A man’s world: Why gender parity on the ECB matters

The Eurogroup is about to miss the opportunity to make the ECB’s Board gender-equal for the first time in history.

There are still too few women in leadership positions, especially in economics and finance – including central banking. The euro area and the European Central Bank is no exception to the rule.

The recent appointments of Christine Lagarde as ECB President and Isabel Schnabel to the Board in 2019 brought the count of women on the board to an all-time high of two.

With the departure of Yves Mersch from the ECB’s Executive Board at the end of the year, an opportunity arose to bring about a perfectly gender-balanced board for the first time. However, this opportunity is about to be wasted, as two men (Frank Elderson and Bostjan Jazbek) are currently being proposed to become the next ECB board member.

The ECB’s Executive Board consists of the President, Vice President and four other board members elected for an eight-year, non-renewable term. The Board is responsible for the implementation of monetary policy, and sets the policy agenda for the Governing Council, which includes the governors of the 19 national central banks.

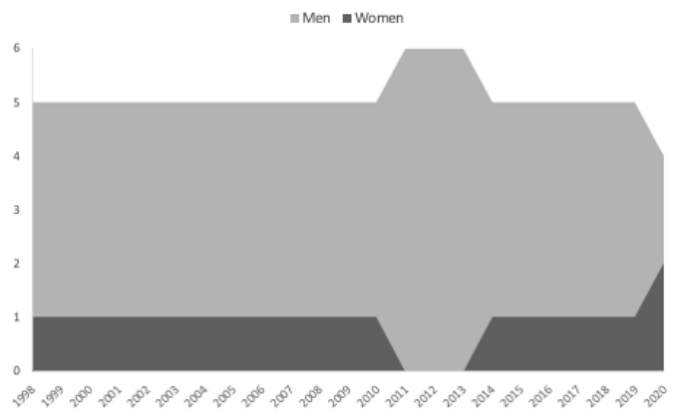

The ECB Executive Board is arguably the most powerful entity at the ECB. Apart from Christine Lagarde and Isabel Schnabel, only three women have served on the Board since its establishment in 1998. Until now, there has never been more than one female on the Executive Board.

Figure 1: Gender balance on the ECB Executive Board

Source: ECB website.

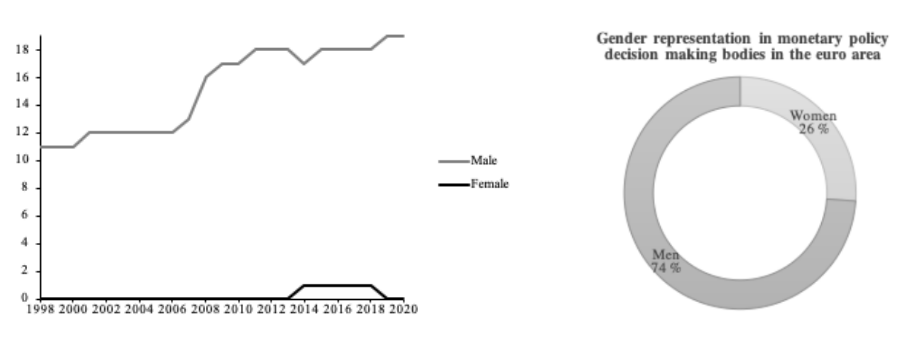

The selection of a woman would place the ECB at the forefront of progress and equality in the world of central banks, which remain a man’s world. The upcoming appointment to the six-seat Board is the last slot available until 2026, and the last of a round of vacancies that included Christine Lagarde’s appointment as the ECB’s first female president. Lagarde has made her ambition of improving the gender balance at the ECB known. She recently commented on the gender balance of the governing council, noting that “the 19 central banks in the euro area are exclusively run by men”.

In fact, there has only been one female governor in the lifetime of the Governing Council, Chrystalla Georghadji who was governor of the Cyprus National Bank from 2014 to 2018.

Furthermore, women remain underrepresented on national central bank boards, which are significant monetary policy decision-making bodies in the euro area.

Figure 2: Gender balance on the Governing Council (left), and the national central banks (right)

Source: Central banks’ websites (including Banco de España, Banque de France, Latvijas Banka, De Nederlandsche Bank, Eesti Pank, Central Bank of Ireland, European Central Bank, Bundesbank, Suomen Pankki, Central Bank of Malta, Banco de Portugal, Bank of Slovenia, Banque Central de Luxembourg, Baca d’Italia, Bank of Lithuania, Swiss National Bank, National Bank of Greece, Central Bank of Cyprus, Bank of England, Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Národna Banka Slovenska, National Bank of Belgium.)

Why gender parity matters

As central banks increasingly operate in the public eye, balanced leadership is more important than ever. Yet women remain underrepresented in central banks at all levels, and particularly in senior positions. In fact, from 173 central banks worldwide, only 14 are headed by women.

As Isabel Schnabel said in a speech on the 28th of September: The gender imbalance in economics is a long-standing and persistent phenomenon. There are systemic barriers to women’s career progression, research has shown that female-authored papers take longer to peer-review, and the ones that are published receive more citations suggesting that “female authors are held to higher standards during the review process”.

Women have been found to hold statistically different views on economic questions, which have important implications for policymaking and real economic outcomes. On average the study published by the IMF found women to be less confident in market solutions, and more positive to government intervention, government spending, taxation, and redistribution. The same study found that women are more conscious of both diversity and equality of opportunity than their male counterparts.

Hence, the increased female representation might increase diversity more generally. Or in the words of Sharon Donnery, deputy governor of the Bank of Ireland, “we need to make sure the rising tide lifts all boats.” As we make progress on gender equality, we must remember to push for diversity and promotion of underrepresented groups more broadly.

Why should we care in the midst of the pandemic?

A failure to represent society might undermine the independence of central banks altogether, as Erik Jones argues in a recent blog post. In times of crisis like the one we have today, Central Bank stimulus and money printing are necessary to keep the economy afloat.

Many central banks are experimenting with “unconventional” instruments and monetary policies. Arguments for the experts’ independence become weaker with each step of innovation. The crisis puts more power in the hands of monetary policy. Our fate is in their hands, but we have no way of influencing their choices as central bankers are not democratically elected, and thus not accountable in the same way as politicians.

Going forward, one way to resolve this issue of accountability might be to focus on central bankers themselves. Ensuring that decision making bodies represent the people increases the chance that they connect with the people and gain the trust they need to justify their independence.

Female representation is important because diversity matters for the functioning of any board or team. In demanding times like this, we need to think outside the box. The financial crisis serves as a recent memory of how bad the result can be when a group of like-minded people fails to see what is really going on.