UKEU

18 February 2026

Positive Money’s latest report reveals the scale of the political power that big finance holds over our democracy, and puts forward recommendations to give a stronger voice to the public and civil society. The report also calls for fundamental reforms to the money and banking system, in order to align financial flows with the needs of people and the planet.

You can read the full report here. For those interested in watching the launch event in full, it can be found on our YouTube channel.

On Tuesday 7th June in Parliament, Positive Money launched a new report exposing the power banks and financial firms wield over politicians and public officials. Our Executive Director Fran Boait hosted the event, and lead author David Barmes presented the report’s key findings and policy recommendations, before opening up the floor for discussion between parliamentarians and members of the public on how to restore faith in our democracy.

New research from @PositiveMoneyUK reveals how big banks are hijacking our democracy. Please RT to expose and #StopTheBankingLobby https://t.co/P27t4Wn4EZ

— Caroline Lucas (@CarolineLucas) June 9, 2022

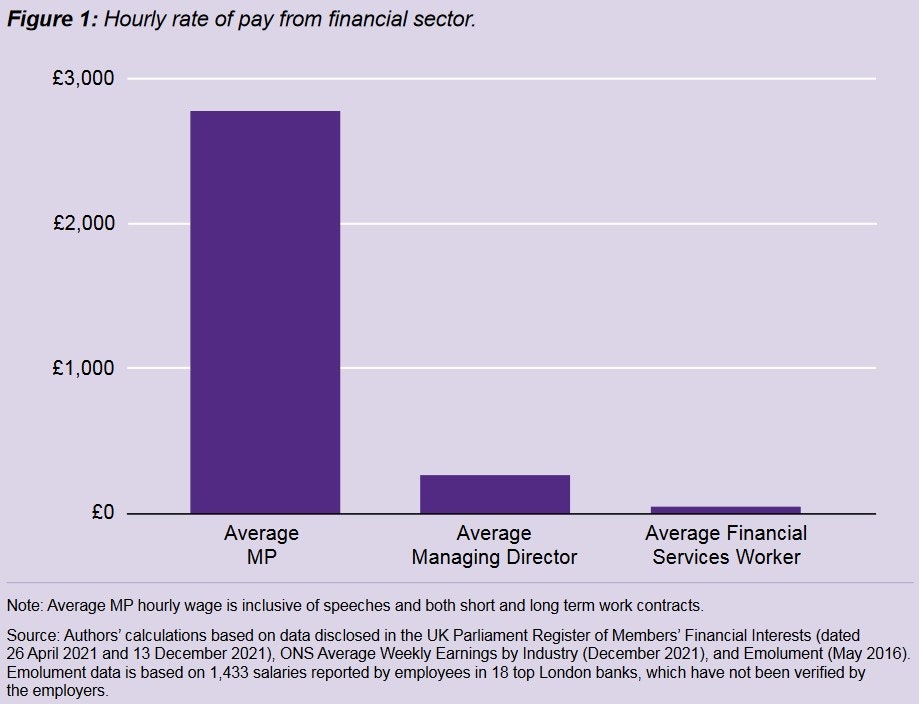

Central to the new research was unmasking the many channels financial lobbyists use to access the corridors of power. These included the better-known channels of influence, such as MPs having second jobs and delivering speeches in the financial sector, for which we found the average hourly wage was £2,738. Cumulatively, through payments for second jobs, speeches, donations, gifts and hospitality, the report revealed that financial institutions and individuals closely tied to the sector collectively spent £2.3 million directly on MPs throughout 2020 and 2021 – and this pales in comparison to the over £15 million they paid to political parties for the same period.

This trend wasn’t confined to the House of Commons, either; we discovered one fifth of peers in the House of Lords have registered paid positions at financial institutions. This number increases to over half of members when looking at the Economic Affairs Committee (a parliamentary committee responsible for investigating matters related to economics and finance), meaning that these lawmakers have a vested interest in leniency towards the financial sector.

