Big issues are at stake in this election but public debt isn’t one of them

With the major parties outlining their spending plans, some politicians and commentators have expressed concern about the level of public debt. But – as has happened in previous campaigns – this focus risks private debt being ignored, the financial sector getting let off the hook, and the most important social and environmental challenges becoming secondary issues behind ‘the responsible management of public finances’. We can’t let that happen this time round.

As ever, a premise of much economic commentary during election time is the idea that we must run a balanced budget (or possibly even a budget surplus), to avoid ‘burdening’ future generations with a larger national debt. On the right of the political spectrum, the predominant argument is usually that this can only be accomplished with relatively low spending, though even the Tories have now relaxed their fiscal rules. On the left, the focus is on higher taxation for the wealthy and more spending to stimulate economic activity, which results in higher government revenue. The practical difference between these two positions is far from trivial, but both tend to view budget deficits in the short run and public debt in the long run as fundamentally bad things.

A fear of public deficits and debt is rooted in the assumption that government finances are the same as those of a household. Any spending that a household undertakes must be covered by income. It is important to note that the dominant view among more left-leaning politicians and commentators does begin to move away from this analogy, as it acknowledges that for a government, lower spending dampens economic activity and results in lower revenue, and if the economy is not producing at full capacity, higher spending will lead to higher revenue. This provides valuable insight, but higher spending now is still usually justified by the increased tax-take in the future (in addition to higher taxes in the present), meaning that there remains a belief that spending should ultimately be covered by revenue.

In election coverage over the past couple weeks, the household analogy has been front and centre. The question of ‘how are you going to pay for it?’ is being thrown fervently at any investment proposals coming from either side of the political spectrum. Sajid Javid has claimed that the previous Labour government’s fiscal policies caused the financial crisis of 2007-08, and that the current Labour proposals would ‘cause an economic crisis within months’. The response to the latter has been that the Conservatives’ numbers are wrong, implicitly (if not explicitly) accepting that balancing the budget is a worthy goal. Even physicist Brian Cox has chimed in, proclaiming on Twitter that both major parties’ spending programs will not be feasible “if international investors take fright” following Moody’s downgrading of UK government bonds.

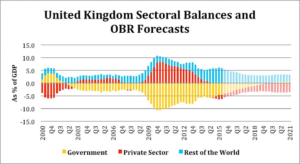

Fixation on ‘responsible’ budgeting and the national debt seems to be a recurrent feature of election campaigns, with frequent warnings that profligate spending risks plunging the UK into a crisis. But if previous economic crises (Eurozone aside) are any guide, public debt is rarely the culprit. Neither the Great Depression nor the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-08 were preceded by expansions in the ratio of public debt to GDP, and basic accounting helps explain why. Leaving aside cross-border flows of money in and out of the UK, if the government runs a deficit, the private sector must be in surplus by the exact same amount. In other words, if the government net spends (i.e. it spends more on the public than it taxes them) this increases private sector savings, and if the government net saves (i.e. spends less on the public than it taxes them), this decreases private sector savings.

Therefore, calling for public surpluses is equivalent to calling for the extraction of money from the private sector. Throughout austerity, this extraction has fallen most heavily on the least powerful in the private sector, namely poor households, which have ended up saddled in unpayable private debt (which is the kind of debt that really matters, as elaborated further below). The UK’s trade deficit is a further drain on domestic private sector savings, as there is more money flowing out of the country for the purchase of imports than there is money coming in from exports. The diagram below illustrates the public, private, and foreign sector balances for the UK:

Source: Graeber 2015

This sheds a completely different light on the conventional wisdom economic doctrine that balancing the budget is ‘fiscally responsible’. What George Osborne failed to tell you when celebrating his balancing of the budget was that this ‘achievement’ meant that the private sector was now running a deficit equal to the foreign sector’s surplus (i.e. the trade deficit). Unless you’re a particularly wealthy individual, a profitable corporation, or a bank, this is bad news for your efforts to balance your own books.

This is not to say that there are no functional or institutional constraints on the size and nature of public debt, but rather that our fixation on balancing the government’s books is misplaced. Ultimately, we need a far more qualitative approach to fiscal policy fit for the societal and environmental challenges that we face. Debate must be centered on the extent to which spending and taxation programmes address the climate and ecological crises and allow humans to live happy, dignified and fulfilling lives. Whether this results ultimately in a budget deficit or a budget surplus is much less important than is often assumed.

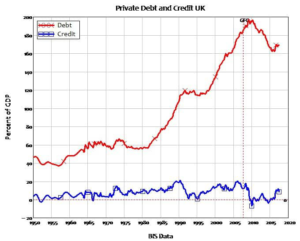

As mentioned above, however, there is a type of debt that tends to matter far more: private debt, which is the main source of financial instability. An unprecedented growth of private debt in the UK (and many other countries, including the US) was at the root of the GFC. The expansion spanned from the early 1980s, when the ratio of private debt to GDP was around 60%, all the way up to about 190% when the crisis hit.

Source: Keen 2017

As Richard Vague shows in his recent book, all financial crises around the world in the last 150 years were actually preceded by significant expansions of the private debt to GDP ratio. When income levels don’t grow fast enough to keep up with the debt burden, defaults become inevitable.

Therefore, in order to address financial instability, we must look first to the creators and masters of private debt: commercial banks. As Positive Money and Post Keynesian economists have emphasised for years, when commercial banks make a loan, they simultaneously create a matching deposit, effectively creating money through a few keystrokes on a computer. And yet despite our research and campaigning on this issue and the Bank of England releasing a report in 2014 confirming that this is how money is created, one of our polls showed 85% of MPs still don’t understand this key element of our economic system.

Commercial bank money creation becomes most problematic in economic booms, as insufficiently regulated banks relax their standards and create too much money for sectors of the economy that have no societally beneficial use for it. The vast majority of new loans are lent into speculative markets such as real estate and the financial sector (as shown in the figure below), which serves only to inflate asset bubbles:

Source: Positive Money, based on Bank of England data.

Eventually, incomes can’t keep up with debt repayments, defaults rise, bank lending dries up, asset prices tank and the whole system crashes. But despite this process being driven by the financial system, it’s public debt that ends up taking the blame in much of the political discourse.

In order to have constructive conversations about economic stability and prosperity in this election, we need to look well beyond the national debt. We need to expand public understanding of our monetary and financial systems and crucially, their interactions with the climate and ecological crises. Fiscal policy has an important role to play, but we must also talk about monetary and financial reforms that will break the power of the banks and help enable an economic system that serves people and planet, rather than the other way around.

Many thanks to Zack Livingstone for valuable discussion and comments on this post.