policy, while not the main driver behind the wheel, can, and should, have an active role to play beyond its current pledges. The ongoing fossil fuel–induced inflation crisis is part of the climate crisis, and if active transition-oriented policies are not taken now, the job of the ECB is set to become that much harder.

The author would like to thank Simone Tagliapietra and Andrei Ilas for their expert knowledge and engaging conversations on the European energy markets, and Jordi Schröder Bosch for excellent research assistance.