How do Banks Become Insolvent?

How do banks become insolvent and the importance of deposit insurance

If banks can create money, then how do they become insolvent? After all surely they can just create more money to cover their losses? In what follows it will help to have an understanding of how banks make loans and the differences between the type of money created by the central bank, and money created by commercial (or ‘high-street’) banks.

Insolvency can be defined as the inability to pay ones debts. This usually happens for one of two reasons. Firstly, for some reason the bank may end up owing more than it owns or is owed. In accounting terminology, this means its assets are worth less than its liabilities.

Secondly, a bank may become insolvent if it cannot pay its debts as they fall due, even though its assets may be worth more than its liabilities. This is known as cash flow insolvency, or a ‘lack of liquidity’.

Normal insolvency

The following example shows how a bank can become insolvent due customers defaulting on their loans.

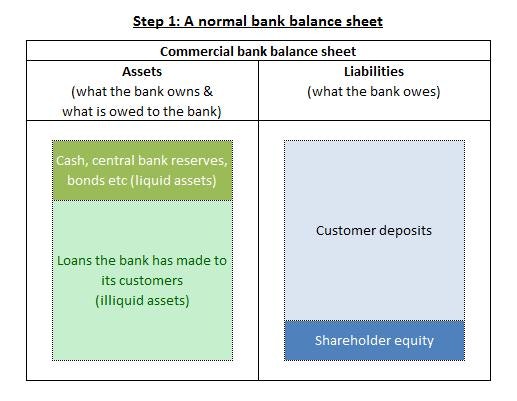

Step 1: Initially the bank is in a financially healthy position as shown by the simplified balance sheet below. In this balance sheet, the assets are larger than its liabilities, which means that there is a larger buffer of ‘shareholder equity’ (shown on the right).

Shareholder equity is simply the gap between total assets and total liabilities that are owed to non-shareholders. It can be calculated by asking, “If we sold all the assets of the bank, and used the proceeds to pay off all the liabilities, what would be left over for the shareholders?”. In other words:

Assets – Liabilities = Shareholder Equity.

In the situation shown above, the shareholder equity is positive, and the bank is solvent (its assets are greater than its liabilities).

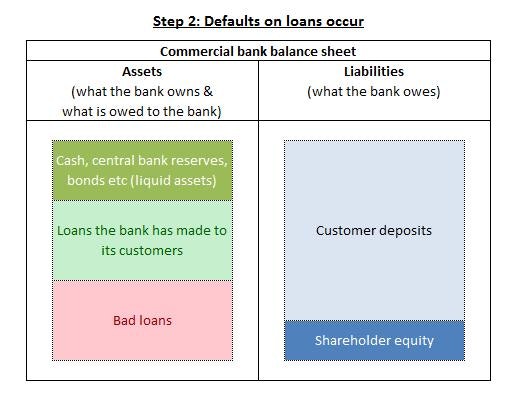

Step 2: Some of the customers the bank has granted loans to default on their loans. Initially this is not a problem – the bank can absorb loan defaults up to the value of its shareholder equity without depositors suffering any losses (although the shareholders will lose the value of their equity). However, suppose that more and more of the banks’ borrowers either tell the bank that they are no longer able to repay their loans, or simply fail to pay on time for a number of months. The bank may now decide that these loans are ‘under-performing’ or completely worthless and would then ‘write down’ the loans, by giving them a new value, which may even be zero (if the bank does not expect to get any money back from the borrowers).

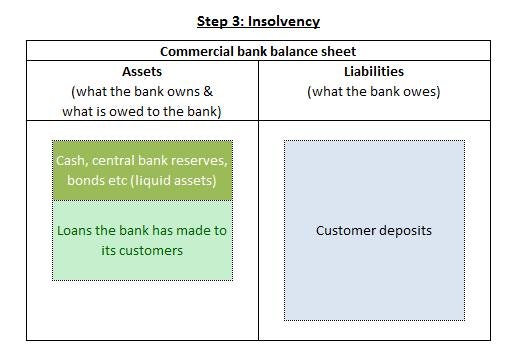

Step 3: If it becomes certain that the bad loans won’t be repaid, they can be removed from the balance sheet, as shown in the updated balance sheet below.

Now, with the bad loans having wiped out the shareholders equity, the assets of the bank are now worth less than its liabilities. This means that even if the bank sold all its assets, it would still be unable to repay all its depositors. The bank is now insolvent. To see the different scenarios that may occur next click here, or keep reading to discover how a bank may become insolvent as a result of a bank run.

