Historical examples of Sovereign Money Creation

Using money creation to increase aggregate demand is not a new idea. In fact it has been advocated by some of the 20th century’s most famous economists, including John Maynard Keynes, Milton Friedman and Henry Simons, amongst others. More recently, Ben Bernanke, Governor of the Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2014 recommended using such a policy in response to the Japanese deflation of the 1990s and 2000s. Several notable economists have recommended similar proposals in the wake of the 2007-08 financial crisis. Even the UK Treasury agrees that it is “possible for monetary authorities to finance fiscal deficits through the creation of money.” However, it is not just theoretically possible, there are multiple examples of governments using money creation to finance part of their deficits. In fact, up until the year 2000 in the UK the government financed a part of its deficit via money creation through an overdraft at the central bank – the ‘Ways and Means Advance’. Although the ‘Ways and Means Advance’ has some differences from Sovereign Money Creation, its use shows that creating money to finance fiscal deficits was actually normal policy before 2000.

Early history

Historically, governments often financed themselves partly through money creation. For example, during the colonial era in the United States many states created and spent paper money into circulation to aid in trade, with Pennsylvania a particularly successful example. Later both the North and South sides in the US civil war would issue paper money (which was not backed by gold) to help pay for their war efforts. More recently in New Zealand in the 1930s the central bank created new money to make a loan to the government to fund house building. Although none of these policies used the terms “Sovereign Money Creation” or “Overt Money Finance”, they shared the common trait of using newly created money to fund government spending, rather than relying on commercial banks to create new money through lending.

In a paper that looks at the long-term evolution of central banking around the world, Stefano Ugolini (2011) highlights how the process of financing fiscal deficits with money creation has been surprisingly common:

“According to the modern idea of central banking, those who borrow from the monetary authority are other banks – which, in turn, redistribute credit to the whole economy. In the past, however, such a situation has been the exception rather than the norm. Over the centuries, money-issuing organizations have chiefly supplied credit directly to the state; and even when loans to the banking system have become predominant, central banks have often accorded them provided that the banking system would, in turn, redirect at least part of them towards the government. This disguised obligation has generally taken the form of eligibility criteria for the procurement of credit: in practice, central banks would lend to customers mainly on the security of government bonds, Treasury bills, or the like. With respect to this, the history of the Bank of England is illustrative. During most of its first century of life, the Bank almost exclusively performed direct lending to the government. Only since the 1760s did the sums lent to private customers start to become more substantial; yet, within its portfolio, commercial credit (trade bills) still remained a trifle with respect to government credit. … The presence of government loans and securities on the Bank’s balance sheet continued to be overwhelming throughout the first half of the 19th century; it was only after the reform of 1844 that the Bank entered the commercial credit market more actively. … With the explosion of war finance in the 1910s and the decline of international trade in the 1930s, Treasury bills almost completely ousted trade bills from the discount market … thus making the Bank operate almost exclusively on Treasury securities … Therefore, on the whole, the Bank of England never ceased to play the role of ‘great engine of state’, famously credited to it in 1776 by Adam Smith. …. Another noteworthy example is provided by the Federal Reserve: because of an early rebuttal of the use of the discount window … until the recent crisis the Fed basically restrained all its monetary operations to the Treasury bond market only … All this suggests that throughout the history of central banking, the monetization of sovereign debt has long played a much more important role than it has generally been recognized.”

Ugolini concludes that as the state has often resorted to financing itself through the creation of money, particularly in periods of financial instability. Consequently financing a deficit by creating money “should not necessarily be seen as evil, but rather as an option to be subjected to a benefit-cost assessment – in the light, of course, of the constraints imposed by the institutional arrangements in force.”

