UKEU

18 February 2026

August 1, 2023

The housing system has been in chaos over the last 6 months, as escalating rents, interest rate hikes and softening house prices upend an already-fragile system. We break down the latest data to explain what’s going on – and why tackling the financialisation of our homes would provide a more permanent route to a safer, more dignified and affordable housing system.

House prices are softening and sales low

What: house prices are dipping.

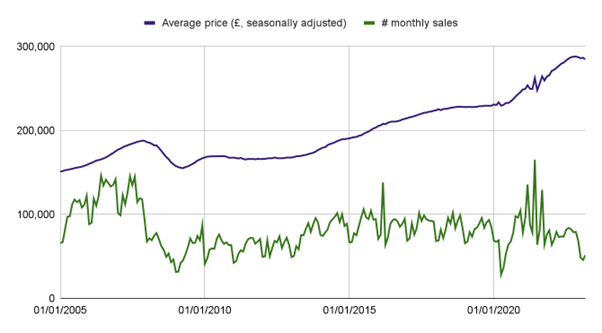

After two decades of near uninterrupted climbing – including a significant uptick during the pandemic – house prices have begun to soften. The latest government data indicates that average UK house prices in May were lower than in November 2022 (by around £3,000, adjusting for seasonal changes, a drop of 1%). There has not yet been a dramatic drop but given consumer price inflation has been running at over 5%, it’s true to say that house prices have not been increasing at quite the dizzying speed they have been in the last decades.

Why: interest rate rises.

The Bank of England has been consistently raising interest rates in a bid to bring down inflation. This is despite the fact that wages are struggling to keep up with inflation, and that inflation is rooted in supply-side issues (such as worker shortages and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine increasing energy prices) as opposed to ordinary people spending too much. This has meant that the cost of mortgage interest has risen, making it harder for people to buy homes.

What’s needed: long term house price stability goals.

Because our homes have been transformed into financial assets that are bought and sold to store and generate wealth, they have become particularly sensitive to changes in interest rates. When interest rates are low, mortgages are cheap, so house prices soar. When interest rates are raised, prices can plummet as people struggle to afford to keep up with their mortgage, or don’t want to take one on. We need a long term government plan to remove this boom and bust cycle from the housing market, by definancialising housing and ensuring prices stay stable, and affordable relative to incomes. The UK Government should launch a long-term housing affordability strategy to tackle these systemic causes of unsustainable house price inflation. This should set the path for a long-term transition to stabilise house prices and bring the house-price-to-income ratio down to more affordable levels over time. Alongside this, the Bank of England’s main policy making committees, the Financial Policy Committee (FPC) and Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), should support the government’s goal of lowering house price inflation as part of their secondary objectives. Read more here.

The rise in cash buyers

What: the proportion of people buying homes without a mortgage is increasing.

Typically, between 50,000-100,000 homes change hands every month. In 2023, the reduced demand for buying homes meant this dropped to around 35,000 (see figure 1). This has included a drop in the number of cash transactions, but not as big as the fall in mortgage buyers. As a result, the proportion of home sales to cash buyers – individuals or companies wealthy enough to buy homes without a loan – has ticked up, rising from around 25% of buyers to over 30%. This means a growing portion of the building stock is being transferred to this wealthy group.

Why: the rich are able to buy during the housing market dip.

According to Savill’s, wealthy cash buyers bought 71% of homes in prime central London locations between January and May this year, compared with 61% in the same period of 2022 – many being overseas investors. Outside of London, Knight Frank has commented that ‘the list of areas where cash buyers are most prevalent has a distinctly second-home feel’, and noted that high levels of cash buyers are correlated with areas with high levels of retiring homeowners – ‘downsizers’, who use the value of their previous home to pay for a smaller home outright. The cash-rich are able to take advantage of the housing market dip to expand their property portfolios at discounted prices, without being constrained by higher interest rates like those buying with mortgages would be.

What’s needed: fair taxes on second homes, overseas non-residents and investment properties.

At the moment, capital gains tax applies when homes are sold that the owner doesn’t live in as their primary residence, but this urgently needs reforming. Furthermore, for high rate taxpayers and company owners, the capital gains tax rate is lower than what they would pay on income from work. Capital gains tax bills can also be reduced significantly for many through inflation adjustment, claims that the owner lived there for a period, expenses and mortgage interest deductions and company incorporation to use lower tax rates. Overseas investors can claim that their home is their main property, thus avoiding capital gains tax completely. Reforming capital gains taxes would raise funds for the public purse while disincentivising speculative investment in our homes by people who won’t live in them. Tax Justice UK, for example, estimates that equalising capital gains and income tax rates would raise £15.2 billion a year.

