UKEU

18 February 2026

Securitisation is a word that’s been popping up a lot lately in European policy discussions — but what does it actually mean? And why should you care?

Since the release of the Letta and Draghi reports earlier this year, policymakers are looking again at securitisation as a tool to finance Europe’s economy and especially the green and digital transitions. In June 2025, the European Commission made proposals to revive securitisation in Europe. Supporters claim it could unlock new investment and strengthen the EU’s financial system. But for many, securitisation still brings back bad memories of the 2008 financial crisis.

At Positive Money Europe, we believe the public must understand how this financial tool works. In this first of two blogs on the subject, we’ll walk you through the basics of securitisation — what it is, how it works, and why it can be both risky and potentially useful.

Securitisation is a financial process through which banks and other lenders bundle together loans and transform them into tradeable financial products that investors can buy.

Here’s how it works:

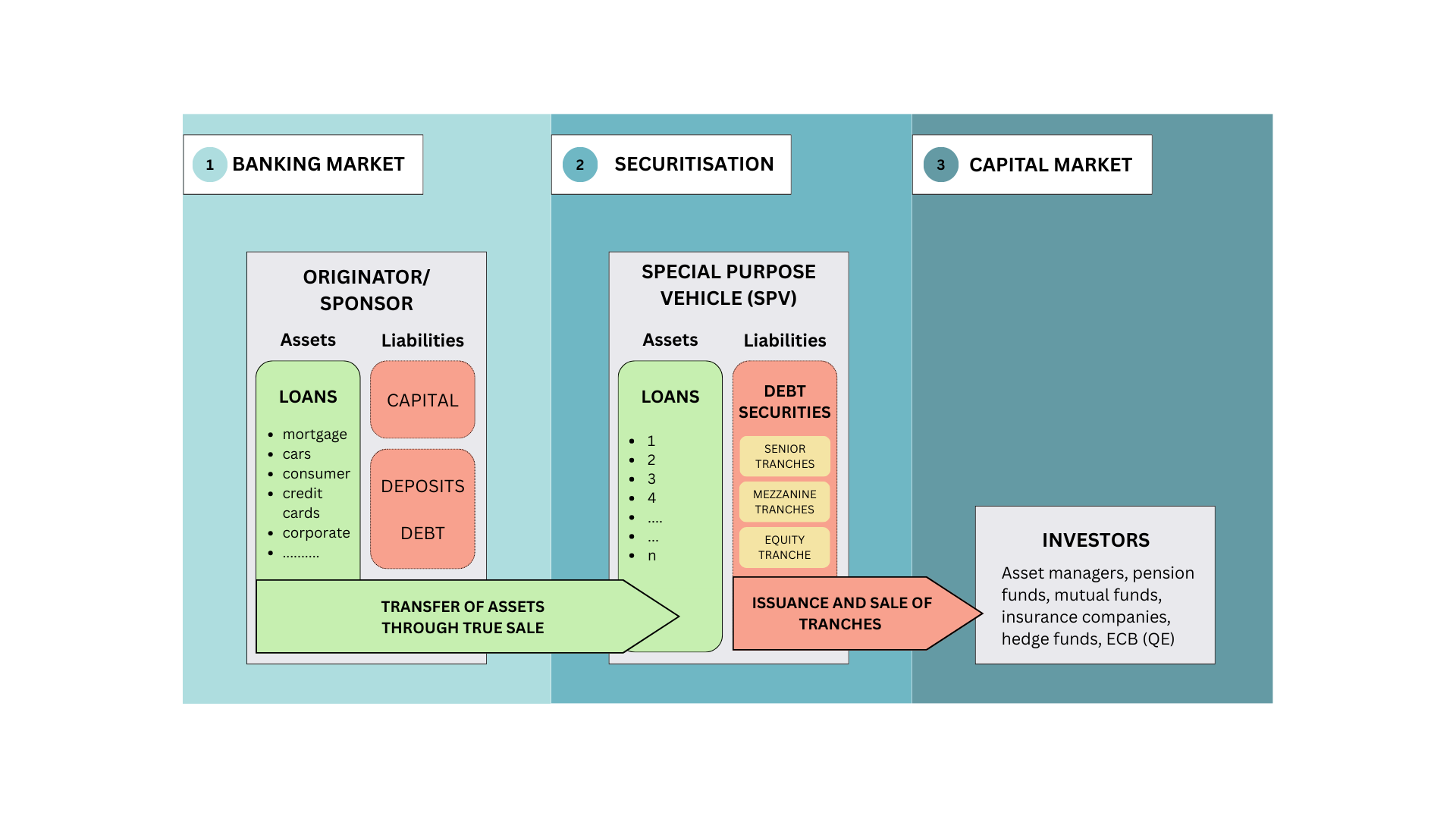

A bank makes loans to people or businesses.

Instead of keeping those loans on its books, the bank sells them to a specially created company, called a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV).

The SPV bundles these loans together and issues securities i.e. bonds backed by the loan repayments.

Investors buy these securities, and get paid from the money that borrowers repay over time.

These securities are usually structured in different layers, or ‘tranches’, with varying levels of risk and return. Securitisation can be either used to fund the lender or free-up capital on the lender’s balance sheet. However, securitisation gained a controversial reputation during the 2008 financial crisis, when those securitised products amplified the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis. Why? Because many of the securities were far too complex, opaque, and risky — and regulators weren’t watching closely enough.

As part of their regular activity, banks provide different types of loans — such as real estate, consumer, car, student, or business loans — to their customers, whether they are individuals or companies.

To fund (or refinance) these loans, banks have several options. They can:

Borrow from the central bank (like the European Central Bank),

Use customer deposits,

Or issue bonds like securitisation.

In a securitisation, the bank (called the "originator" because it created the original loans) sells a portfolio of those loans to a separate legal entity called a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). This SPV is set up specifically to buy the loans and raise money by issuing securities to investors.

