Grexit – Seize the Opportunity

A Grexit might never happen, but it could also be just days away. If a Grexit does happen, is it all doom and gloom, or is there a glimmer of hope? The re-establishment of the World’s oldest currency could represent a new path for monetary reform. One which is fit for purpose and designed to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

A Sovereign Money system could bring a number of benefits to Greece. Not only would it offer a better and safer banking system, but it would also give Greece a much better opportunity to recover from its on-going crisis. By not relying on bank lending and increased levels of debt to grow the economy, Sovereign Money offers the Greek people a more feasible chance of achieving prosperity in the short-term, as well as making such prosperity more sustainable over the long-term.

If the Drachma needs to be re-established, it would make little sense to base it on a debt-based monetary framework that has failed time and again throughout history. For the last three or four centuries, Europe, Asia, Latin America and North America have been subjected to pro-cyclical booms and busts, making millions unemployed and wiping out years of growth. This is largely because the monetary framework of these regions allows banks to create money in the form of deposits, every time they issue a loan.

The Eurozone and Greece specifically, is no exception to this as noted by Steve Keen:

“While Greece certainly had its own specific problems—especially with its current account—in general, its apparent boom before the crisis and the crisis itself had much the same cause as in the rest of the OECD: a private debt bubble that burst in 2008. Private debt grew rapidly before the crisis—on average by more than 10% of GDP per year.”

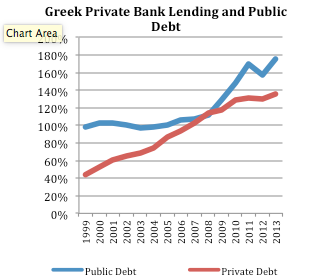

Prior to 2008, it was the private sector deficit, not the Greek public deficit that was expanding. Private banks however, were creating vast sums of money through the process of lending, for activities that did not directly contribute to a growth in private sector incomes (notice how private sector debt to GDP, or income, increased substantially from 1999 to 2008). Accordingly, the level of private debt expanded much faster than the incomes used to service such debt – until a financial crisis inevitably unfolded.

Just like in many other advanced economies, once the financial crisis struck due to banks creating too much money too quickly, the public sector had to step in, and take the private sector’s debts onto its balance sheet[i] (notice how public spending remained relatively constant until 2008, when it soared).

Monetary Reform & the Opportunity to Build a Better and Safer Banking System

A potential Grexit puts Greece in a unique position to re-create its monetary framework and withdraw the power to create money from private banks. Instead, the national bank of Greece could retain the sole prerogative of creating money, and could do so with the added benefit of creating money free of debt. This sort of Sovereign Money framework, would lead to a more stable and safer banking system.

Under the current system, the deposits that banks create – i.e. the electronic money that makes up 97% of the total stock of money – are essentially the liabilities (promises to pay) of private banks. Because we use these liabilities (or promises to pay) as our primary form of money, an irresponsible bank that has issued too many loans of poor quality must be rescued just so that the entire system of payments doesn’t collapse along with it.

In a Sovereign Money framework, the banking system could be separated so that customers have a current account and an investment account. Current account customers would hold the electronic debt free money issued by the Bank of Greece, rather than holding the liabilities of the private banks. Payments could only be made via a current account and not an investment account.

If customers wanted to borrow money, then they would have to hold an investment account.

The bank could only grant a loan to a borrower wanting to hold an investment account, if a saver had made the money available. Therefore, banks could not offer loans without having the money to begin with – they would act as pure intermediaries connecting savers to borrowers.

A separation of investment accounts and current accounts would mean that the payments system would not be jeopardised when a bank fails. Instead of having current accounts with money that is composed of promises to pay issued by banks, such accounts would hold risk-free and debt-free money issued by the state. If the customer’s bank were to fail, the money in the current account would still be safe and the customer could still access it and spend it. Customers that made their money available for lending in an investment account, would need to wait while the bank was liquidated in order to get their investment back.

Accordingly, it would not be necessary to bail out an irresponsible bank in order to protect the payment system. Banks would no longer be too big to fail. Moreover, the government would not need to offer deposit insurance. Indeed, banks would most likely be induced to lend money much more responsibly, as they would no longer be able to create it out of thin air.

A Greek Recovery?

A primary problem with the current monetary framework is that just as banks can create money through lending, money is destroyed when loans are repaid. Thus, when the rate and value of loans being repaid exceeds the rate and value of new loans being extended, the stock of money decreases. When a crisis begins to unfold, banks that have lent too much to people or businesses that can’t repay become concerned about the solvency of their own balance sheet. Consequently, they limit their lending to households and businesses, spending is diminished, and prices go down.