Cash flow insolvency / becoming ‘illiquid’

The following example shows how a bank can become insolvent due to a bank run.

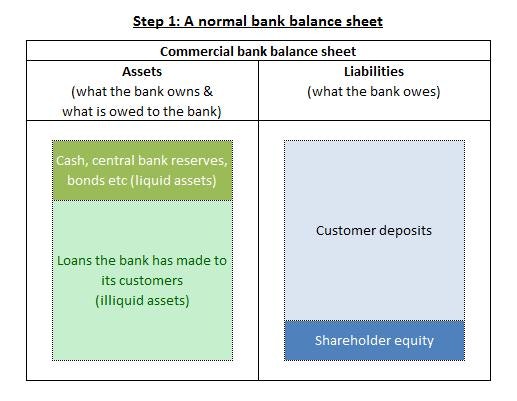

Step 1: Initially the bank is in a financially healthy position as shown by its balance sheet – its assets are worth more than its liabilities. Even if some customers do default on their loans, there is a large buffer of shareholder equity to protect depositors from any losses.

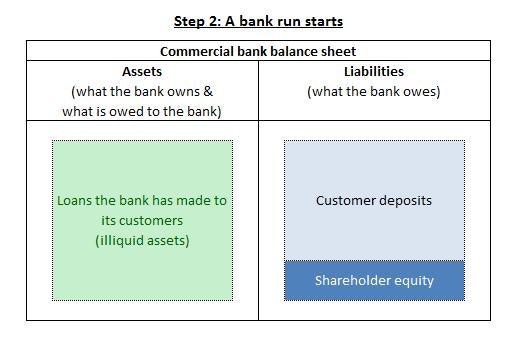

Step 2: For whatever reason (perhaps due to a panic caused by some news) people start to withdraw their money from the bank. Customers can request cash withdrawals, or can ask the banks to make a transfer on their behalf to other banks. Banks hold a small amount of physical cash, relative to their total deposits, so this can quickly run out. They also hold an amount of reserves at the central bank, which can be electronically paid across to other banks to ‘settle’ a customer’s electronic transfer.

The effect of these cash or electronic transfers away from the bank is to simultaneously reduce the bank’s liquid assets and its liabilities (in the form of customer deposits). These withdrawals can continue until the bank runs out of cash and central bank reserves.

At this point, the bank may have some bonds, shares etc, which it will be able to sell quickly to raise additional cash and central bank reserves, in order to continue repaying customers. However, once these ‘liquid assets’ have been depleted, the bank will no longer be able to meet the demand for withdrawals. It can no longer make cash or electronic payments on behalf of its customers:

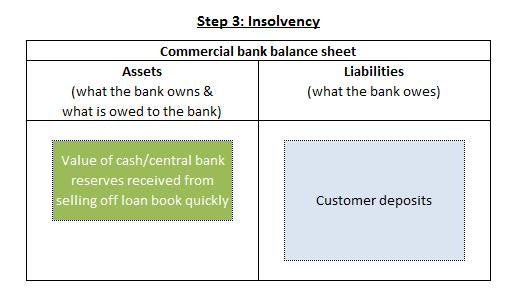

At this point the bank is still technically solvent; however, it will be unable to facilitate any further withdrawals as it has literally run out of cash (and cash’s electronic equivalent, central bank reserves). If the bank is unable to borrow additional cash or reserves from other banks or the Bank of England, the only way left for it to raise funds will be to sell off its illiquid assets, i.e. its loan book.

Herein lies the problem. The bank needs cash or central bank reserves quickly (i.e. today). But any bank or investor considering buying it’s illiquid assets is going to want to know about the quality of those assets (will the loans actually be repaid?). It takes time – weeks or even months – to go through millions or billions of pounds-worth of loans to assess their quality. If the bank really has to sell in a hurry, the only way to convince the current buyer to buy a collection of assets that the buyer hasn’t been able to asses is to offer a significant discount. The illiquid bank will likely be forced to settle for a fraction of its true worth.

For example, a bank may value its loan book at £1 billion. However, it might only receive £800 million if it’s forced to sell quickly. If share holder equity is less than £200 million then this will make the bank insolvent:

After insolvency and the need for deposit insurance

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kd0cCp3jAqk

For a bank, being insolvent means it cannot repay its depositors, because its liabilities are greater than its assets. The effect that a bank has if it becomes insolvent depends upon the availability of deposit insurance.

