Bank robbery as part of a system

‘Bank Robbery’ is not a book about how to rob a bank, it’s about how banks rob us; not primarily for their own benefit, but as part of a system that we must fix if we are to have a just and safer world. How money is created has, for several centuries, been the source not just of inequality, but also of unaccountability in government and of huge power for created capital to exploit the world and its peoples. It can be argued whether the system has served us well or badly in the past; it is certain, however, that it must be reformed today.

The title ‘Bank Robbery’ sounds a bit sensationalist: perhaps people think it’s not meant to be taken too seriously. Banking is not robbery, surely: banks provide a service – even if they do charge too much, and behave badly when they think they can get away with it. But actually, the title is to be taken literally. Robbery means ‘theft backed up by violence or by threat of violence’. The theft is that banks create money out of nothing for the use of themselves and selected others: the overall effect of this is a continual transfer of assets from the rest of us to governments and a financial elite. The violence, or threat of violence, is what the state may use to back up the rule of law: in this case, to enforce the laws that allow banks to create money.

It’s obvious to most people that if there is to be a functioning rule of law, the State must be able to use force when necessary to back it up. So it’s our responsibility, as citizens and voters, to make sure that the laws are just. In the West, we tend to assume that if an unjust law does exist it will soon be changed, because public opinion will not put up with it.

There have been many unjust laws in our history: the Corn Laws, laws supporting the slave trade, laws about who is entitled to vote, laws about the property rights of married women are a few examples. Many of these unjust laws lasted for generations before they were changed or repealed.

There are strong reasons why so few people talk about changing the laws that allow banks to create money. First, the public is ignorant about how money is created, and about the laws which support banking. Second, powerful vested interests depend upon the banks, and are happy to keep things the way they are. Third, most people are nervous of change, especially if it might upset how they make a living.

1. Public Ignorance

First, take public ignorance. Most people don’t understand how banks create money. In fact, it is very simple:

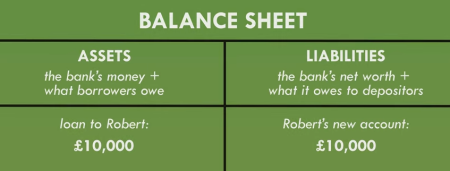

When a bank lends, it creates two equal-and-opposite debts (promises to pay money): one from the bank to the borrower, one from the borrower to the bank. The borrower’s debt to the bank is familiar and easy: it stays with him or her (or ‘it’ if the borrower is a corporation) until it’s repaid.

The only difficult bit to get one’s head around is: What happens to the debt from the bank to the borrower? Answer: it becomes money.

That sounds counter-intuitive: ‘the debt from the bank becomes money’. But it’s the very essence of banking. If I have ‘money in a bank account’, it means simply that the bank owes (promises to pay) me money. The numbers in my bank account indicate how much the bank owes me. If I pay someone, I arrange it so the bank owes the other person some of that money, instead of me. When payment is made, the bank simply moves numbers from my account into the other person’s account. The other person feels paid – they have been paid! That is how banking works – and how it always has worked. Debt owed by a bank circulates among people, and becomes money. ‘We the people’ are happy to use it as money, because it is convenient and because banks have, in the past, put some of their massive profits into making their services cheap to use.

This leads to the theme of how the law supports banking. Banking was, and still is, very distinct from money-lending. Banking creates money: money-lenders lend money which already exists. For many centuries, banking was practiced as a series of agreements between consenting adults (so to speak). Those consenting adults were the rich and the powerful: merchants and bankers, monarchs and princes. What allowed banking to really take off, and to permeate the lives of all of us, was a piece of legislation passed in England in 1704 and later adopted piecemeal across the world, which made debt into a commodity that can be bought and sold. In the context of banking, this means that if I pass some of a bank’s debt to me, on to you, in exchange for something I want to buy from you, the law will support you when you claim that the bank now owes that money to you.

The law which authorised the buying and selling of debt was the Promissory Notes Act of 1704. It was brought in specifically to put the stamp of legitimacy on money created by banks.

Many lawyers, including the then Lord Chief Justice Sir John Holt, were against the new development: they considered that a loan of money was a private agreement between two persons, not an asset to be bought and sold. But Parliament consisted of rich men voted in by other rich men, and it overrode the lawyers. The public justification of the parliamentarians was that new credit-money, created by the Bank of England (founded in 1694), was already enabling the King to go off to war: it was a good development, and the law should catch up. The private attraction was that members of Parliament were already using bank-money to get even richer. When other countries saw the power the new law gave to the English government and to English speculators, they passed similar pieces of legislation. Today, we are living with the ever-worsening, and ever more global, consequences of that development.

2. Vested interests

This in turn leads to vested interests, and the question: ‘Who profits from banks?’ The answer is the same today as it was in 1704. Bankers, obviously; but they are not the only, or even the most significant, ones. Governments get a double advantage. First, they may borrow newly-created money from banks, charging interest and repayment to their citizens without previously asking permission. Second, citizens themselves are more prepared to lend, if in return they get an acknowledgement of debt – a bond – which they can sell. National debts in every nation date back to when that nation adopted laws to enable the buying-and-selling of debt. This piling up of debt upon citizens is especially unnecessary, even monstrous and obscene, now that money is almost all (97%) created digits. Governments may just as easily create these digits themselves without indebting their citizens. The bugbear of inflation can be avoided by the simple mechanism of not creating too much!

Financial predators also get an advantage: they may borrow money, newly-created out of nowhere and often in huge amounts, merely by convincing banks they will make a profit. This makes a mockery of free-market capitalism, which properly consists of two elements: savings (or accumulated profits) and entrepreneurship. On the one hand, savings are dwarfed by newly-created money: they have become almost irrelevant in the huge game of financial acquisition. On the other hand, the efforts of entrepreneurs are often swallowed whole, by predators armed with money conjured out of nothing.

