Deflation, Wages, and Productivity: Connecting the Dots

For the first time in half a century, the UK has officially entered deflation. But wait; is that a good thing or a bad thing? Why is there all of a sudden so much talk about wages and productivity? And exactly what is deflation again?

Deflation in the UK Explained

Consumer prices have dropped by 0.1% over the course of the last 12 months. An annual drop in consumer prices is what economists refer to as ‘deflation’. According to figures given by the ONS, the last time consumer prices fell was in 1960.

Many potential first-time house buyers and those worried about the current housing crisis may have rejoiced when first hearing the news. However, it is important to note that this particular indicator (CPI index) only measures the price of consumer goods (loosely defined as the final products that shops sell i.e. food, clothing, and cars) and so house prices are not included. Recent figures suggest that house prices have actually increased by roughly 9.4% in England and 14.6% in Scotland.

But isn’t a drop in the price of consumer goods generally a positive thing? The answer isn’t simple, but it basically comes down to how long such a drop would go on for. A short bout of deflation will give consumers some extra disposable income at the end of the month, as incomes will be higher relative to prices. In the short-term, this equates to increased spending power and should help stimulate the economy.

On the other hand, over the long run, falling prices eventually means that business profits are diminishing, and what follows is lower incomes. Lower incomes means less spending and a consequent further drop in prices and business profits. This process can easily reinforce itself, leading to what Irving Fisher referred to in commenting on the Great Depression, a ‘deflationary spiral’. A deflationary spiral can be particularly harmful for a nation with high levels of private sector debt, as incomes fall but level of debts remain the same − increasing the burden of servicing such debts.

In this case, however, deflation is apparently due primarily to falling oil prices and commodity prices. Which implies that it will be short-term, and should be a stimulant to the economy, as George Osborne notes:

“As the Governor of the Bank of England said only last week, we should not mistake this for damaging deflation. Instead we should welcome the positive effects that lower food and energy prices bring for households…”

There are still some concerns, as General Secretary of the TUC Frances O’Grady states:

“The first period of negative inflation in over half a century could turn out to be the canary in the mine, signalling that there’s something very wrong with the recovery.”

The worry stems from the fact that while the majority of deflation is due to exogenous factors (oil and commodity prices), some if it is also due to the current state of the economy. Indeed, core inflation (consumer prices stripped of oil and commodity prices) is about half of its usual trend, which means some domestic factors are also responsible for current deflation. The question is what are these domestic factors?

The Composition of Inflation: All eyes on ‘Core Inflation’

Wages and Inflation

The Bank of England recently explained, “…the more enduring influences on UK inflation will be the evolution of domestic costs, particularly wages relative to productivity… these influences are currently weighing on core inflation”. Wages play a large part in determining household ‘spending power’, and if wages are not increasing relative to prices then household spending power and general standards of living are effectively diminishing.

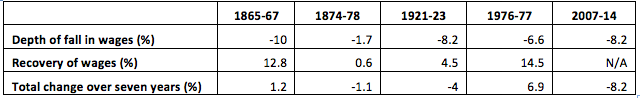

With recent low levels of inflation and now deflation, real earnings are finally beginning to increase (albeit only marginally). However, before 2015, the UK was suffering from the longest and most severe decline in real earnings since records began in the Victorian times.

Historic Comparison of Fall in Real Wages

The Bank of England shows that growth in wages remain well below pre-crisis levels. According to the Bank, this is because “employment growth since mid-2013 has been disproportionately in lower-skilled jobs…”.

What about Productivity? Why is Everyone Talking About it?

According to the Bank of England, the above implies that the UK’s economic recovery has been underpinned by an increase labour force (primarily in low skilled jobs). Real wages have only increased due to exceptionally low levels of inflation. For there to be a sustained increase in wages (living standards) there has to be an increase in productivity. The Bank’s logic is quite simple, for businesses to be able to pay workers more per hour, businesses have to produce more output per hour. The problem however, is that productivity has been depressingly stagnant for some time now.

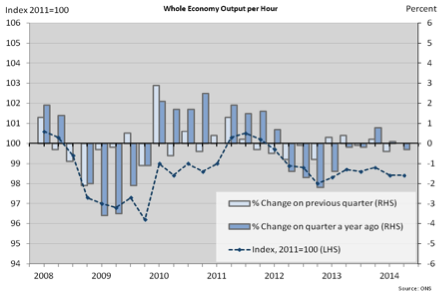

ONS figures reveal that compared to the previous quarter, Q4 productivity per hour fell by 0.2%. Indeed, labour productivity in 2014 was exactly the same as it was in 2013, still below levels experienced in 2007. It is now estimated that productivity levels are roughly 16% below historic trends. The UK is now roughly a fifth less productive than the average G7 country, and produces 40% less per worker than the USA.