In a country without deposit insurance an insolvent bank would not be able to repay people deposits in full. In the event of an insolvency depositors would have to queue up with other bank creditors to reclaim whatever money they could from the bank. So for every £1.00 the bank owed to customers it might only pay 90p or even less.

However, this is not the end of the story. The failure of one bank could lead people to worry about the financial position of other banks. Furthermore the insolvent bank would have certainly owed money to other banks, as would its customers. This can lead to a domino effect – a bankruptcy at one bank can lead to a ‘cascade’ of defaults, bank runs and insolvencies as people panic.

One way a bank can raise funds quickly in the event of a bank run is to sell assets. However, if ‘distressed selling’ occurs on a large enough scale it may lead to a debt deflation. The American economist Irving Fisher saw debt deflation as one of the key causes of the great depression. In Fishers formulation, the process proceeds as follows:

(1) Debt liquidation leads to distress setting and to (2) Contraction of deposit currency, as bank loans are paid off, and to a slowing down of velocity of circulation … cause[ing] (3) A fall in the level of prices … [as a result] there must be (4) A still greater fall in the net worths of business, precipitating bankruptcies and (5) A like fall in profits, which in a “capitalistic,” that is, a private-profit society, leads the concerns which are running at a loss to make (6) A reduction in output, in trade and in employment of labor … lead[ing] to (7) Pessimism and loss of confidence, which in turn lead to (8) Hoarding and slowing down still more the velocity of circulation. The above eight changes cause (9) Complicated disturbances in the rates of interest…

Because of the negative impacts of debt deflation governments seek to avoid it at all costs. One way they may do so is by providing deposit insurance to depositors. The first system of deposit insurance was established in America in response to the Great depression. Its purpose was to prevent the bank runs that contributed to the Depression from ever happening again. In a country with deposit insurance an insolvent bank will have its assets seized and sold off. The depositors are then fully reimbursed using the funds raised, with the taxpayer making up any shortfall. The idea is that because depositors know their money is safe no matter what, they will not bother withdrawing their deposits if there is a panic. This is intended to prevent bank runs spreading and the mass sell off of assets that may spark a debt deflation.

The problem with deposit insurance.

In a system without deposit insurance depositors have a big incentive to monitor their banks behaviour, to ensure they do not act in a manner which may endanger their solvency. (If the government didn’t promise to repay your money in the case that your bank fails, would you not be a little more concerned about how the bank uses your money?). In a system with deposit insurance this incentive is removed. Economists call this moral hazard. Moral hazard is when the provision of insurance changes the behaviour of those who receive the insurance in a undesirable way. For example, if you have contents insurance on your house you may be less careful about securing it against burglary than you otherwise might be.

Deposit insurance removes depositors incentive to monitor bank lending decisions because they are guaranteed to receive their money back. Instead, depositors are incentivised by the interest rate offered. Of course, those banks offering the highest interest rate will be those taking the greatest risks, and so banks are incentivised to finance the highest risk, highest return projects.

While higher interest rates may seem to benefit depositors due to higher returns (but not taxpayers – due to greater risks leading to more financial crisis and bailouts) it reality they do not. Instead of offering a higher rate of interest the private bank can offer a lower rate, because the deposit is risk free. This results in a subsidy to the banking sector – the value of which reached over £100bn in 2008.

So despite the fact that deposit insurance is intended to increase the stability of the banking system by preventing bank runs it may in fact make it more dangerous by encouraging risky behaviour from banks:

The U.S. Savings & Loan crisis of the 1980s has been widely attributed to the moral hazard created by a combination of generous deposit insurance, financial liberalization, and regulatory failure… Thus, according to economic theory, while deposit insurance may increase bank stability by reducing self-fulfilling or information-driven depositor runs, it may decrease bank stability by encouraging risk-taking on the part of banks.

Demirgüç-Kunt and Detragiache go on to empirically test whether deposit insurance makes financial crisis more or less likely:

Having analyzed empirical evidence for a large panel of countries for 1980-97, this study finds that explicit deposit insurance tends to be detrimental to bank stability, the more so where bank interest rates have been deregulated and where the institutional environment is weak. We interpret the latter result to mean that, where institutions are good it is more likely that an effective system of prudential regulation and supervision is in place to offset the lack of market discipline created by deposit insurance.

For more details see:

Where Does Money Come From?

A guide to the UK Monetary and Banking System

Written By: Josh Ryan-Collins, Tony Greenham, Richard Werner & Andrew Jackson