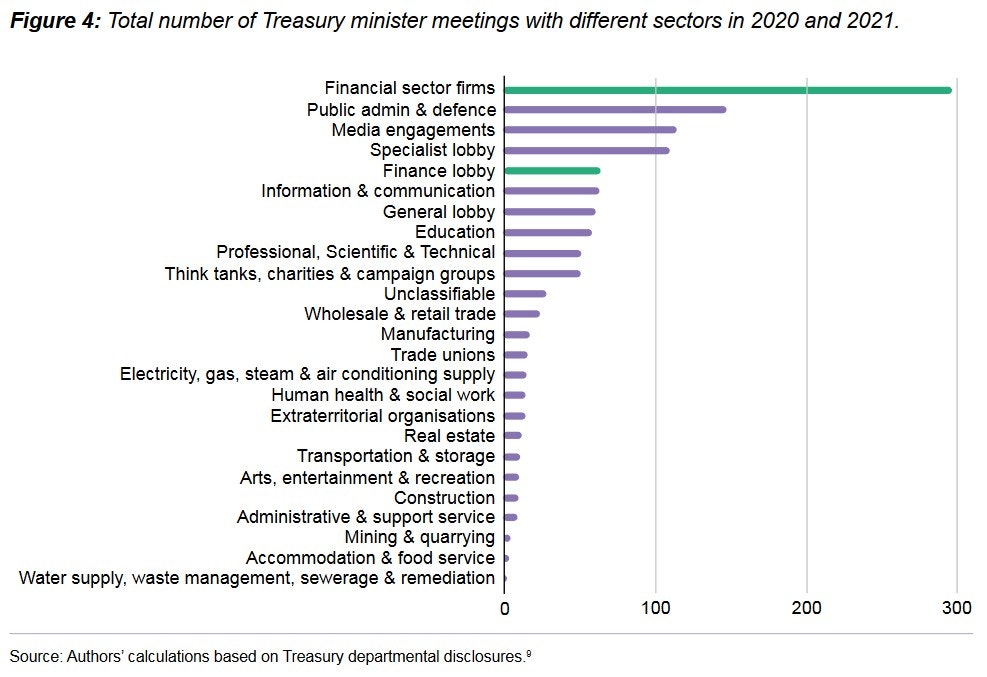

But financial ties to politicians are just one part of the picture; the financial sector also has disproportionate access to the Treasury. Of all the meetings Treasury ministers had in 2020 and 2021, over 30% of them were with financial sector firms and their lobbyists. This is significantly more than any other sector of the economy, and can’t be justified by how many people it employs. Between 2012 and 2021, lobby group UK Finance had more than 1.5 times the meetings that the Trade Union Congress (TUC) had, despite the latter representing five times as many workers.

When researching how one sector gains such significant facetime with the government, we found that over the past decade, financial institutions that hired a former UK Chancellor benefited on average from a 59% increase in meetings with government departments. Every former Chancellor for the past 40 years has gone on to work in the financial sector, despite only a third of them having worked there prior to becoming Chancellor. Taken together, these observations indicate that hires of previous Chancellors are related to the stronger political connections firms can expect to leverage.

This revolving door between the public sector and the private financial sector poses two main risks: (1) individuals coming from the financial sector showing a predisposition towards policies favourable to that sector (Adolph, C. 2013.) and (2) the knowledge that there are lucrative prospects in the sector after public office eliciting similar leniency from acting policymakers. It’s a channel of influence we likewise observed in regulators, with almost three quarters of Bank of England policymakers having worked in private finance either before, during (!) or after their terms on one of its three key committees.

The significance of these findings cannot be underplayed: parliamentarians and regulators are voting on policies and laws that directly impact their own income.

The ultimate consequence of this capture of the political process and imbalance of access to government officials is overwhelming inequality, driven by double standards in policymaking decisions. Examples include banks getting a tax cut last autumn whilst the rest of us got a national insurance hike, or the government mulling over scrapping the cap on senior bankers’ wages whilst urging ordinary workers not to ask for a pay raise – even as real wages in the UK fell at the fastest rate in two decades.

As Alison Thewliss, MP for Glasgow Central, highlighted at the report launch event, Brexit has presented the financial sector with an opportunity to use its channels of influence to revert regulation to the weak state it was in prior to the 2008 financial crash. The most notable example is the recent resurrection of a reckless policy requiring regulators to consider the “international competitiveness” of big financial firms when making and enforcing the rules – a policy widely recognised to have contributed to the financial crash.

All of this gets justified by false narratives propagated by financial institutions and their allies in government, claiming that big banks are the ‘engine of our economy’. Yet, various studies into this myth have found that limitless growth of the financial sector is not beneficial for the rest of society because, at a certain point, it starts to extract more from the rest of the economy than it contributes, so finance grows and grows while the rest of us are left behind.

Narratives like this – although widely disseminated – are fortunately not always widely believed. Our audience provided much hope on this, with over 80% of online and in-person attendees polled believing that the finance lobby’s unequal access to government meetings and the revolving door between regulators and private finance are both harmful to democracy. 95% found the lobby’s financial ties with parliamentarians to be a threat to democracy, meaning only 5% of people saw none of these connections as a threat.

The excessive power of big finance over our democracy is the main barrier to creating a fairer, more democratic and sustainable economy. To block the various channels of influence that the financial sector currently exploits, the report recommends a ban on private sector second jobs, stronger disclosure standards for public officials reporting their private interests, and longer “cooling-off” periods between public and private sector roles, amongst other things. It is our hope that in laying bare the extent of big finance’s influence over our democracy, we can spark the public demand required to make these changes a reality, and ensure the public policymaking process starts truly serving people and the planet.

You can read the full report here, or check out the coverage of it in the Guardian, City AM, and Politico. On Twitter you can find our video and thread on the report itself, and see our live tweets from the event. For those interested in watching the event in full, it can be found on our YouTube channel.

Adolph, C. (2013). Bankers, Bureaucrats, and Central Bank Politics: The Myth of Neutrality. Cambridge University Press.

Figure 1, Figure 4 — David Barmes et al (2022). The Power of Big Finance. Positive Money.