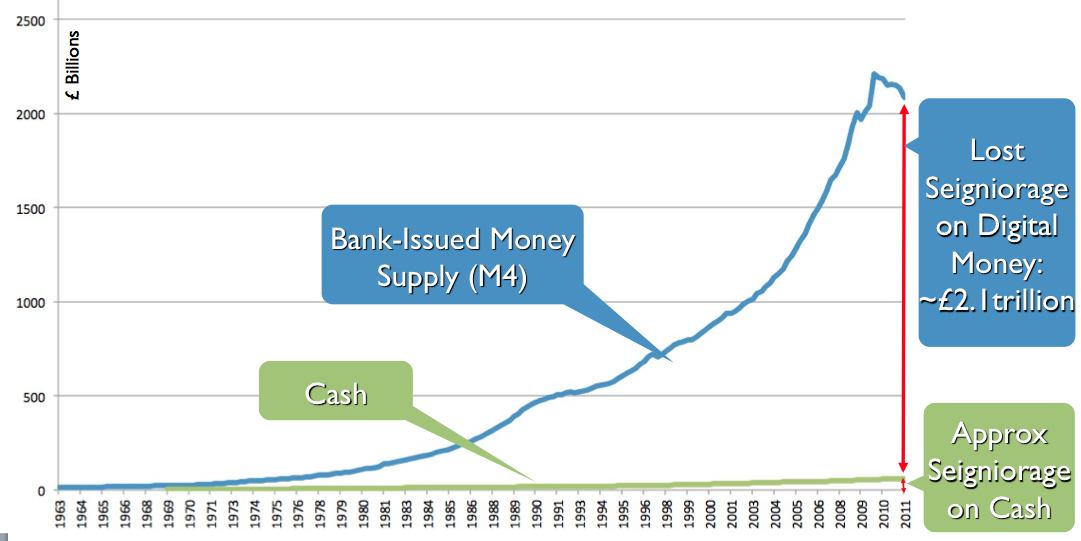

It should also be noted that, today, most countries finance their spending at least in small part through money creation, through the profit they make on the creation of notes and coins (known as seigniorage revenues).

The United Kingdom has a particularly strong history of financing part of its spending with money creation. From the mid-1100s to 1826 the crown partly financed itself through the creation of tally sticks – an early form of currency – which were used to make payments that could later be redeemed against taxes levied.

Likewise, during the First World War, the Treasury issued ‘Bradbury’ notes in order to finance part of its spending.

More recently still, up until the year 2000 the Bank of England regularly used money creation to finance part of the government’s spending, by providing the government with an overdraft facility – ‘the Ways and Means Advance’.

In addition, the recent Funding for Lending scheme, while still relying on commercial banks to create money, involves close cooperation between the government and the Treasury.

These two recent examples are discussed in detail below.

Recent history: The UK Government’s Ways and Means Advance

Until 2000, when EU law forced its cessation, the UK government financed a proportion of its spending through an overdraft facility at the Bank of England known as the Ways and Means account. When used to cover the government’s immediate spending, the liabilities of the Bank of England (i.e. central bank reserves) would increase, creating a form of new money in the process, just as the use of an overdraft at a commercial bank creates money by increasing deposit liabilities. As the Bank of England explains:

“‘Ways and Means’ is the name given to the government’s overdraft facility at the Bank …. Prior to the transfer of the government’s day-to-day sterling cash management from the Bank of England to the Debt Management Office (DMO) in 2000, the outstanding daily balance varied significantly, reflecting net cash flows into and out of government accounts that were not offset by government cash management operations [i.e. borrowing from financial markets]. After the transfer of cash management from the Bank to the DMO, borrowing from the Bank was not used to facilitate day-to-day cash management and the balance was stable at around £13.4 billion until the facility was [mainly] repaid during 2008. … The facility remains available for use…” (Cross et al. 2011) [Our addition in square brackets].