This process transforms the original loans — which are private contracts and not easily tradable — into bonds i.e. negotiable financial instruments, meaning they can be bought and sold on the financial markets.

When a bank transfers loans to a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), it's called a True Sale, meaning the loans are fully sold to the SPV. This is different from a Covered Bond, where the bank still owns the loans and simply uses them as collateral. For the bank’s clients, this transfer is completely transparent. Borrowers continue to repay their loans — principal and interest — directly to the bank, which then passes these payments on to the SPV. The relationship between the bank and its clients doesn’t change because of securitisation. Securitisation is considered "collateralised" because the loans themselves act as a guarantee for the investors who buy securities backed by these loans.

As the SPV is buying assets and holding them for the benefit of the investors, the SPV is legally insulated from the originator’s bankruptcy or other credit events. If the originator is defaulting, the SPV is still receiving interest and reimbursement from borrowers so that the SPV can pay interest and reimburse nominal to investors. Without this principle of ‘Bankruptcy Remoteness’, exogenous events not related to the portfolio could result in losses for investors.

When the securitisation transaction is set up, investors receive detailed information about the loan portfolio — such as the total amount, interest rates, and maturities — except for borrowers’ names, which are kept confidential due to banking secrecy. Investors also have visibility on the expected cash flows that the SPV will receive over time (from loan repayments). Because investors buy these securities with full knowledge of the risks and details, they cannot make claims against the originating bank if something goes wrong. This is known as Non-Recourse Financing, meaning the risk lies with the investor, not the bank that sold the loans.

All the cash flows generated by the loans — both interest and principal repayments — are transferred to the SPV. This is called the Pass-Through Principle. The SPV then uses these cash flows to make regular payments to investors, including interest (called coupons) and repayments of the original amount invested (principal). These payments are made based on the order of priority, known as the seniority rank: investors with higher seniority are paid first. Even though the loans have been sold, the bank continues to manage the relationship with the borrowers.