Escalating rents

What: rental costs are soaring.

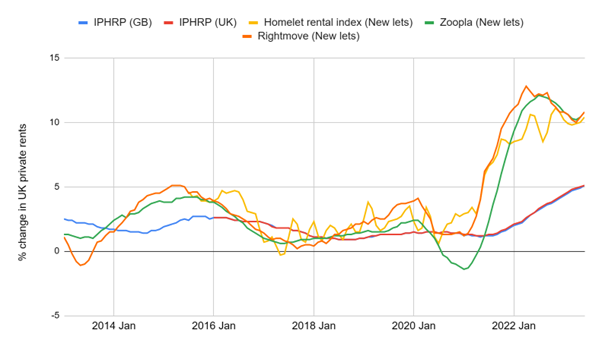

The cost of renting privately – already higher than the cost of social rent and mortgage repayments as a proportion of income – has escalated in the last 12 months. In the last year the cost of new lettings has increased 10-15%, with the cost of renting as a whole increasing about 5%.

Why: a dearth of genuinely affordable living situations and rising interest rates.

Last year, there was a surge in demand for rental homes as people began to move after the pandemic. This short-term surge collided with a longer-term situation whereby people have been increasingly unable to rent socially (due to a decline in the number of council homes) or buy (due to long term house price increases). This is not, in most places, due to a sudden physical shortage of overall building space – today there are 0.44 homes per person in England, compared to 0.41 homes in 1991, and homes have become slightly less crowded in the last decades – but a lack of genuinely affordable homes trapping too many people in the PRS. Without rent stabilisation policies, landlords have been able to hike rents in response to this demand. This has escalated the disruption because it forces renters, already paying more than they can afford, to move, increasing rental inquiries. There’s some evidence that landlords are now passing on interest rate rises to tenants too.

What’s needed: a better deal for renters, and investment in social homes.

Better rights and protections for private renters are urgently needed, including ending no-fault evictions, requiring privately rented homes to meet the Decent Homes Standard and energy efficiency standards. Rent stabilisation and controls were in place in Britain for most of the C20th and would protect renters from uncontrolled rent rises. Investing in council homes, for example through Right to Buy Back schemes, and supporting the development of community-led homes would enable more people to move to homes affordable for them, reducing the demand for privately rented homes.

Increasing reliance of the economy on homes

What: further decreases in lending to the real economy.

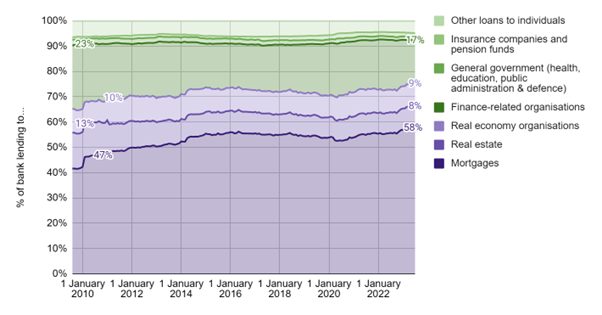

The share of lending going to productive non-financial businesses (the ‘real economy’) – like manufacturers, agricultural organisations, construction companies and more – has been falling rapidly since the 1980s, down from 23% in 1986 to only 8% of all bank lending in recent years. In June 2023, mortgages hit 58% of bank lending, the highest it’s been since at least 2009, the earliest date that the Bank of England releases this data for. This has occurred while the overall amount that banks lend has steadily increased- hovering around £2,500 billion since 2020.

Why: homes turned into assets.

The liberalisation of the financial sector since the 1970s triggered a shift in the role that retail banks played in the British economy: they transitioned from mainly lending to the real economy for productive investment to primarily lending to finance the purchase of homes. Not only does mortgage-based credit creation increase house prices and thereby investor interest in homes, the easy and low-risk profits it offers means companies and activities that would actually create new value are neglected by banks.

What’s needed: diversify the banking system and introduce credit guidance policies.

Creating new public national and local development banks, as well as community and stakeholder banks, could better allocate credit to meet the financial needs of communities, small businesses and the real economy. Whereas the business models of commercial banks are based on maximising profits for shareholders which has led to an over reliance on mortgage lending, the ‘stakeholder bank’ model, common in countries like Germany, seeks to provide both social and economic value which often has positive spillover effects for local communities and local economies. There is also a role for the Bank of England to strengthen existing macroprudential tools to help achieve sustainable house prices by dampening expectations of house price inflation and regulating the supply and direction of bank credit towards more socially useful activities – like home retrofits, new clean energy infrastructure, or buying back council homes.

If you haven’t yet, sign-up to our mailing list for more regular updates on our research + campaign work.