Defl-Asian: The biggest threat to Asian economies & global financial stability?

Prices are dropping quickly across the board in Asia, productivity is declining, private debt is soaring, growth is slowing, and the prospect of deflation is looming across the entire region. Indeed, deflation is possibly the biggest threat to Asian economies, not to mention global financial stability.

The traditional tools for preventing such deflation have all but been exhausted, as the region is already at risk of an all-out currency war and the private sector is considerably over-leveraged. Its time for policy-makers to start thinking outside of the box, and consider how debt free money creation for the real economy could stimulate aggregate demand and thwart off deflation in Asia.

Deflation in Asia

Prices all over Asia are showing signs of decline, indeed deflation is not just knocking but banging on the doors throughout the continent. Already in November 2014, Ambrose Evans Pritchard described China, as being ‘one shock away from deflation’. It has since lowered its interest rates and reserve ratio twice, which had no effect on the tumbling prices in the real economy.

Japan, Asia’s second largest economy has been experiencing bouts of deflation for the last 20 years. In fact, Japan has kept its benchmark interest rate in zero-bound territory for the last two decades and is now engaged in the biggest QE project in the world, yet prices are still in deflation territory.

Asia’s third largest economy, India, recently experienced its largest decline in wholesale prices – which fell by 2.33% – its fifth month of decline in a row. On the other hand, industrial annual production dropped to 2.1% in March, roughly half of that of February.

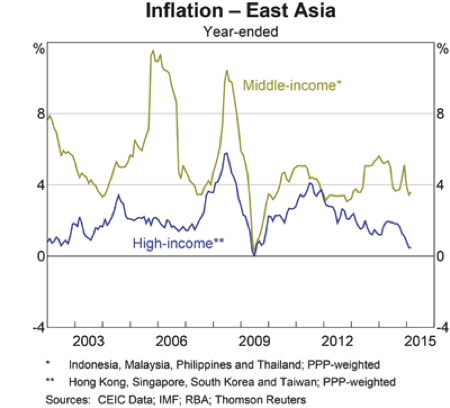

This trend seems to be common to all Asia’s high-income economies, with inflation rates generally falling, and even in middle-income countries, inflation appears to be falling below trend.

Why is Deflation Such a Problem?

Central banks across the globe have attributed low levels of inflation and the prospect of deflation on lower oil prices. However, as Philip Neumann points out in the FT article, “The trouble is there are no signs that growth is benefiting from lower oil prices. By now, demand should have started to strengthen.”.

The Bank of International Settlements recently reported that deflation has hardly ever been representative of a frail economy. However, this is because traditionally deflation is generally associated with aggregate deleveraging after a crisis – where debts are paid down faster than new debts are incurred.

Since 2009 however, debt levels for the entire region (excluding Japan) have increased from 147% to 207% of regional GDP. Asia is accordingly not deleveraging in the face of this deflation, which makes the prospect of deflation all the more alarming. If an asset bubble eventually busts during a deflationary phase the detrimental effects for the economy and stability will be immense. Rising debt requires rising incomes to service it, but deflation tends to lead to lower incomes as economic activity falls, increasing the burden of debt servicing. If asset prices start falling also, incomes cannot be supplemented by asset sales to alleviate that burden.

Furthermore, since the financial crisis the majority of Asian central banks have cut their interest rates and injected extra liquidity into the financial markets in an attempt to reduce the value of their currencies relative to commodities – to the extent that some have suggested that the region has been immersed in an all out currency war. Not only are these macro-economic tools largely exhausted, but the already high levels of debt makes reliance upon them all the more dangerous.

What are the Options?

With limited options at Asia’s disposal, the FT’s Philip Neumann asks, “What, then, is to be done?”. Considering the high level of private sector debt in Asia, Neumann argues that further monetary easing will have little effect, and thus suggests fiscal easing would be more prudent. At Positive Money, we would ask why not combine the two and create debt-free Sovereign Money for fiscal stimulus.

Instead of relying on more borrowing to stimulate aggregate demand and reverse deflation, Sovereign Money could be injected directly into the economy for productive purposes. Just as with QE, this would serve to devalue the currency, which would make exports cheaper relative to other countries’ goods, but instead of waiting for the benefits to trickle down from the financial markets, as with QE, the real economy would be stimulated directly by the injections of Sovereign Money. Not only would consumption pick-up and prices eventually recover, but such improvement in economic performance would not be dependent on increased debt levels.

With a limited number of macro-economic tools available, it is time policy makers start think outside of the box and seriously consider Sovereign Money.