Helicopter money: setting the tale straight (A response to the Bank of England’s Underground blog)

In his August 5th post at Bank Underground (“a blog for the Bank of England’s staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies”) Fergus Cumming, a member of the Bank’s Monetary Assessment and Strategy Division, discusses helicopter money proposals. He explains “why such a policy is different to quantitative easing, why it is unlikely to have much impact relative to conventional fiscal measures and the pitfalls associated with pursuing it”.

The term “helicopter money” loosely applies to a policy where the central bank creates new money and then gives it as a non-repayable grant to members of the public. Identical or similar ideas have been recently referred to as QE for the people or ‘People’s QE’, and Positive Money has argued that giving just a fraction of the money created through QE directly to citizens, as a form of “citizens’ bonus”, would have been much more effective than pumping this money into the financial markets.

The fantasy of ‘Ricardian equivalence’

Cumming claims that helicopter money would be ineffective in increasing domestic consumption because people would assume that this ‘hand out’ today would ultimately be paid for by higher taxes in the future. Anticipating these higher taxes, they would choose to save, and not spend, the additional incomes that came from the citizens’ bonus. This is the concept of “Ricardian equivalence”, which argues that if it were the case that people were able to anticipate correctly the future path of government spending and of their families’ welfare, and always based their consumption decisions on maximising their welfare, then they would only spend any additional handout from government if they were convinced that the increase in government spending would not result in additional taxes in the future. Unless they believed this, they would save and not spend the additional income arising from the increased government spending, in order to pay those additional taxes, once they were levied, without impacting on their future disposable incomes.

From this thought experiment it is concluded that if the government increases spending by increasing borrowing, which will increase future debt service costs, then the effect will be indistinguishable from (equivalent to) the increased spending being financed by increased taxes. In the former case there would be no increase in consumption because the recipients of the increased government spending would save their extra income so that they (or their children, to whom they would bequeath their savings) would be able to afford the increased future taxes. In the latter case there would be no increase in consumption because the increase in incomes from government spending would be cancelled out by the reduction in disposable incomes due to the increased taxes in the future.

The author argues that Ricardian equivalence would apply in his scenario, where helicopter money is financed by selling new government debt to the finance sector, with the central bank creating additional reserves to buy back government debt from the finance sector and thereby restore their bank balances. This conclusion flies in the face of evidence of empirical studies (e.g. here, here and here) showing that people do not correctly anticipate the future path of government spending and of their own and their families’ welfare. Even in controlled experiments where they were provided with equivalent information, they do not make decisions which correctly maximise their or their children’s welfare. Since the only circumstances in which Ricardian equivalence might occur do not exist anywhere in reality, there are no grounds for claiming that helicopter money will fail to lead to increased consumer spending, even if the process is initially financed by increased government debt.

The author’s scenario is one he invented for the purpose of invoking Ricardian equivalence. The actual proposals for helicopter money as put forward initially by Milton Friedman, and in the Sovereign Money proposals of Positive Money, involve the deposit by the government of a zero-coupon perpetual bond at the central bank in exchange for the reserves needed to finance additional government spending or distributions to households. Being zero coupon, the bond would pay no interest and therefore would not add to the government’s debt servicing burden. Being perpetual, the bond would never be repaid and would therefore require no future taxation or debt renewal. He mentions this difference without further comment, but he raised a second objection to helicopter money concerning the central bank’s balance sheet, which does have implications for the actual proposals.

The impact on interest costs for the Bank of England

Currently, the Bank of England pays interest to banks on the reserves they hold in excess of those required for payments settlement purposes. This policy began in 2006 and initially applied only if banks managed their reserve accounts balances to meet certain conditions. Three years later, quantitative easing meant that banks lost control of their balances (since the QE process meant that reserves were forced on them by the central bank). However, since 2009 interest has been paid on all reserves regardless. Currently, this interest is paid out of the income arising from the government bonds that the Bank purchased during QE (i.e. the government pays interest to the Bank of England on the bonds that it holds, then the Bank of England passes some of this interest on to holders of reserves).

Helicopter money would create additional central bank reserves, but unless the Bank acquired additional interest-paying assets in the process, to pay interest on these additional reserves would involve the continual creation of yet more reserves. This is because with interest-paying assets (e.g. government bonds), the payment of interest to banks would effectively involve merely a transfer of reserves from the account of the bond issuer (the government) or the bond issuer’s bank (for corporate bonds) to the reserve account held by the banks receiving the interest. With no additional interest income, however, interest payment would be from the Bank’s capital to bank reserves, creating new reserves with no offsetting reduction in liabilities, reducing the Bank of England’s equity, and ultimately threatening the Bank’s solvency.

