Finance and DemocracyUK

18 December 2025

June 7, 2023

Homeownership in the UK is on average safer, more affordable and better quality than renting. But due to high upfront property prices, swathes of the population are unable to choose whether they rent or buy. Dan Goss, a researcher at Demos, highlights that this is a crisis that is being passed down through the generations.

Talk of a housing crisis is becoming ever more common in Britain. It was reported last month that six and a half million people in the UK are now living in poor quality housing. Meanwhile, stories of the long queues to view flats or people offering huge amounts of rent up-front are regulars in the news. Many people strive to buy a home to avoid this, with owned homes tending to be more affordable and higher quality than rented ones. Yet, this typically costs people in England around nine times their annual earnings, or 15 times in a typical London borough. For many, the crisis therefore ends up as a long struggle towards homeownership.

Some experience this struggle more than others, however – and it matters what family you were born into. Positive Money’s recent analysis highlighted how ethnic minority groups are significantly less likely to own a home than White British people – a disparity which has been carried over from generations prior. Previous research has also shown that young people whose parents aren’t homeowners are much less likely to become homeowners themselves.

A range of factors play into this generational disadvantage, but a key part of the story is inheritance and gifts. Between 2021-22, over a quarter of first-time buyers were helped by financial gifts from friends and family, with some polls suggesting that as many as six in ten of homebuyers under 35 are getting help. Given this, over a quarter of prospective buyers say the only way they could buy a home is by receiving inheritance. So while the people getting these transfers are given a step up to homeownership, others are left to navigate – and fight for – what’s left. Inheritance therefore acts as a gatekeeper to homeownership.

In a shift in the narrative, however, it has been suggested we might be reaching the peak of property inheritance. The Times recently published data showing that the percentage of estates that contained property fell from 75% to 73% between 2019 and 2020 (financial year end). It projects this to continue – to drop another 7% by 2030. This makes sense; as explained by a real estate analyst in the article, the people who are dying – and then passing on inheritance – are increasingly born after the boom in homeownership that followed World War 2.

So, is inheritance quitting its role as gatekeeper to homeownership? To answer this, we have to understand what it means for property inheritance to be falling; this is not just about the proportion of inheritances containing property. There is clearly another important factor: how much those properties are worth. And this matters much more.

A New Age of Inheritance

Importantly, most people who inherit property end up selling them for significant cash sums, or becoming landlords and renting out property for a monthly boost to their income. In fact, only 12% use inherited property as their primary home. What matters to the person receiving inheritance – what gives them the step up – therefore tends to be the value of the property, and other assets, that they receive, rather than whether or not the inheritance contains property in the first place.