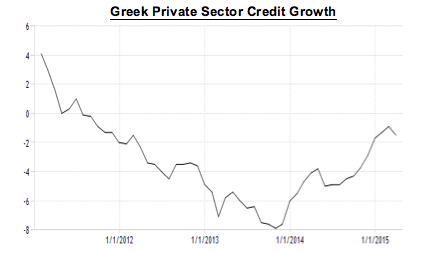

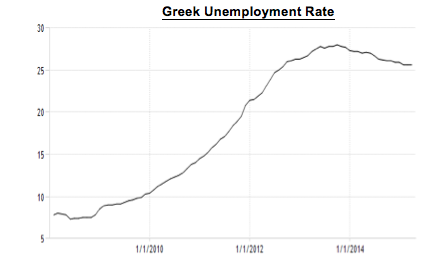

Conversely, the private sector and households start to focus on paying down their debts, and sacrifice consumption and investment spending accordingly. As spending is reduced, business profits diminish, leading to a fall in wages and increased layoffs. Higher levels of unemployment and lower wages, leads to less spending, and eventually a full-blown recession. This is a problem that has been plaguing Greece since 2011, as demonstrated by the fall in private sector credit and increased levels of unemployment.

Greece needs more spending to help grow its economy. More spending means that businesses will increase their revenues, allowing them to hire more workers and increase wages. Higher levels of employment and increased incomes, allows the private sector to spend more, leading to even more business expansion and spending, in a mutually reinforcing process.

In Greece, however, there is limited if not diminishing public sector spending. Moreover, trying to encourage foreigners to increase their spending on Greek products, effectively attempting an export led recovery, is largely out of the question because global demand is generally weak. This means that the only option left is for the private sector to increase spending. But this means that the only effective way to get the economy going again and the only way to get businesses and consumers to spend more is by encouraging banks to lend more and the private sector take on even more debt.

But if excessive levels of debt (specifically private sector borrowing) were the source of the crisis, then is this not the recipe for the next one? Moreover, it could take many years for banks to repair their balance sheets and for the private sector to be in a robust enough position to demand new loans. In sum, there is no real telling when a Greek recovery will be feasible or how long it will last until another crisis strikes.

Stimulating a Recovery with Sovereign Money

Sovereign Money also offers an opportunity for Greece to stimulate a more rapid and sustainable recovery. By creating money free of debt, and spending it directly into the real economy, Greece would have a tool that would allow for growth to take place without the private or public sector having to taking on more debt.

In a Sovereign Money system, the Bank of Greece would be solely responsible for creating new money. Instead of having money created through the process of lending, Sovereign Money would be created free of debt, just like bank notes and coins exist today[ii]. This new money would be created and added to the public budget. It could then be used in a number of ways: (1) for public spending, (2) tax cuts, or (3) direct transfers to citizens.

Sovereign Money spending means that the public and private sector would not have to take on more debt for there to be an increase in spending in the economy. The Greek economy would not be dependent on debt-based spending to fuel its recovery. This would inevitably lead to a more stable and sustainable recovery.

This also means that money could be spent into the economy even while businesses and households are paying down their existing loans. The supplementary spending by the Greek government would counter any reduction in spending caused by the private sector trying to pay down its debts. It would permit debt reduction without slowing down the economy or increasing risks of a future crisis. Thus, a Sovereign Money system would most likely induce a more rapid recovery, as an increase in spending would not be determined by the banks’ willingness to lend or by the private sector’s demand for new loans.

Most critics would suggest that a Sovereign Money system would be tantamount to giving the Greek politicians access to the national mint. This is why the administrative branches of Bank of Greece would decide how much money to create. Conversely, Greek politicians would only be permitted to decide where the newly created money would go. If inflation rose above the targeted level (usually 2%), then the Bank of Greece would slow the rate of money creation. Conversely, if there was deflation, then the Bank of Greece could speed up the rate of money creation. (For a more lengthy discussion on potential criticisms of Sovereign Money system click here).

Ultimately, Greece is in unique position to put money creation under democratic control. If a Grexit does happen, the Greek’s should seize the opportunity to implement a new monetary system that offers a safer banking system and a more rapid and sustainable recovery.

[i] Frances Coppola very aptly explains why the public sector bailout of private debts resulted in such a catastrophe for Greece specifically: “The difference between Greece and other Eurozone countries is that when it was forced to socialise private sector losses, it already had legacy debt of 100% of GDP. The fact that debt/GDP had been that high since 1993 was not the point. Seeing Greece’s debt/gdp soaring, frightened by papers such as this from Reinhart & Rogoff suggesting that high debt/gdp was economically disastrous and angered by the disclosure that Greece’s fiscal position was far worse than they had been led to believe, investors ran for the hills, causing Greece’s borrowing costs to spike and creating a real risk of default. Their behaviour brought about the very situation that they feared.” http://coppolacomment.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/greeces-real-problem.html.

[ii] When new money would be created, the Greek Treasury would issue a certain amount of ‘perpetual zero-coupon bonds’. These would be interest free and would never need to be repaid. The Bank of Greece would then purchase these bonds by crediting the Treasury account with new Drachmas. So that the Bank of Greece’s balance sheet would balance out, the newly created money would appear as a liability of the Bank of Greece and an asset of the Greek treasury. The bonds would be an asset to the Bank of Greece and a liability of the Greek treasury.