Concerned about housing costs? Don’t put your faith in the ECB

In its new strategy, the ECB decided that housing costs should be better reflected in the inflation index. However, this won’t address citizens’ concerns. If there is anything the ECB can do about the rise in housing costs, it is to change the way it conducts its monetary policy.

The worry about rising housing costs

Housing costs refer to all consumer expenses associated with buying or living in a flat or house, such as the cost of shelter, utility bills and maintenance costs.

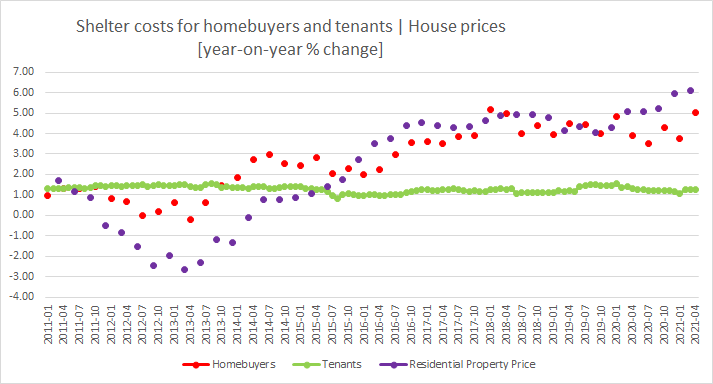

Out of all components, the cost of shelter for homebuyers has increased the most in recent years (see graph 1). This is because house prices have been on a massive upward trend. In the Eurozone, residential property prices have risen by 31% since 2010, and as much as 80% in Germany (Eurostat, 2021). The rate of increase in house prices also increased in every country in the Eurozone, especially during the pandemic (ECB, 2021).

Source: Data from Eurostat and ECB.

Note: The shelter cost of homebuyers is a subset expenditure category called “acquisition of dwellings” in the owner-occupied housing price index by Eurostat. It includes data from all 19 Eurozone countries but Greece. Tenants’ shelter costs refer to rents paid and represent the actual rentals for housing that are recorded in the HICP. Residential Property prices are the transaction values of all purchases of new and existing dwellings, regardless of whether they are for personal use or investment purposes.

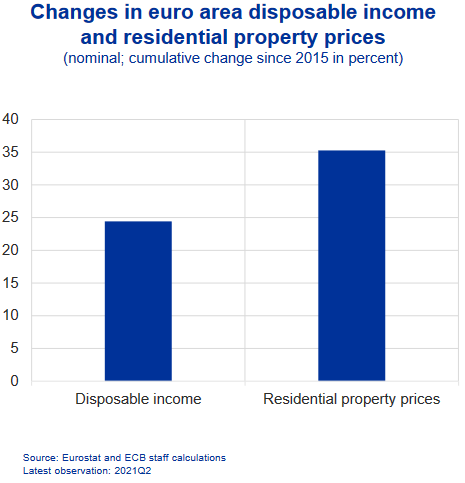

In the same period, however, the disposable income of households’ – one of the most important factors determining the ability to purchase a house or flat – has increased significantly less (see graph 2).

Graph 2

Source: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2021/html/ecb.sp211109_2_annex~c85a4a5016.en.pdf