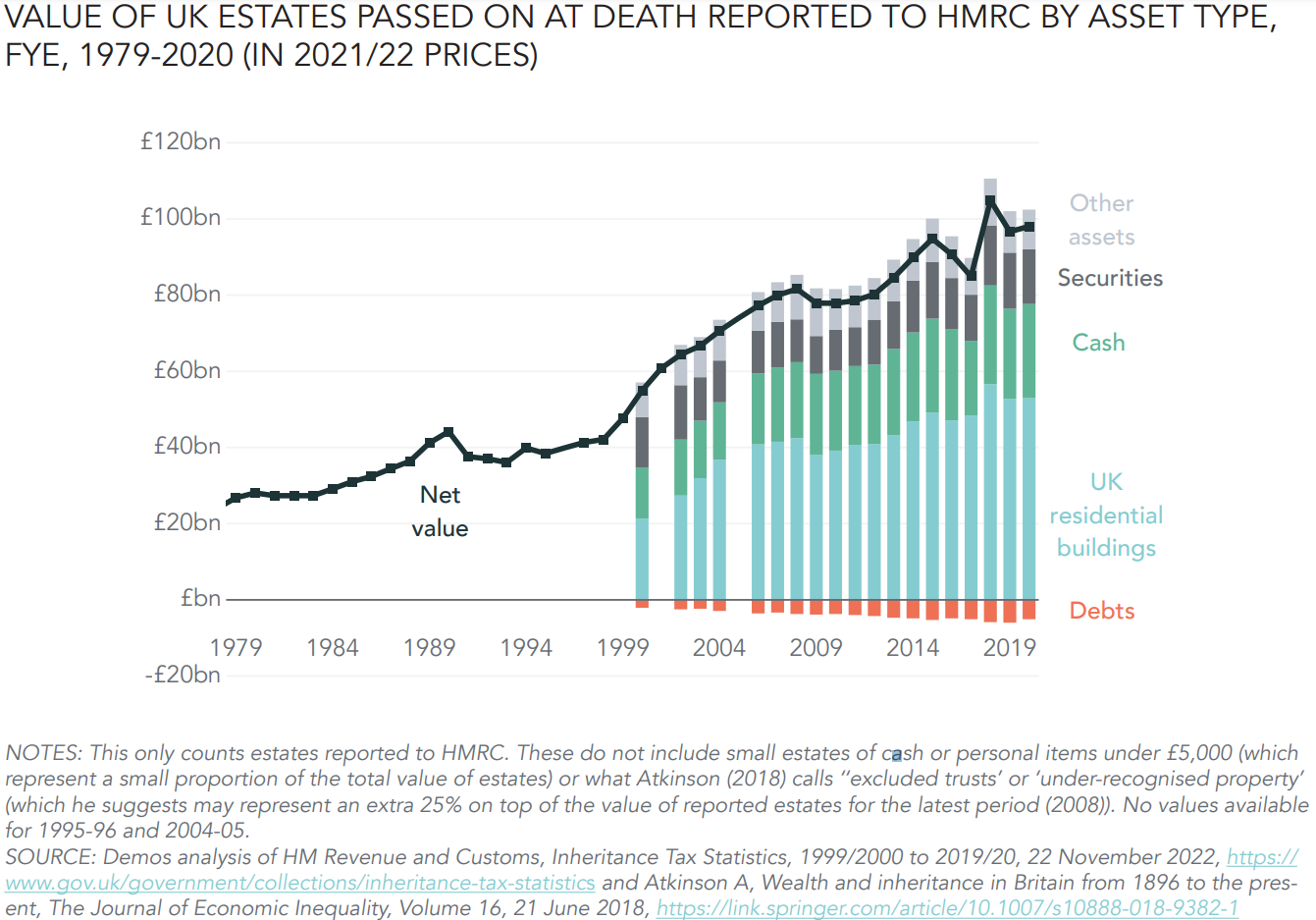

When we instead look at how much inheritances are worth, it’s a very different story. The amount passed on in total inheritances has increased rapidly in recent decades, and is expected to continue rising in those to come. While the proportion of inheritances containing property is expected to fall 7% this decade, the value of inheritances passed on annually in England is projected by the Resolution Foundation to increase by around 50% in that time – and to double by 2040. It’s something we at Demos are calling the UK’s new age of inheritance.

The value of property within inheritance is also likely to continue increasing. While the value of property in reported estates fell from a high of £57 billion in 2018, it rose very slightly year–on-year in the most recent data available. And despite recent falling house prices, forecasts suggest that by the end of the decade, house prices will be much higher than their 2022 level. This is set to greatly offset the impact of falling homeownership resulting in fewer numbers of homes in estates up to 2030.

So, in the aggregate, the fact that fewer people are expected to pass on homes in inheritance is a secondary concern – the total value of those inheritances is key. But the distributional effects are a different story. With more people not passing on homes – which tend to be people’s most valuable asset at death – a larger number of the next generation will get relatively low inheritances. Homeowners, meanwhile, are passing on homes worth increasingly high amounts. This looks set to expand the divide between the children of homeowners and of renters.

Putting some numbers on this growing divide, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) modelled the inheritances of people born in the 1980s. They expect that those in households with the least wealthy parents (in the bottom fifth) will get a 5% boost to their lifetime income through inheritance. In contrast, those with the wealthiest parents (in the top fifth) are expected to get a 29% boost. This gap is stark, and will open a range of opportunities for the will-haves. One such opportunity is homeownership itself. The will-haves get a step up – above the won’t haves – when trying to buy a home.

Everyone should have the right to safe and affordable housing. Yet, not only will property inheritance continue being a gatekeeper to homeownership, the resulting inequalities are set to grow. This makes it more important that policymakers address the crippling costs of homes in the UK (while also helping to alleviate problems in the rental market). But for the ambitious housing sector reform we need, politicians, civil society and businesses need to demand policies on wealth and inheritance fit for the current day.

A lot is going to change in the UK’s new age of inheritance – for housing and beyond – and we need to start thinking seriously about how to adapt.