Leaders and Laggards: Keeping score of green central banking in the G20

April 15, 2021

The world’s biggest central banks and financial supervisors are all talk and no action on tackling the climate crisis. Positive Money’s latest report, The Green Central Banking Scorecard, evaluates and ranks G20 countries on their monetary and prudential authorities’ green policies and activities, and highlights the green policies they should use to rise to the climate challenge.

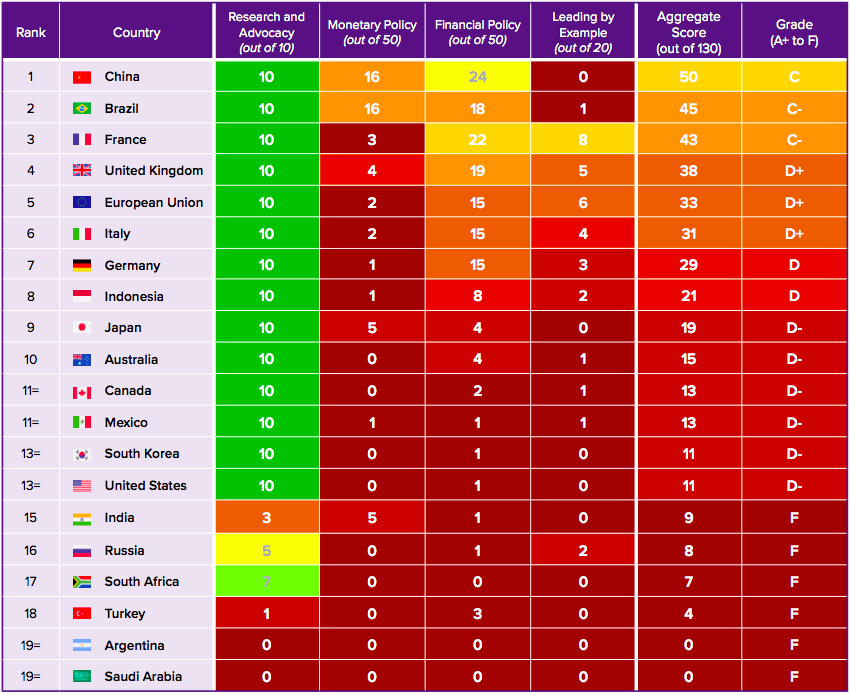

On the 31st of March, Positive Money launched The Green Central Banking Scorecard to put central banks under the spotlight and ask whether they are doing their part in preventing climate and ecological breakdown. For every country in the G20, we evaluated the green policies and activities of their central banks (and other supervisory institutions with related responsibilities). The following table shows the results, with an overall score and final grade for each country in the two rightmost columns:

China, Brazil and France have taken the top three spots in the ranking, but they all still have a long way to go before they can be considered ‘green’. The UK sits in fourth place, but is definitely one to watch this year as its monetary and financial remits were recently updated to reflect the government’s environmental priorities and net zero target. Later this year, the UK will be leading the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), so the time is right for shining a spotlight on the role of central banks in tackling the climate crisis. The Bank of England has portrayed itself as a pioneer on climate, and will be expected to show leadership over the next few months as COP26 approaches.

However, the green central banking race has just begun, and the fact that the scores are low across the board is deeply concerning: none of the G20 countries’ central banks and supervisors have implemented a single high impact green policy. Some of them have more minor policies underway, like assessing environmental risks and incentivising financial firms to make green investments, but they’re still very reluctant to make the bigger interventions that are essential for averting the climate crisis.

Creating the scorecard report was a highly collaborative process. We consulted with civil society and academic experts throughout the process, engaged in bilateral interactions with central banks and financial supervisors, and have received endorsements from 24 organisations and institutes. We would like to thank all those involved, and look forward to working with all these stakeholders and the wider movement to ensure that central banks and supervisors step up to the challenges of climate and ecological breakdown.

We launched the report with an online webinar, chaired by Katie Kedward from UCL’s Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP), that featured an international panel of experts in the field of green central banking. Our guests were Professor Yao Wang from the International Institute of Green Finance (IIGF), Danae Kyriakopoulou from the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum (OMFIF), and Lucie Pinson from Reclaim Finance, who were joined our economist (and lead author of the report) David Barmes to discuss the key insights of the scorecard and reflect on what the next steps for central banks and supervisors should be.

In the webinar, Danae Kyriakopoulou put forward that greater clarity is needed on the objectives central banks should focus on when tackling the climate crisis. One course they could take is seeking to reduce climate risks, and taking into account climate impacts on price inflation and financial stability. A more proactive approach would have central banks making an active contribution to governments’ transition efforts. The cost of not acting is much higher than the cost of acting with insufficient data.

Yao Wang argued that green taxonomies are crucial first steps, and central banks should prioritise greening policies already in place, such as central bank collateral frameworks and asset purchase programs. But in the longer term, entirely new policies and capacity building would be needed to make the green transition.

Lucie Pinson highlighted that central banks promoting green assets without phasing out fossil fuels is a clear failure, noting that not one central bank has implemented a measure to withdraw support for carbon-intensive projects. The boldest move central banks could make in 2021 would be to stop buying any assets from companies initiating new fossil fuel projects.

The wider response to the report has been very encouraging as well, with strong international press coverage, with over 30 articles (and counting!) appearing in more than a dozen countries, including the UK, US, France, China, and Korea. Multiple central banks have expressed interest in the report, and the Brazilian central bank even tweeted about it. This shows that while central banks and supervisors in G20 countries still have a long way to go, public pressure is mounting on them to take on the climate challenge.

Positive Money will update the scorecard in the future. When the time comes, we’ll reveal which countries have risen in the ranks in a second edition. There are early signs of a ‘race to the top’ emerging among central banks to green their operations, and it remains to be seen whether the current frontrunners can maintain their lead, especially if they rest on their laurels while others accelerate their efforts. We look forward to keeping score and holding the world’s most powerful central banks to account.