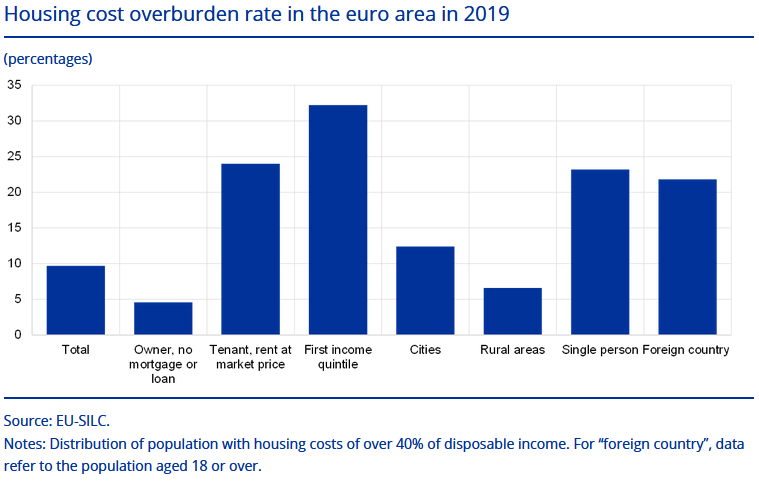

Going forward, the rate of house price growth might slow down, but prices are expected to continue to rise, at least for key Eurozone markets.(1) This might translate into rent increases as investors look to recover some of the increased purchase prices.(2) As a result, not only the expenses for homebuyers but also for tenants could increase. As many people, but especially tenants new to the market and low-income workers, are already overburdened by housing costs (see graph 3), they are concerned about the current and predicted situation (see the ECB Listens Summary).

Graph 3: Housing cost overburden rate in the euro area in 2019

So far, housing costs are neglected in the inflation calculation

Although 24% of all spending by EU citizens is on housing, it is underrepresented in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP). In the underlying consumption basket, housing costs are only weighted with 6.5%.(3) This is because only actual rents are counted as housing costs and the costs of households that have just bought their own house/flat or already living in it are being ignored. This is a remarkable omission considering that 71% of all euro area citizens live in their own house or flat. By excluding their costs, the HICP undervalues the weight of overall housing costs. This is one of the key reasons why many people do not trust the inflation data.(4)

In response to the criticism, the ECB wants to include the cost of buying a home

In July 2021, as part of the conclusions of its strategy review, the ECB reiterated a demand it had already issued in 2003: Eurostat should include the shelter costs of those buying a home in the inflation index. By applying the so-called net-acquisitions approach, Eurostat should record the cost of buying a home based on the price that households pay for that home. This approach includes an asset element because one part of the transaction price is the value of land, which, unlike durable consumption goods such as cars, can increase over time. It is not desirable to have an asset component in the consumer price index and hence the ECB asked Eurostat to eliminate the asset component from the recorded price.

The ECB framed its decision as proof that it takes citizens’ concerns seriously, with President Lagarde saying that this is the ECB “responding to the frustration of many of the Europeans that we have consulted, and that reached out to us”.

Although the ECB’s decision is welcome, if implemented (which is not expected to happen before 2026!), it would probably not allay people’s concerns about housing costs.

Why the ECB’s strategy does not address people’s housing cost concerns

In its inflation index, the ECB still ignores the shelter costs of homeowners. Their opportunity cost, i.e. the money they forgo by living in their house/flat instead of renting it out, is not captured by the net acquisition approach.

Nevertheless, the inclusion of only homebuyers’ shelter costs would lead to measured inflation rates that are marginally higher; in the case of housing booms symmetrically occurring in the euro area, significantly higher.(5) This could bring about a policy response that would not have been triggered by the old HICP.(6) But would this be effective in tackling citizens’ concerns about housing costs?

Higher measured inflation would induce an earlier and stronger contraction of monetary policy. However, it is not clear that house prices and housing costs would significantly decrease in response. The wider effects on the real economy could even mean that – relative to their income – households’ housing costs go up.

Even if interest rate hikes would bring about a decline in house prices and housing costs, it would only be the collateral effect of an engineered recession, the negative consequences of which would far outweigh the temporary relaxation in house prices. This illustrates that blunt instruments like short-term interest rates are a poor choice for tackling the cost of purchasing a house or, more generally, the cost of any specific good or service.

How to tackle housing costs

Increased housing costs can best be tackled by regulatory institutions and fiscal agencies. Based on the assumption that house prices (eventually) affect housing costs, regulators should address what has recently contributed most to house price increases: investment demand in residential buildings. The enormous financialisation of housing and its emergence as the world’s most attractive asset class has allowed house prices to accelerate. Hence, protecting housing from financial capital should be prioritised, preferably at the international level. On the national level, governments could tax the purchase of houses by investors higher than purchases of houses for personal use, phase out subsidies for homeownership and build more affordable (social) housing.

