Why ‘Britcoin’ shouldn’t mean the end of cash

July 28, 2021

The government and the Bank of England are working together on developing a central bank digital currency (CBDC) for the UK. There are concerns that this new ‘Britcoin’ would replace cash, but the real war on cash is being waged by big banks and card companies.

Over the weekend the Daily Mail made a huge splash about a central bank digital currency (CBDC, or as they call it ‘Britcoin’) being part of Rishi Sunak’s plans to get rid of cash.

The Britcoin revolution! Rishi Sunak plans to replace our cash with official digital currency https://t.co/A5lG30Z6mg

— Daily Mail U.K. (@DailyMailUK) July 25, 2021

Similar fear mongering also appeared in The Spectator. The Chancellor even had to take to social media to dispel these rumours.

Not only is the timing of these articles strange (the Treasury’s CBDC taskforce was announced months ago), but they are confused interpretations of what a CBDC would mean in practice.

First of all, a CBDC would not be a replacement of cash. Cash is a physical token that can be exchanged directly between users without a centralised infrastructure, whereas the CBDC that the Bank of England is looking at introducing would be account-based. Rather, what a CBDC would be a replacement for is bank deposits – the private money created by banks when they make loans, which we currently rely on to make card payments and shop online.

The Bank of England has been very clear that a CBDC would be designed to work alongside cash, and not against it. We should therefore be thinking of CBDCs not as something that will replace cash, but a new form of public money that will complement it, allowing us to switch between physical and digital forms of public money as we choose. Even if CBDCs could allow the death of cash in theory, we shouldn’t let it mean that in practice.

Cash is a brilliant social technology. It essentially allows us to remove the barriers of space and time, facilitating the exchange of goods and services based on mutual trust, without the need for a microchip or processor in sight.

Despite the existence of this simple and accessible technology, card companies and tech giants like Visa, Mastercard and Paypal, have spent huge amounts of money trying to convince us that introducing card readers — which need to communicate with a huge chain of datacentres spread out across the world — is more convenient or efficient than settling transactions by simply swapping over notes and coins to the human in front of you.

For those trying to understand the implications of ‘cashless society’: The battle is not “cash vs. card” or “cash vs. pin” or “cash vs. mobile”. It’s cash vs. corporate datacentres

— Brett Scott (@Suitpossum) November 20, 2018

But beyond the slick PR spin of the cashless lobby, digital payments come with hidden costs that remain hugely expensive, especially for small businesses. And as the Bank for International Settlements noted in their latest annual report, these costs may increase if big tech giants capture the market:

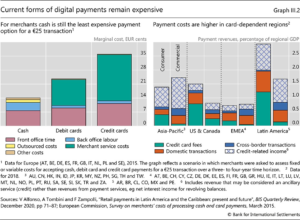

“Entrenchment of market power may potentially exacerbate the high costs of payment services, still one of the most stubborn shortcomings of the existing payment system. An example is the high merchant fees associated with credit and debit card payments. Despite decades of ever-accelerating technological progress, which has drastically reduced the price of communication equipment and bandwidth, the cost of conventional digital payment options such as credit and debit cards remains high, and still exceeds that of cash (Graph III.2, left-hand panel). In some regions, revenues deriving from credit card fees are more than 1% of GDP (right-hand panel).

“These costs are not immediately visible to consumers. Charges are usually levied on the merchants, who are often not allowed to pass these fees directly on to the consumer. However, the ultimate incidence of these costs depends on what share of the merchant fees are passed on to the consumer indirectly through higher prices. As is well known in the economics of indirect taxation, the individuals who ultimately bear the incidence of a tax may not be those who are formally required to pay that tax. The concern is that when big tech firms enter the payments market, their access to user data from associated digital business lines may allow them to achieve a dominant position, leading to fees that are even higher than those charged by credit and debit card companies currently. Merchant fees as high as 4% have been reported in some cases.”

While cash is cheaper for us, it is much more expensive for banks, which is why they’re waging a war on it. Customers’ ability to convert their bank deposits into cash means they are forced to hold more non-interest bearing cash on their balance sheet, instead of financial assets which earn them bigger profits. Banks are also required to pay for the public’s free access to cash by funding the LINK network (the UK’s largest cash machine network). It is therefore no surprise that Which? estimates banks recently saved £120 million by closing down ATMs, passing the costs onto the public instead, who were forced to pay £104 million to access cash through fee-charing cash machines in 2019.

The two companies that control the card payments market, Visa and Mastercard, have joined in the war on cash because it gives them an even bigger captive audience to force their products and services on. And big tech companies like Facebook are also getting in on the action, seeing the huge opportunities to extract higher fees and harvest our personal data from the payments system if there is no public alternative.

During the Covid pandemic, the war on cash has accelerated, with a flood of disinformation convincing businesses and consumers that cash is dangerous to use, despite study after study finding that cash poses a low risk of virus transmission, and could actually be safer than card payments (particularly larger payments that require touching the buttons on a card reader).

The Bank of England has pledged to provide cash for as long as people who want to use it. It’s not CBDC that’s threatening our ability to use cash, but the banks. The very same who stand to lose if we introduce a CBDC.