UKEU

18 February 2026

March 20, 2024

Countries experiencing lower inflation boast a combination of more active governments, lower dependence on fossil fuels and real conversations about the role of corporate greed

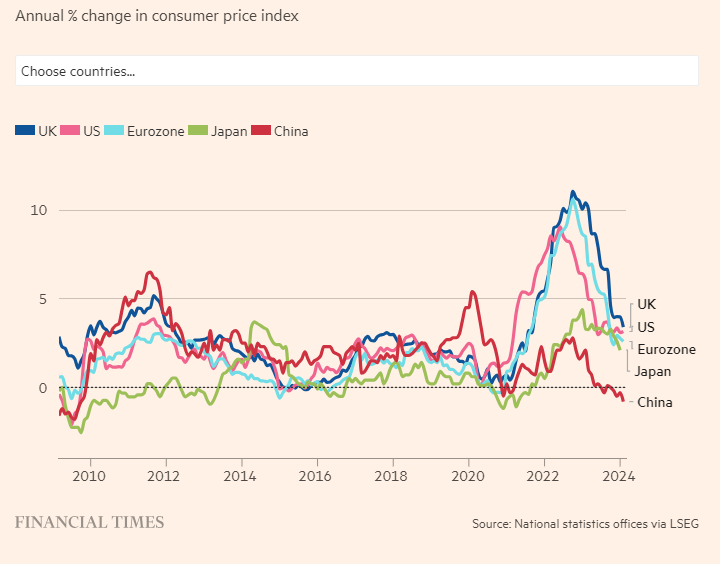

Today, it was announced that inflation fell to 3.4% in February, having peaked at a 41-year high of 11.1% in October 2022. The government heralded this as a resounding success for its “plan”, which has consisted solely of supporting the Bank of England’s interest rate-hiking regime as the solution to our inflationary woes for its entire run.

Before, during and since its 14 consecutive interest rate rises, the Bank of England has conceded that it couldn’t do anything about the high international price of gas driving inflation, that it expected high inflation to be temporary, and that the fall in inflation we experienced in 2023 was largely caused by the drop in global energy prices. It seems, therefore, that the Bank raised rates simply to show that it was doing something about soaring inflation, rather than because it thought its actions would actually be effective.

Interest rates are a policy response characterised by placing the responsibility for higher inflation on the actions and behaviours of workers and consumers. Understanding the true, supply-side roots of persistent inflation won’t undo all those needless interest rate hikes. But, revealing the inaccuracy of the rhetoric used to justify them might illuminate why the cost of living still proves unmanageable for millions despite superficial falls in inflation.

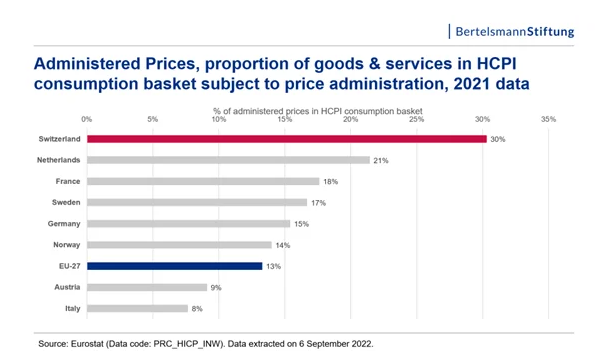

In our latest report, ‘Inflation as an ecological phenomenon,’ we found that countries which experienced comparatively low headline inflation rates tended to have one or both of the following: high levels of energy independence and strong price regulation.

The best example is Switzerland, whose inflation peaked in the summer of 2022 at 3.5% – even lower than ours is now. Due to Switzerland’s relatively low dependence on fossil fuels (around 60% of domestic electricity production is from hydropower and 29% from nuclear power), the country was better insulated than its neighbours from the spike in the gas price when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. The Swiss government also subjects 30% of goods and services to price controls, which prevents corporate profiteering (or ‘greedflation’) on the essentials.