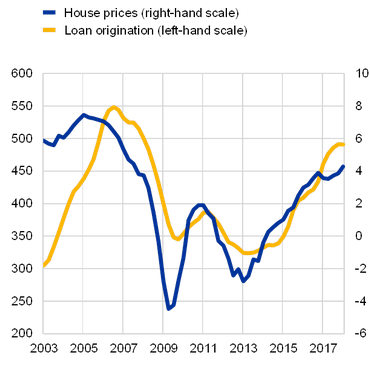

The ECB can also play its part. Although it is not solely responsible for the surge in house prices, it has contributed significantly to it in the last decades. This is mainly due to the way monetary policy currently works: it is implemented by banks and other financial market actors. Both are currently strongly biased towards driving up the price of housing. For example, approximately 74% of all bank loans to households are for the purchase of a house, and the volume of originated loans correlates well with the rise in house prices (see graph 4). The ECB is also directly involved in the mortgage market, as it holds about 15 million euros in asset-backed securities based on residential mortgages (ECB, 2021). Since a rise in house prices increases the demand for more credit, which in turn contributes to rising house prices, a vicious cycle is created.(7) By pumping money through these channels, the ECB indirectly contributes to a surge in house prices, putting upward pressure on housing costs.

Graph 4: House prices and mortgage origination in percentage changes, accumulated 12‑month flows in EUR billions

Source: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/articles/2018/html/ecb.ebart201807_02.en.html

To address rising housing costs stemming from accelerating house prices, the ECB could conduct monetary policy in a way that doesn’t rely on house price appreciation. For example, the ECB could beneficially refinance banks that lend for productive purposes and not for real estate purchases, similar to the so-called TLTROs which are already in place. Furthermore, the ECB could reduce its purchases of mortgage-backed securities to avoid channelling further money into the housing market. The ECB could also bypass banks and other financial market participants altogether by directly crediting the accounts of households and corporations. Thereby, it could direct its monetary policy to where productive activity in the economy takes place, avoiding the propping up of asset markets. In case these measures are successful and house prices decrease, the ECB could coordinate with fiscal authorities and support their financing conditions so that governments can offset any potential negative effects on aggregate demand.

Conclusion

Overall, the ECB’s decision to include the cost of buying a home in the inflation index is a welcome step that will slightly correct a long-lasting inaccuracy. But citizens should not think that this will address their concerns pertaining to housing costs. The ability to address rising housing costs should not and cannot hinge on measured inflation or the ECB’s monetary policy stance. Since the financialisation of housing is the most important reason for the surge in house prices, which translates into increased costs for homebuyers and perhaps also for tenants, governments should ensure that the function of houses/flats as living spaces is brought back into focus. Nevertheless, the ECB should also play its part and recognise that the model of implementing monetary policy by blindly throwing money at banks and financial markets badly serves people’s needs.

(1) See Battistini, 2021 and ING, 2021

(2) According to IMF staff calculations, based on a cross-country estimate of the link between nominal house price growth and CPI rent inflation, a 1 percentage point in year-on-year increase in nominal house prices in the quarter ahead is associated with a cumulative increase of 1.4 percentage point in annual rent inflation over a period of two years. The effect is estimated to persist for about three years (IMF, 2021). But there are also reasons to believe that rents won’t be much affected by house price increases. For example, Gros & Shamsfakhr (2021) find only a marginal correlation for euro area countries.

(3) For more background, see our previous blog article.

(4) An ECB paper finds that house price is one of the most important factors for perceived inflation, which is typically higher than observed inflation (see Nickel et al., 2021, p. 50).

(5) Existing studies estimate that, between 1999 and 2019, an expanded HICP would have increased average Eurozone inflation only marginally by 0.07% (Lünnemann & Wintr, 2021; Darvas & Martins, 2021). During the housing boom in 2006, it would have raised measured inflation by about 0.3 percentage points (Darvas & Martins, 2021). Since 2014, due to the enormous increase in house prices, it would have added 0.2 – 0.3 percentage points (Schnabel, 2021). It’s probable that these significant changes would be the result of the asset component within the newly augmented inflation index which Eurostat currently tries to eliminate (see Nickel et al., 2021).

(6) Note that the ECB’s new strategy makes it unlikely that the Governing Council will raise interest rates purely as a result of an inclusion of owner-occupied housing costs.

(7) Josh Ryan Collins (2021)