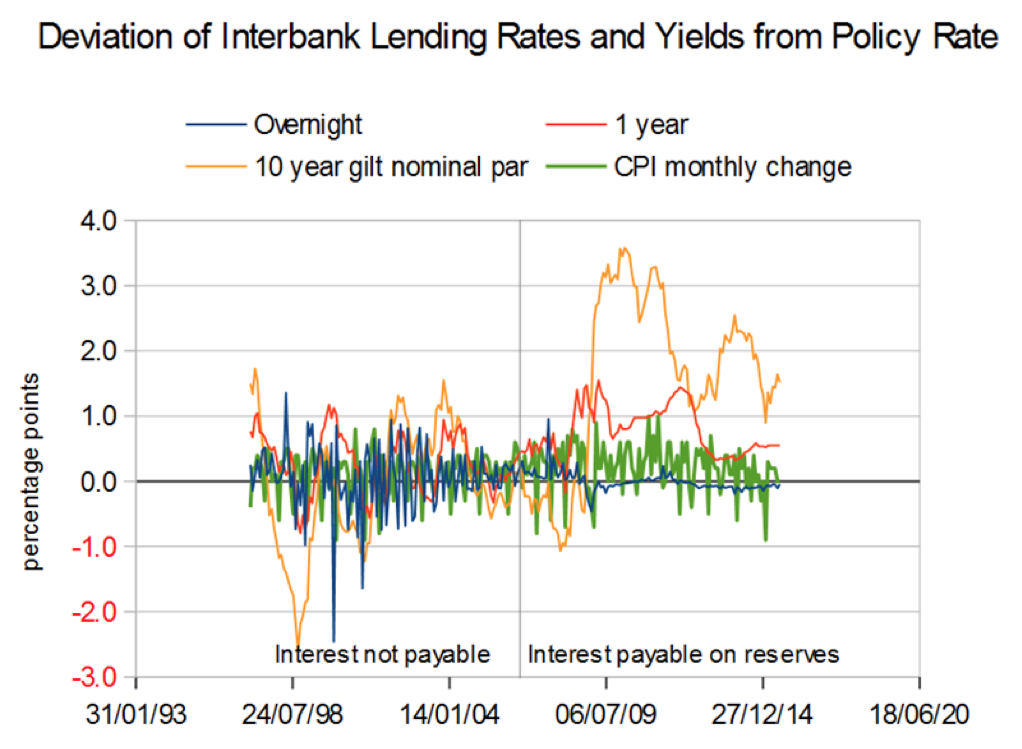

The only way to avoid this would be for the Bank to stop paying interest on reserves. But, according to the author, this would mean that the Bank would lose control over interest rates and therefore over inflation. The logic of this argument requires that the payment of interest on reserves enables the Bank to control interest rates, and that in turn provides control over inflation. The policy of paying interest on reserves was indeed introduced in order to allow the Bank to control overnight interest rates, with the expectation that longer term interest rates would then become anchored by the market by the level of overnight rates. Mainstream economic theory then supposed that changes in interest rates would feed through to changes in economic activity, incomes and prices. The empirical data show that following the introduction of interest payments, the Bank was indeed successful in anchoring overnight interest rates to its own policy rate, and longer term rates were greatly stabilised. However, the levels of longer term rates were unrelated to the level of the policy rate. There has been no discernable impact on price stability as measured by monthly changes in CPI.

The chart below compares changes in overnight and 12-month sterling LIBOR, and yields on 10 year gilts, relative to the official Bank Rate (represented by the 0.0 point on the vertical axis) over the periods before and after interest became payable on banks’ reserves. Fluctuations in all three rates were considerably less frequent after the introduction of interest payments and, except for a single peak in 2007 following Northern Rock, the overnight rate remains locked to the policy rate. The longer term rates however remain subject to wide, though less wild, swings away from the policy rate. The month on month change in the level of the Consumer Price Index is shown in green and shows no reduction in volatility since the introduction of interest payment, compared with before. The chart therefore provides no evidence that the Bank’s closer control over the level of overnight rates, and over at least the volatility of longer-term rates, has any impact on inflation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there need be no concerns that helicopter money will fail to stimulate consumer spending. The argument that this would be the case is based on a thought experiment built on unrealisable assumptions that never apply in reality. Neither should it be rejected on the grounds of fears that the Bank would “lose control” over inflation, since there is no evidence that it currently has any control, or that what control it may have is dependent on paying interest on reserve accounts.

Helicopter money would, however, involve a trade-off between debt servicing costs and interest rate volatility, and the level of profit generated by the central bank (and transferred to the government). It is probably a valid assumption that volatile interest rates are economically undesirable, and the evidence points to the effective role played by the payment of interest on bank reserves in reducing interest rate volatility, so it would probably be undesirable to stop paying interest just in order to implement helicopter money.

The implementation process would therefore involve either a higher government debt burden to finance the paying of interest on the additional reserves, or a reduction in the Treasury’s dividend from the central bank’s operating surplus. The Treasury’s dividend is of the order of £60 million per year, so at a Bank rate of 0.5% that would be sufficient to finance interest payments on an additional £12 billion of reserves in helicopter money backed by zero-coupon perpetual bonds. Conversely, with a programme initiated by the sale of new conventional gilts and with an equivalent amount of existing 10-year bonds bought back by the Bank yielding around 1.5 percentage points above Bank rate (four times a Bank rate of 0.5%), a £12 billion programme of helicopter money would require a market issue of £3 billion in new bonds and a balancing issue of £9 billion in zero-coupon perpetuals. Larger programmes could be financed pro-rata at the same level of Bank rate, but would cost more in terms of interest-yielding bonds at higher levels since the spread of gilt yield over Bank rate would not increase pro-rata.

However, even if some interest must be paid on reserves created by helicopter money, this cost is likely to be far outweighed by the additional tax revenue generated from the spending that helicopter money finances.