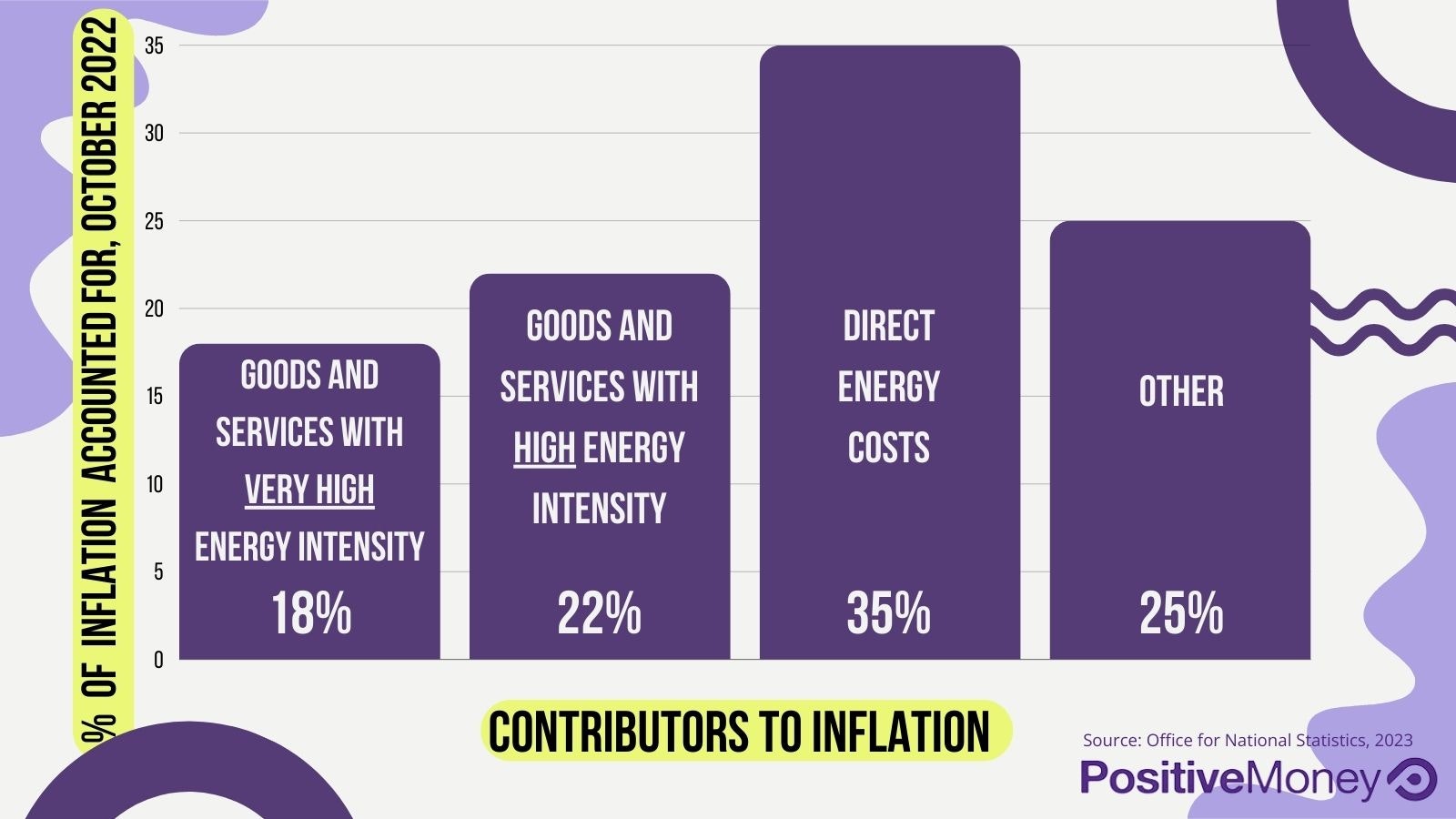

The UK economy, on the other hand, faced a particularly challenging recovery, the IMF warned last January, because of our “high dependence” on expensive gas. Compared to the Eurozone, where energy costs directly or indirectly contributed 60% to peak inflation, energy costs contributed 75% to UK inflation when it was at its peak (see graph below). We also only got one price cap, in the form of the Energy Price Guarantee, which campaigners cautioned was not bringing energy bills down enough.

