UKGlobal

27 January 2026

August 10, 2023

Momentum is growing for a windfall tax on banks in the UK, with Italy this week following Spain in adopting one. But there is uncertainty about how such a tax would work and how much it could raise. We explore a few potential options.

Since last year, we have been advocating for a windfall tax on the record profits banks are making from higher interest rates, which are more than 700% higher than in 2020. These profits are a true windfall made at the public’s expense, as they are derived not only from banks failing to pass higher rates onto customers, but also the fact the Bank of England is paying tens of billions of pounds a year in interest on banks’ risk-free reserves.

Our demand has drawn support from a number of MPs so far, and our action outside the Bank of England last week made a big splash in the media. On Tuesday Italy became the latest country to unveil a windfall tax on banks, following in the footsteps of Spain and others, with the announcement of a 40% levy grabbing headlines.

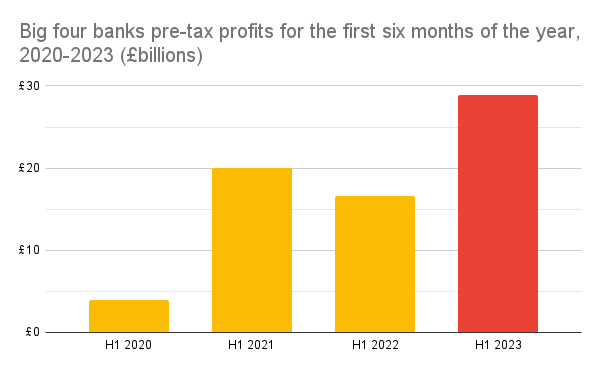

On first impression a 40% windfall tax sounded huge. We had previously called for the existing UK bank surcharge, which the government has actually cut by 60% (from 8% to 3%), to be raised to 35% in line with the windfall tax on energy companies. Based on the huge pre-tax profits reported by banks so far this year – nearly £30 billion for the first six months of 2023 – a 35% tax could be expected to raise more than £20 billion from the big four banks alone – equivalent to around £720 per household. A 40% windfall tax would raise £23 billion – more than £815 per household. We put forward a few ideas for what this could be spent on:

@positivemoneyuk

If the #uk government imposed a windfall tax on #banks profits like Italy just has, we could generate billions for public sector pay rises, free school meals, nationalising energy companies and pulling families out of poverty. #costofliving #costoflivingcrisis #news #learnontiktok

The details of how the Italian scheme would work were however unclear. At first it was simply reported that this would be a 40% tax on banks’ net interest income (NII) – the difference between the amount banks receive from their lending and the amount they pay to those they borrow from (i.e depositors). The four biggest banks in the UK – Lloyds, Barclays, Natwest and HSBC – reported a combined NII of £23.5 billion in the first half of this year, suggesting a 40% tax on NII could raise around £20 billion in 2023. This would be enough to reverse cuts to universal credit, abolish the two-child benefit cap, provide free school meals to all children and give public sector workers a 10.5% pay rise. Alternatively, it could fund a 2.5% cut to VAT, which would also help reduce inflation.

After a morning of confusion, the Financial Times reported that the 40% levy would actually be based on the difference between NII in 2021 and the figure for 2022 or 2023, whichever is larger. This would of course raise much less money. In the UK’s case, based on this year’s results so far, we can estimate the difference between NII for the big four banks in 2021 and 2023 was £13.89 billion, so the revenue generated by a 40% tax would shrink to just £5.56 billion. It is also worth noting that UK bank profits in 2021 were also higher than in previous years, perhaps as a result of Covid support being designed in ways that benefitted banks.

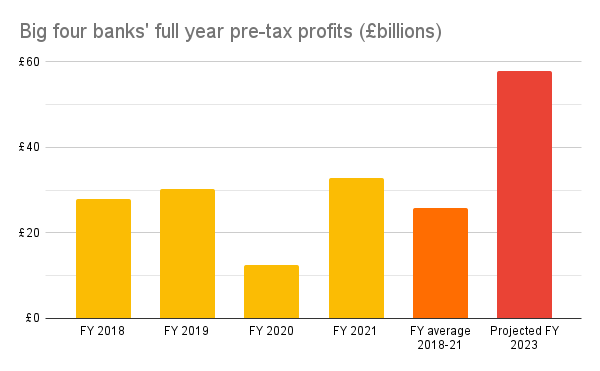

Sadly, Italy’s windfall tax plan has undergone further watering down after a fall in the share prices of Italian banks, with the tax being capped at 0.1% of total bank assets (such a cap would still allow around £13bn to be raised in the UK). However, we shouldn’t just look to Italy for inspiration for a windfall tax on the banks. The Czech government has introduced a 60% windfall tax on bank profits exceeding 120% of the 2018-21 average, which we can estimate could raise £18.42 billion from the big four UK banks in 2023 based on profits reported so far.

We can also look closer to home. In a similar context to today, where the economic situation was dire, while oil and gas companies and banks were recording huge profits, the Thatcher government introduced windfall taxes on both of these sectors. As Thatcher, hero of the City of London, put it in her memoirs:

“We had in November announced extra taxation on North Sea Oil and Gas profits. The question now was whether to levy a windfall tax on bank profits. Naturally, the banks strongly opposed this; but the fact remained that they had made their large profits as a result of our policy of high interest rates rather than because of increased efficiency or better service to the customer.”

The windfall tax introduced in the 1981 budget was a 2.5% levy on non-interest bearing deposits. It raised £400 million – equivalent to £3 billion in today’s money – according to the Institute for Government.

The Bank of England’s latest data shows there are around £450 billion of non-interest bearing deposits which could be eligible for such a tax today, with around £270 billion held by households and £180 billion held by non-financial firms. A 2.5% tax would therefore be expected to raise more than £11 billion – equivalent to nearly £400 per UK household.

Interestingly, a tax on non-interest bearing deposits bears some similarity to the idea of an unreserved deposit tax put forward by Eric Breon as an alternative to paying banks interest on reserves to set a floor on lending rates. If set at the same rate as the base rate – currently 5.25% – this would raise more than £65 billion a year in the UK. This could be enough to power every home in the UK offshore wind, a cost that was estimated at £50bn in 2020.

Some critics have argued that taxing banks would do more harm than good, citing the “cost” it incurred on banks’ share prices in Italy. Yet reporting falls in share prices as “costs” is disingenuous, as these are paper losses that are only realised if investors are to sell.

Others from the financial sector have argued that we shouldn’t meddle with windfall taxes as the negative impact on banks’ share prices could hinder their ability to lend to the economy. Not only do banks already neglect the needs of the real economy, but this is very weak grounds for the public being expected to pay the price for such exorbitant profits during a cost of living crisis. Furthermore, by this logic, we should expect to see an explosion in lending anyway, as profits increase banks’ capital. Ironically, reducing bank lending is one of the ways central banks hope higher interest rates will reduce inflation. If true, taxing banks would therefore be complementary to central bank policy.

Regardless, getting hung up on the ups and downs of share prices, which are often detached from economic reality, is a distraction that hinders efforts to redress the balance of wealth and power in the economy. Properly taxing banks’ windfall profits would raise billions of pounds to help people get through the cost of living crisis. But beyond that, we also need to build a financial system in which we are less dependent on a handful of big shareholder-owned banks to meet the needs of society.

If you haven’t yet, add your name to our petition to #TaxTheBanks here.