To finance the loans purchased from the bank, the SPV divides the portfolio into different pieces called tranches, which are like slices of a pie. Each tranche is sold to investors as a bond — and each has a different level of risk and return.

Senior tranches are the safest. Investors in this tranche get paid first and are protected from losses unless the loans perform very badly. Because they’re safer, they have a good rating (usually AAA/Aaa) and offer lower returns.

Mezzanine tranches sit in the middle (if issued). They offer more risk and slightly higher returns.

Equity tranches are the riskiest. These investors get paid last, only after the others have been paid. But because they’re taking on more risk, they earn higher returns — sometimes 8–15%.

If some loans in the bundle stop being repaid (i.e. borrowers default), losses are absorbed by the riskiest tranches first. This system of “protecting” the safer tranches is called credit enhancement and is a defining feature of securitisation.

The securitisation process can be used to securitise any type of loan or receivable. In reality, there is a market consensus for certain types of loans that an originator can securitise. There are two main kinds of securitisation, depending on the type and number of loans in the bundle:

Asset-Backed Securities (ABS i.e. securities backed by assets: These involve lots of smaller loans — thousands of mortgages, consumer loans, credit cards, or car loans. They're called “granular” because of how many different borrowers are included. One common example is RMBS (Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities).

Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs) i.e. obligations collateralised by debt: These usually involve fewer, larger loans or bonds, like loans to medium or large companies. A popular type is the Collateralised Loan Obligation (CLO), where assets are either Leveraged loans or Mid cap/Large cap loans.

Securitisation serves two main purposes:

Most of the time, banks use securitisation to get better funding conditions than borrowing money in other ways. Senior tranches, which are rated very highly (AAA), are especially attractive for some investors that are looking for safe assets.

Banks are required to hold a certain amount of capital to protect against the risk of loan defaults. If they can transfer some of this risk to investors, they can free-up capital and use it to finance more loans. To do this, they must sell the riskier tranches of the portfolio through a process called Significant Risk Transfer (SRT). In these cases, banks keep the safer senior tranches and transfer the junior ones to other investors. This is especially helpful for costly loans like corporate lending, which carry heavier regulatory capital requirements.

Even then, banks are required to keep at least 5% of the risk on their books (retention regulation) to keep skin in the game. In practice, for funding transactions, they often keep even more and the riskiest part (the equity tranche) could represent up to 15% of the liabilities — because they know their customers and believe in their loan underwriting.

Not all investors are the same. Regulated institutions — like pension funds, insurance companies or other banks — must hold capital to cover the risks of the investments they make, including securitisations. The amount of capital they need depends on the riskiness of the tranche they hold.

Senior tranches are safer, so they require less capital to back them.

Junior tranches are riskier and require more capital — often too much for traditional investors to justify.

That’s why the riskiest tranches, especially equity, are usually bought by unregulated investors like hedge funds, who aren’t subject to the same capital rules and are more comfortable with higher-risk, higher-return investments.

The European Central Bank (ECB) plays a key role too. When lending money to banks (called MRO - Main Refinancing Operation) the ECB can accept securitised products as collateral but only if they meet strict criteria. Eligibility criteria for ABS is listed in the Eurosystem collateral framework. The ECB only accepts the safest, most transparent ABS (known as STS – Simple, Transparent and Standardised). It avoids CLOs, CMBS or junior tranches.

During the Quantitative Easing period, the ECB bought securitised products to inject money into the economy — but again, only the safest ones.

Securitisation isn't inherently bad. At its best, it can help banks to do more lending, but it also plays a role in shaping our financial system — how risk is distributed, who profits, and who bears the losses when things go wrong. History has shown us, for example during the 2008 financial crisis, that when securitisation goes wrong, it can threaten the entire financial system.

That’s why it’s important to make sure that these tools are used responsibly. In our next blog, we will explore the EU proposals and how securitisation could be made to work for people and the planet, rather than against them.