In the current system, it is fairly obvious that government and financial predators effectively form an oligarchy. In these circumstances ‘democracy’ is merely an illusion similar to that exercised by a snake-charmer over a snake.

At this point, we can take half-a-minute or so to indulge in an unfashionable emotion: sympathy for banks – if only to highlight their role in the system. Banks may easily go broke because their debts – or liabilities, as they like to call them – stay out in the world, changing hands as payments are made. Their debts only get less, paradoxically, when a borrower pays back a debt, thereby cancelling out both debts at the same time in a reverse-process of how they were created. But borrowers may default on their debts. Sometimes lots of borrowers default at the same time in one catastrophic collapse. Banks are then in trouble: they owe huge amounts of money, but much of the money owed to them in return has disappeared. Instead of reforming the system, governments rush to their aid, charging their citizens with a big bill for re-setting the system.

To say this way of creating money is odd, unnecessary and unjust should be like saying ‘the earth is round’ – except that it is so little-known, it is almost a secret.

What (in addition to the above) are the negative effects of creating money this way?

The main characteristic of bank-money which distinguishes it from other forms of money is that it is lent into existence and destroyed upon repayment. This means that all bank-money is lent at interest: Someone, somewhere, is paying interest on every bit of bank-money in existence. Given that bank-money is now 97% of the money supply, those interest payments are hardly insignificant. They have contributed substantially over the years to inequality across the world, where today (according to Oxfam) the world’s 85 richest people own as much as the poorest 3.5 billion.

I will illustrate some of the other workings of bank-money with examples:

Take the arms industry. Governments like, and in some cases need, to compete with each other in arms acquisition. Banks happily finance this competition: they create money for governments, because repayment is guaranteed out of taxes. They are also happy to fund arms manufacture because if demand is guaranteed, a profitable outcome is more likely. The result is new money, created behind closed doors, funding a circle that’s vicious for almost everyone. Governments and their covert agencies bristle with expensive arms: their victims must be counted in millions.

Nearer to home, a domestic example: London property. In a rising market, banks happily create new money to lend: they feel secure that the loan will be repaid. New money fuels rising prices: speculators profit, and everyone else is relatively poorer. So much so, that most young people in London today cannot dream of owning the house in which they live.

Noticing how bank-money fuels inequality leads naturally to considerations of boom-and-bust. Booms-and-busts appeared historically soon after banking was legally-authorised, starting with the South Sea and Mississippi Bubbles (both 1720). The pattern has stayed the same ever since. During a boom, money is created in huge quantities for investment and acquisition. The monetary assets of the rich, inflated by new money, become absurdly vast. The assets of the majority dwindle in comparison: they cannot afford to consume enough to make existing capital profitable, let alone for the creation of more. Recession follows. The incomes of workers are further eroded by unemployment, as unprofitable businesses collapse. A vicious circle sets in. At this point, the assets of the rich must also shrink if they consist of productive investments: only speculative hot air and puff will produce profits (an example is the London property bubble referred to above). This kind of economic collapse all-too-often leads to totalitarianism and war: the twentieth century provided enough examples of that, for us all to hope that the need for monetary reform will be noticed soon.

Lastly, we might notice the plight of poor nations vulnerable to predators masquerading as free-market capitalists. Western banks create money in vast quantities to buy up land and other assets, for profit in Western markets. The effects of this are very wide: governments are corrupted, displaced peoples migrate (or attempt to migrate) to where the money is, in search of survival. The potential for a fairer, more just and prosperous world is squandered. Much more could be said about this process, so vast and damaging to the human race, and to prospects for our future.

Mention should be made here of a smokescreen which has had a remarkably long life, considering its fraudulence: respected authorities (as well as cranks and crackpots) have blamed ‘the Jews’ for secret management of international finance, and many ordinary people have absorbed the lie. Banking emerged in modern Europe from Christian attempts to sidestep the laws against moneylending. For three centuries of its legality, and for several centuries before that, banking was a protected Christian activity, defended by social exclusion and by the compulsory taking of Christian oaths. Today, the Christian Church is influential in many countries which are hard-hit by predatory finance. Enlightened discussion about how money is created might find a toe-hold in those countries: and yet Christian organisations, when discussing the crisis of debt and inequality, will not discuss the role of banking. The current head of the Church of England, for instance, defends ‘good banking’ and attacks the relatively honest – or at least not duplicitous – trade of trade of lending existing money. To be sure, the poor should be protected from rapacious loan-sharks, but it is hypocrisy to pretend that banks will ever lend to the poor. As the comedian Bob Hope said, “A bank is a place that will lend you money if you can prove that you don’t need it.” At the moment, laws privilege the rich, enabling them to borrow newly created money cheaply. Justice would be better served by taking that privilege from the rich and giving the poor more legal protection from moneylenders.

I have made no mention of more outrageous forms of value-creation such as derivatives and shadow-banking, all of which depend upon creating, selling and buying debt. Nor have I mentioned the strange relationship between war and bank-money; nor how bank-money creates an insatiable need for growth, which leads to pollution, climate change and destruction of the environment; all these will be dealt with as the book progresses.

Adam Smith, godfather of economics, wrote that ‘All for ourselves, and nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind.’ It is the job of every generation to restrain those who would be their masters – or to take the consequences.

I have not yet mentioned the vital question of how reform might be undertaken. The obvious starting-point is to reform those laws that allow debt to become money. The two websites simultaneously publishing my chapters, Positive Money and The Cobden Centre, both have strong ideas of how this should be done. I will consider these in due course: for the time being, enough to say: we should do it!