EUUK

3 July 2025

As the European Central Bank (ECB) prepares for its final Governing Council meeting of 2024, policymakers are divided on the next steps. However, their differences may be less pronounced than they seem. Looking ahead to 2025, we argue that the ECB needs to revisit past discussions and reframe its approach to monetary policy.

Tomorrow, 12th December 2024, the European Central Bank (ECB) will convene for its last Governing Council meeting of the year. In the absence of any major surprise, the ECB is set to reduce its key interest rate by 25 basis points, lowering it to 3%. Cumulatively, this will amount to a 100 basis point reduction in 2024, with rate cuts having started in June. However, many believe that the current monetary policy stance is still too restrictive, posing risks to the euro area’s economic recovery.

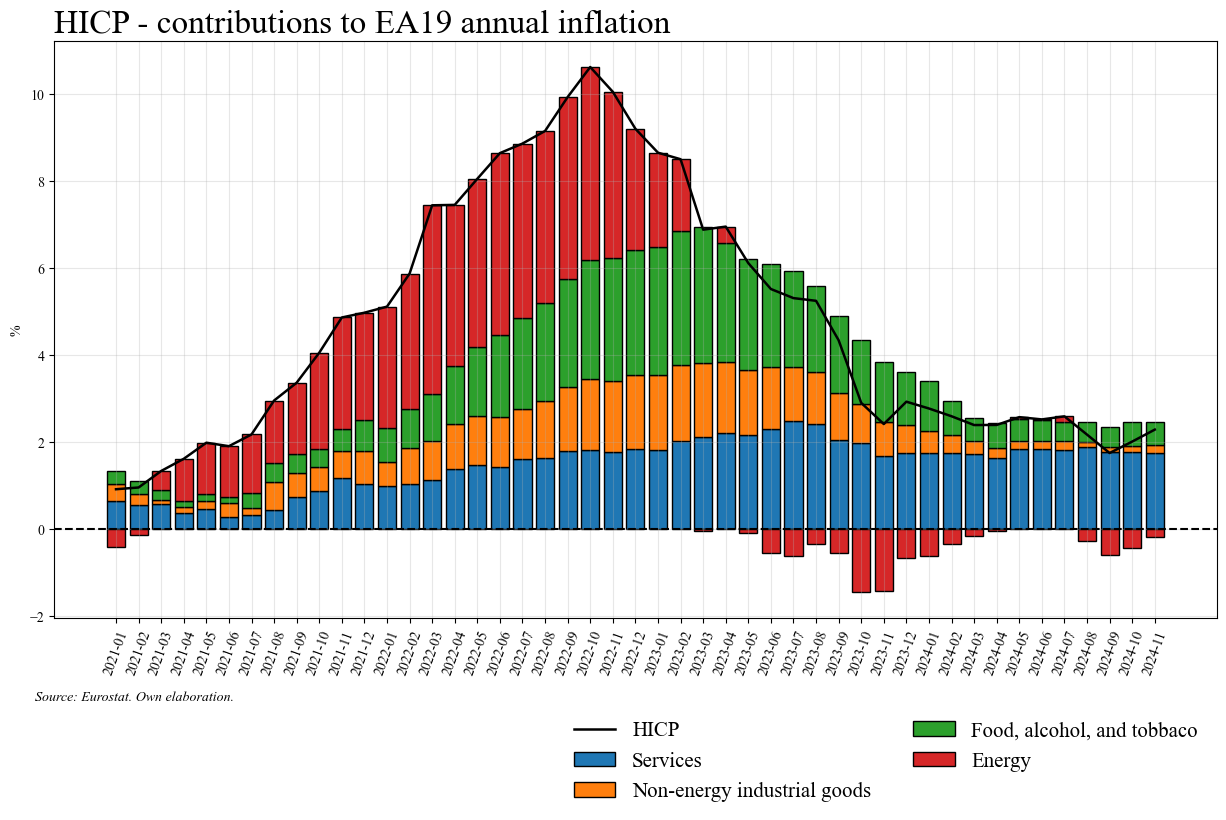

The graph below shows how inflation initially surged due to Covid-related supply chain disruptions and the energy crisis. What began as a spike in energy prices soon spread to other sectors of the economy. As inflation increased, rising profit margins added fuel to the fire.

Following that initial shock, inflation started decreasing gradually. At the beginning of 2024 , inflation stood at 2.8%, having fallen significantly from the double-digit levels observed in late 2022. Despite concerns from some policymakers that this “last mile of disinflation” would be particularly difficult to achieve, inflation has continued to decline smoothly throughout 2024. By November, inflation had reached 2.3%, bringing it very close to the ECB’s inflation target.

The ECB’s macroeconomic projections from September, which will be updated tomorrow, anticipate that inflation will return to its target by late 2025. However, actual inflation has been consistently undershooting these projections, which suggests that inflation is, in fact, approaching its target faster than the ECB expected.

At the same time, the situation for European manufacturers is showing no signs of improvement, with production levels still below those of 2021. There are fears that the service sector may also be joining this “doom and gloom party” soon, as survey data suggests that activity in the sector is slipping into recession.

This bleak context has created a divide amongst ECB policymakers. On one side, Bank of Italy governor Fabio Panetta and Bank of France governor François Villeroy de Galhau are arguing that the ECB needs to abandon its restrictive monetary policy stance. They argue that, given the fragile state of the euro area’s economy, the ECB must focus on sustaining the recovery phase to avoid driving inflation below target. With its average inflation target, the ECB should be as wary of undershooting as it is of overshooting.

On the other side of the debate stands Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel, who advocates for caution and a gradual approach to reducing interest rates. She cites three different reasons: high inflation in services, the possibility of new shocks taking place, and the ECB interest rates getting closer to neutral territory. The neutral rate of interest, which according to central bankers is the rate of interest at which inflation is on target, shapes much of the discussion between both camps. Schnabel places this rate at between 2-3%, while Villeroy de Galhau suggests a narrower range of 2-2.5%. These differing estimates imply different policy paths by the ECB.

However, when viewed through this lens, the divide between both camps does not seem as stark as business media portrays it. While their views on the neutral rate differ, both camps appear aligned on key principles of monetary policy. However, we believe that the shocks that we have experienced in recent years demand a rethink on how monetary policy is conducted. We feel that the shocks that we have experienced should push a re-think over and beyond these differing views on the neutral rate.

In 2022, ECB President Christine Lagarde expressed support for green targeted lending on two different occasions. As inflation took off, this support waned. Later, Schnabel mentioned in a speech that while green long-term refinancing rates may be a viable instrument, they “are not an option for the immediate future given the current need for a restrictive monetary policy”.

We never believed that the ambition to fight the climate crisis should have been put on hold due to rising inflation. Quite the opposite, as inflation was driven by fossil fuel prices, we argued that green sectors needed to be protected from interest rate hikes. In any case, with inflation falling towards its target, the ECB’s justification for postponing this crucial debate is now gone.

As gas prices climb again in the euro area, the risk of fossil fuel dependence on price stability is still evident. The ECB can do more to tame those risks than by simply raising interest rates when they have materialised. When it comes to integrating climate considerations to its policy framework, 2024 was another lost year. In 2025, as the ECB embarks on the revision of its strategy review, the ECB must leave its excuses behind and start acting on this key issue.