How Central Banks Create Money

Creating Central Bank Reserves

Let’s start by seeing how the Bank of England creates the electronic money that banks use to make payments to other banks. Central bank reserves are one of the three types of money, and are created by the central bank in order to facilitate payments between commercial banks.

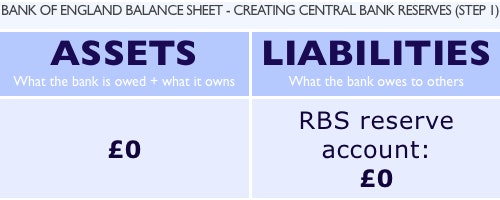

In the following example we will show how the central bank creates central bank reserves for use by a commercial bank, in this case RBS. Initially the bank of England’s balance sheet appears as so (this is a simplified example where we’ve ignored everything except this particular transaction):

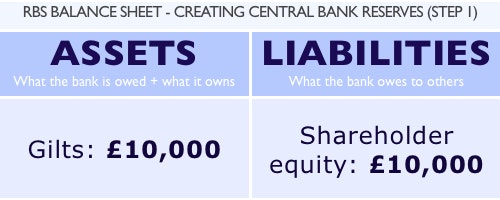

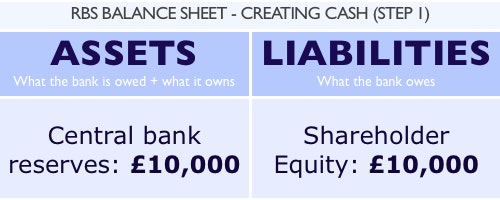

RBS’s shareholders have put up £10,000 of their own money which has been invested in government bonds. So RBS’s balance sheet is:

As a customer of the central bank, RBS contacts the central bank and informs them that they would like £10,000 in central bank reserves.

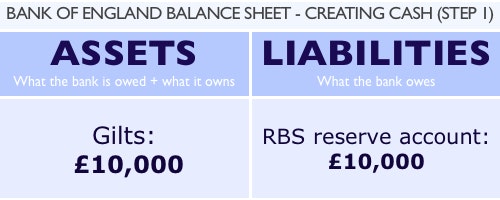

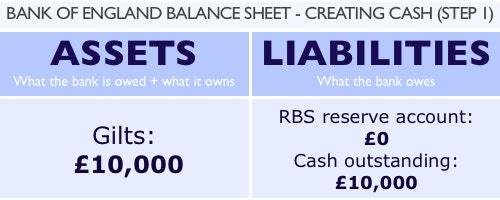

For the purposes of this example it will be assumed that the Bank of England purchases the gilts from RBS outright. Once the sale is completed the Bank of England has gained £10,000 of gilts, but it now has a liability to RBS of £10,000, which represents the balance of RBS’s reserve account, as so:

The Bank of England’s balance sheet has ‘expanded’ by £10,000, and £10,000 of new central bank reserves have been created, effectively out of nothing, in order to pay for the £10,000 in gilts.

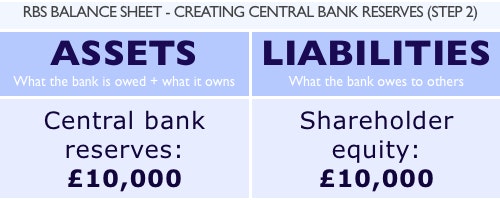

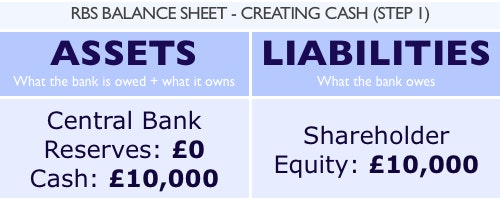

However, from the point of view of RBS’s balance sheet it has simply swapped £10,000 in gilts for £10,000 in reserves:

RBS’s balance sheet has not expanded at all; it has simply swapped one asset for another, without affecting its liabilities. RBS can now use these reserves to make payments to other banks, as described below.

N.B. The central bank could alternatively lend RBS the reserves (in this case the assets side of the central bank’s balance sheet would show a £10,000 loan to RBS rather than £10,000 of gilts and the RBS balance sheet would show the new reserves as an additional asset on top of its holdings of gilts, and its obligation to repay the loan as an additional £10,000 liability).