Productivity in the UK

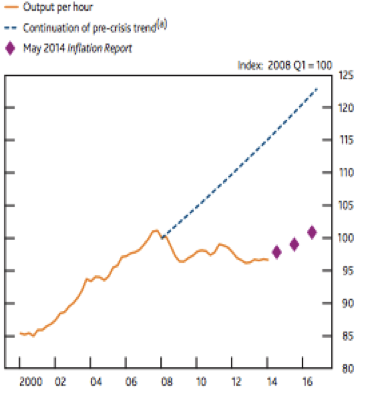

Current Productivity vs. Pre-Crisis Trend

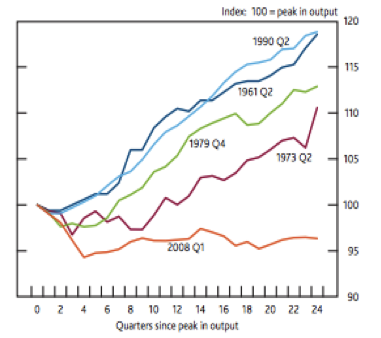

Productivity After Crises

The growth in low skills jobs has helped prompt the last two years of economic growth, yet this expansion of the labour market is not sustainable over the long run. Thus, both growth and real wages are dependent on a pick up in productivity, as Martin Wolf recently suggested:

“In the short run, stagnant productivity allowed the economy to combine weak expansion of overall output with decent jobs performance. In the long run, however, productivity determines standards of living. If the former stagnates, so will the latter.”

What does Future Productivity Look Like?

The Bank of England has somewhat of an opaque stance on how productivity growth will look in the future, suggesting:

“Productivity is projected to grow only modestly in the year ahead, before returning towards, but remaining below, past average growth rates.”

The Bank then suggests:

“That recovery (in productivity) reflects a combination of factors. They include the lessening of compositional effects, a pick-up in the reallocation of resources to new and more dynamic firms, and the effects of the investment recovery coming through.”

The truth is that the Bank isn’t very sure about its own projection on productivity, as it later states: “There remain considerable uncertainties around the timing and extent of that pickup.”

The conclusions of a recent report by the Bank titled, ‘The UK Productivity Puzzle’ also makes this general stance clear, conceding that “…there remains considerable uncertainty around the timing and extent of any strengthening.”

Indeed, Mark Carney governor of the Bank of England stated:

“Among the many uncertainties we face, the timing and extent of any prospective pick-up in productivity growth remains our most difficult judgment.”

In essence, there is no telling what might happen to productivity over the short and medium term.

Sovereign Money the Solution?

While we do not aim to predict what will happen with productivity we do offer proposals to stimulate it. Martin Wolf recently suggested that the necessary ingredient for the recipe that leads to a rise in living standards and improved productivity growth is “buoyant demand”.

Indeed, perhaps what is missing in the Bank of England’s analysis is a discussion on demand. For example, productivity in the UK may also be stagnant or falling because demand is stagnant or falling and there is no call for increased production.

An increase aggregate demand effectively translates into increased private sector spending. Considering that the velocity of spending is expected to stay relatively stable, increased private sector spending will depend on households taking on more debt or using their savings. Thus, it is no surprise that savings are projected to continue to decrease while the total household debt to income ratio will soon surpass its pre-crisis high, and increase to 184% by 2020. In essence, under the current monetary system, in order to increase demand and potentially boost productivity, households will have to dip into their savings or take on more debt.

UK Household Debt-to-Income and Savings

Another option is for the Bank of England to create money free of debt and inject it directly into the real economy (see our Sovereign Money proposals). Such spending can be for infrastructure projects, or as authors for the Guardian recently suggested for a citizens dividend fund. This increase in spending/demand will prompt businesses to produce more, and would eventually lead to a higher level of output per hour, allowing the business to eventually increase incomes.

How productivity and living standards will increase is very much up in the air, but if it does increase, under the current system it will be largely due to increased levels of private debt. Sovereign Money present a viable alternative, that will stimulate productivity and raise living standards without relying on more debt.