Price caps are an inflation management tool for governments, not central banks. With that in mind, it’s not really surprising that the UK government didn’t apply price caps to other basic goods and services, since it outsources the management of inflation solely to the Bank of England and supported the latter’s rate hikes. The government endorsed rate hikes in spite of the Bank’s own admissions that supply-side factors were causing inflation. Even when the Bank did blame demand, urging workers not to ask for pay rises in case they stoked inflation, it did not lead by example, paying out millions in bonuses to its own staff.

Which is it @bankofengland ?

You can't blame pay rises for inflation then pay out the most bonuses you've paid in four years to thousands of your own staff.

This move proves it once and for all: workers aren't responsible for inflation.

It's being driven by global factors. pic.twitter.com/lwj4K4fqID

— Positive Money (@PositiveMoneyUK) March 11, 2024

Nonetheless, pushing that narrative enables the government to remain inactive: if the rate hikes work, they can say they supported the Bank’s demand-suppressant all along, and if they don’t, well it wasn’t the government that raised them.

For a different narrative on inflation, New Economy Brief recently analysed the situation across the Atlantic, where things are being done differently. Yes, the US central bank has raised interest rates like ours. However, the US government hasn’t used this as an excuse for inflation inertia. On the contrary, the Biden Administration opted for intervention to boost the supply side of the economy, and despite the outcry from opponents, this appears to have worked.

These actions were enabled by a very specific narrative choice: from the onset of the cost of living crisis, Biden has been clear that profiteering from corporations was a core driver of inflation. By not blaming households, the US government has been able to push ahead with public spending, including investment in renewables by way of the Inflation Reduction Act, which will ultimately shield the public from price shocks down the line. Furthermore, recognising the true role of greed in this crisis has allowed the government to strike against it: there was even a bill introduced last month aimed at stopping “shrinkflation” (i.e. when companies make their products smaller but don’t reduce/raise the price).

Clearly, relying solely on central banks to manage inflationary shocks does not deliver the outcomes we need to maintain decent living standards. Rate rises have increased the housing costs of millions already struggling to heat their homes and feed their families. There is so much this government could have done to prevent 11 million people experiencing food insecurity this January, and six million households remaining in fuel poverty.

Economist Isabella Weber – who’s opposed rate hikes since they started because they don’t address ‘sellers inflation’ – has been calling for price controls throughout the cost of living crisis. Her latest research finds price controls are the “optimal policy choice” in response to price shocks, from both an economic and social standpoint. It’s hard to imagine 11 million people would be experiencing food security if we had effective caps on the essentials.

We need a government willing to challenge corporate profits in order to achieve this; one prepared to acknowledge the role of fossil fuels in this price crisis, and therefore take steps to shift our economy to one powered by homegrown renewables.

But these policy changes won’t happen without a narrative change. We need to start demanding more of our government, and calling out distraction tactics. Whilst Biden puts ‘greedflation’ at the heart of his re-election campaign, our political discourse is dominated by culture wars issues, with little focus on soaring rents or growing food bank usage.

We must collectively resist diversions and challenge conversations from our leaders that don’t address why millions have literally been left out in the cold. It’s not like nobody is talking about greed – in December the Competition and Market Authority (CMA) found that food supplier brands had been raising prices at a higher rate than their costs had risen. Just last month, Bank of England rate-setter Catherine Mann said that rich consumers were making it harder to tackle inflation, because their spending habits are essentially protected from the impact of higher interest rates. In fact, higher rates can even boost the incomes of wealthy savers.

It is up to all of us to ensure that these discussions don’t fizzle out. Keeping the conversation alive is the only way to keep the pressure on, and force the government not to just say more, but do more to support households experiencing the worst decline in living standards of the whole G7.

Sign-up to our mailing list or follow us on X (formerly known as Twitter) for regular updates about our work fighting for a money and banking system that enables a fair, sustainable and democratic economy.