Sale and repurchase agreements (Repos)

However, the standard method by which the Bank of England creates reserves is through what is known as a sale and repurchase agreement (a repo), which is similar in concept to a collateralised loan. Essentially RBS sells an interest in an asset to the central bank (usually a gilt) in exchange for central bank reserves, while agreeing to repurchase its interest in said asset for a specific (higher) price on a specific (future) date. If the repurchase price is 10% higher than the purchase price (i.e. 10% higher than £10,000 = £11,000) then the ‘repo rate’ is said to be 10%. A repo transaction has different accounting rules from an outright sale. The Bank of England balance sheet would not show the gilts as the asset balancing the reserves, but the value of the interest in the gilts (valued at the £10,000 paid, not the £11,000 promised), whilst RBS would retain the gilts on its balance sheet in addition to the central bank reserves but record as an additional liability its £10,000 obligation to complete its end of the repurchase agreement. The extra £1,000 does not appear on either balance sheet but, when paid, is recorded as revenue (profit) for the Bank of England and an expense (loss) for RBS.

You may ask where does RBS get the money to pay the repo rate? – i.e. the interest on the repo. The Bank of England actually pays a rate of interest on central bank reserves equals to the repo rate – so if RBS borrows £10,000 using a repo at 10% it must repay £10,000 plus £1,000 in interest. Prior to RBS’s repayment the Bank of England pays interest on the reserves at 10%. This gives RBS £1,000 extra reserves which it must promptly use to repay the outstanding £11,000.

Whilst this process may seem a bit of a odd, there is actually a good reason for paying interest on reserves in this manner. First, it means that banks are not penalised for holding reserves – having to borrow reserves at interest but not receiving interest on them meant that banks would be effectively charged for holding reserves. Correspondingly, it means that banks will not try to minimise their holdings of reserves. Before the Bank of England paid interest on reserves banks would attempt to hold as few as reserves as possible, which could pose a problem for settling payments.

Secondly, and most importantly by controlling the rate of interest paid on reserves, as well as the interest rate it charges banks to borrow in an emergency (it charges a premium interest rate on reserves lent through its ‘overnight lending facility’), the Bank of England creates a ‘corridor’ around its desired Policy (interest) rate. This ‘corridor’ allows it to set the interest rate at which banks lend to each other on the interbank market. For example, if the rate paid on deposits is 4%, and the rate charged on emergency lending is 6%, normally a bank will never lend reserves to another bank at a rate of interest below the rate it could receive from depositing its reserves at the Bank of England (4%), or borrow reserves from another bank at a rate of interest higher than it could borrow from the Bank of England (6%). Because of this the interest rate banks will be willing to lend reserves to each other on the interbank market will be around 5%. (However today, due to the excess reserves in the system from Quantitative Easing, most banks have too many reserves, and as a result the central bank is setting interest rates through a ‘floor’ system)

How Central Banks Create Money (as Cash)

The process by which the central bank sells cash to banks is similar to that used for reserves. Initially the Bank of England’s balance sheet appears as so:

And RBS’s balance sheet appears as:

If RBS decides it is expecting an increase in demand for cash – for example before a bank holiday weekend – then it may wish to exchange some of its (electronic) central bank reserves for (physical) cash. The process by which it does so is very simple – RBS simply exchanges £10,000 of its central bank reserves for £10,000 cash with the central bank.

The Bank of England’s liabilities change from £10,000 in RBS’s central reserve account, to £10,000 of ‘cash outstanding’. (The Bank of England records cash as a liability on its balance sheet, for historical reasons that we won’t go into here):

Meanwhile, RBS’s assets have changed from £10,000 of central bank reserves, to £10,000 in cash:

Note that neither balance sheet has expanded or contracted; it is just the nature of assets and liabilities that have changed. When the cash is worn out, damaged, or not needed anymore, the transaction is reversed and RBS simply sells back the cash to the Bank of England at face value, receiving £10,000 in central bank reserves in return.

For more details see:

Where Does Money Come From?

A guide to the UK Monetary and Banking System

Written By: Josh Ryan-Collins, Tony Greenham, Richard Werner & Andrew Jackson