European Central Bank reveals it made huge profits from the Eurozone crisis

The European Central Bank just revealed it made 61 billion euros of profits out of its intervention in crisis hit countries such as Greece, Italy, Spain, Ireland and Portugal.

Since last year, Positive Money Europe has been very active in raising awareness of the fact that the European Central Bank made huge profits on the back of the Greek crisis. According to our research, based on fragmented information disseminated across various report from the ECB, the IMF and other public agencies, we estimated the ECB had made 18 billions euros of profits.

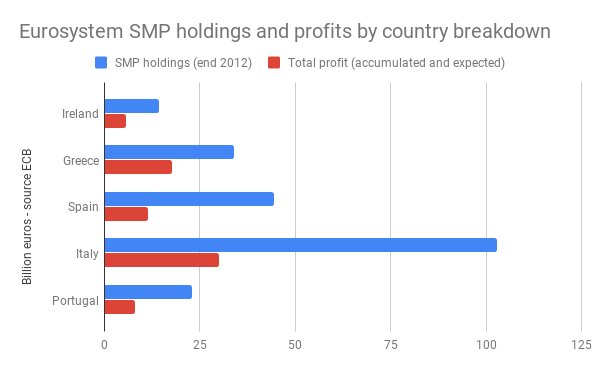

New data revealed by the ECB few weeks ago not only confirm our claim, but it reveals that the ECB didn’t just make money out of Greece, but also Spain, Portugal, Italy and Ireland, to the tune of 73 billions overall.

The profits come out of the so called “Securities Market Programme” (SMP), which was triggered in May 2010 when markets were panicking over the sustainability of Greece’s debt and the likely contagion effect on other Southern countries. To contain the crisis, the ECB purchased at least 218 billion euros of bonds from distressed countries.

Although this was not its intended purpose, the SMP programme ended up being a huge cash-machine for the Eurosystem. According to data revealed early April, the ECB has already accumulated 61 billion of profits from SMP since 2010 until now, with 12 billions more expected by the time the programme completely expires. In addition, some central banks made additional profits through their so called “ANFA” operations – which are related to central banks own investments. Unfortunately, the ECB does not have the power to disclose ANFA data from national central banks.

The disclosure of the data by the ECB comes after the pressure from Positive Money Europe and the European Parliament. Thanks to an amendment suggested by Positive Money Europe and tabled by Belgian MEP Philippe Lamberts and Irish MEP Matt Carthy, a call for more transparency on SMP profits was included included in the Parliament’s annual resolution on the European Central Bank which was adopted last January.

We welcome that the European Central Bank agreed to provide the data in its “feedback” to the European Parliament. Nevertheless It is disappointing that the Eurogroup, which took the decision of the refunds in the first place, was not able to fulfill the same transparency request. Despite our cordial exchange with the Eurogroup President, his office was not able to provide any useful information other than the one provided by the ECB.

🇪🇺👍This is central bank accountability in practice: the #ECB disclosed the detailed profits from SMP for all countries🇬🇷🇵🇹🇮🇪🇪🇸🇮🇹. This was a demand we submitted to the European Parliament in September. 🙏Thank you MEPs @ph_lamberts and @MattCarthy for tabling the amendment! pic.twitter.com/FKb1xPneRq

— Positive Money Europe (@PositiveMoneyEU) April 12, 2019

Vulture funds should be jealous of the ECB

A simple calculation shows the SMP portfolio earned the ECB a mighty 33% return – a return ration which many investment funds would be jealous of. Of course, the reason the return is so high is because the ECB triggered those massive purchases at the time when most market players were selling those bonds, by fear of a debt restructuring – very much like a vulture fund would typically do. Looking more closely at the country breakdown, we see that the yield on greek bonds was particularly high (52%) while returns on Spanish and Italian bonds were more modest but still very high (around 25%).

To be fair, the ECB did not exactly keep 73 billions of profits just for itself out of the operation. Just like any income generated by the ECB’s monetary policy, the SMP profits are only partly retained by the ECB to build up its reserves, while the rest (as the ECB explains here) is distributed to all national central banks according to their share of the ECB’s capital. In turn, national central banks distribute some of their profits to their national governments.

This distribution rule probably explains partly why 10bn euros are missing from the amount of refunds promised to Greece by the Eurogroup. We estimate that the ECB retained around 2.5bn, while the rest probably ended up in the pockets of national central banks and governments.

Given this background, it is not only questionable why the Eurogroup did not agree to refund all the profit, but it is even more shameful that some countries used their power to block or suspend the refunds as a means of blackmail to obtain further structural reforms from the Greek authorities.