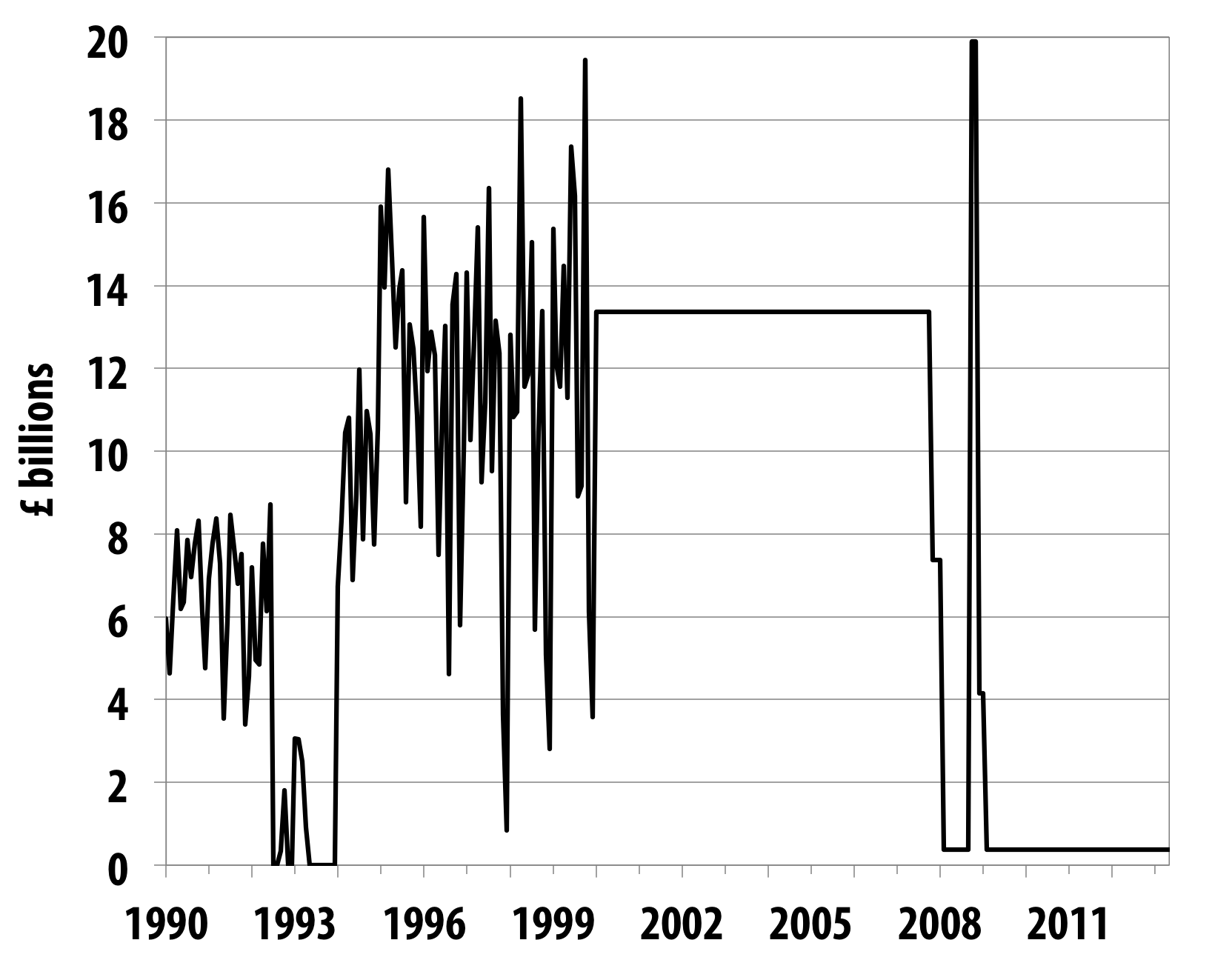

Financing a part of a fiscal deficit with money creation was therefore normal policy up until 2000. Although the advance was only meant to be a temporary solution, with repayments made as either tax receipts came in or bonds were issued (hence the fluctuations in its balance), as figure 18 shows a significant sum remained outstanding at all times.

Ways and Means Advance to HM Government (£ billions)

In 2000 the balance of the Ways and Means Advance was frozen at £13.37 billion. The balance remained outstanding until January 2008, at which time a proportion of it was paid off. Therefore, in effect, from March 2000 to the 24th of January 2008, the central bank and the government had effectively cooperated to finance £13.37 billion of the government’s deficit via money creation. Crucially, when the account was frozen no agreement was made as to when the account would be repaid – it could have remained unpaid indefinitely. If this occurred, £13.37 billion of government spending would have been permanently funded by the creation of money.

Between January and March 2008, the Treasury repaid £13 billion of the £13.37 billion outstanding on the Ways and Means Advance. Since then, the Ways and Means advance has been used to refinance “loans that the Bank had earlier made to the Financial Services Compensation Scheme and to Bradford & Bingley” (Cross et al. 2011). That is, the Bank of England temporarily bailed out Bradford & Bingley with newly created money, contravening European law in the process.

A recent example of Monetary-Fiscal Cooperation Between the Treasury and Bank of England: The Funding for Lending Scheme

The design of Sovereign Money Creation requires the Bank of England and Treasury cooperate, meaning that this requires fiscal-monetary cooperation rather than strict independence between the two functions. A recent interesting example of fiscal-monetary cooperation is the Funding for Lending Scheme. The Funding for Lending Scheme (FLS) allows banks to swap illiquid assets for specially created Treasury Bills with the Bank of England. As a Bank of England paper on the scheme explains:

“The Treasury bills used in the FLS are issued by the Debt Management Office (DMO) specifically for the Scheme. They are liabilities of the National Loan Fund and held by the DMO as retained assets on the Debt Management Account. The Bank borrows the Treasury bills from the DMO under an uncollateralised stock lending agreement.” (Churm et al. 2012) (Emphasis added)

The FLS as currently practised and the proposal for Sovereign Money Creation have two important things in common. First, FLS is an example of the fiscal authority (the Treasury) and the monetary authority (the Bank of England) cooperating with each other in an attempt to increase spending in the economy (by indirectly encouraging the creation of money by commercial banks). Likewise, Sovereign Money Creation proposes fiscal monetary cooperation for the same ends. Second, the Treasury bills used in FLS are issued specifically for the Scheme by the Debt Management Office. These bills are not issued to facilitate government borrowing, but specifically to facilitate this scheme. Likewise, the proposal for Sovereign Money Creation has the Treasury issue securities specifically for Sovereign Money Creation, even though there is no increase in government borrowing.

In Sovereign Money: Paving the Way for a Sustainable Recovery, we’ve outlined the reasons why the government is making a dangerous mistake by relying on further bank lending to boost spending and help the economy grow. We explain how a process called Sovereign Money Creation (SMC), which involves allowing the Bank of England to create money, which would be granted to the government and spent into the real (non-financial) economy would boost spending and employment but without requiring households to borrow even more. Rather than increasing the total amount of debt in the economy, SMC actually lowers it. It would make the current ‘recovery’ into a sustainable one, rather than one fuelled by credit cards and mortgage lending.