Securitisation is back, and green finance must stray far away

Securitisation played a central role in the 2008 crisis. Yet it’s been making a comeback, and green finance is getting involved. Here’s why securitisation should have no place in green finance.

What is securitisation?

Securitisation is the process of packaging illiquid financial assets together into tradeable financial instruments, known as asset-backed securities (ABS). Various types of ABS are then sold off to investors, freeing up regulatory capital on the originating banks’ balance sheets such that they can make further loans without breaching capital requirements. Large corporations can also issue their own ABS in order to finance activities. The underlying assets – e.g. mortgage loans, auto loans/leases, credit card receivables, etc. – generate steady flows of income for investors.

The green securitisation process:

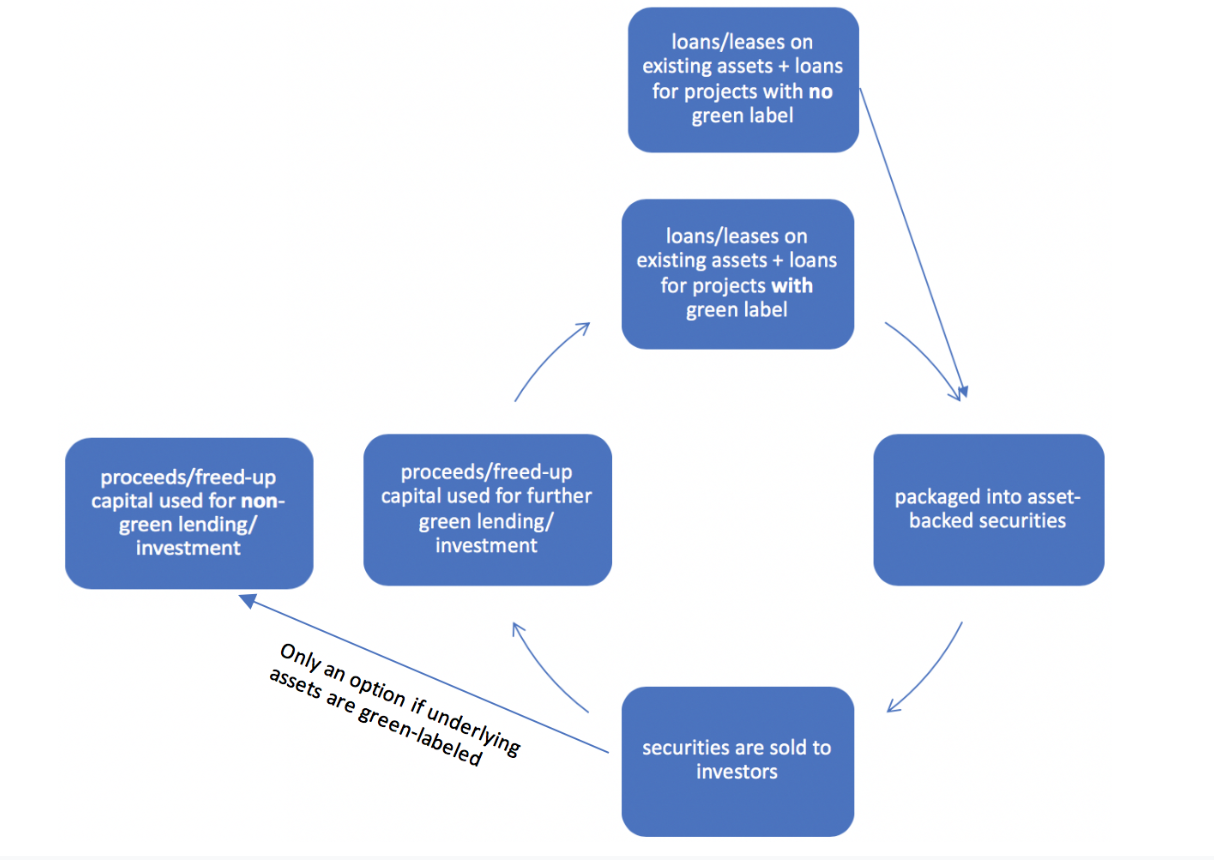

According to the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) – internationally considered a leading voice on green bonds – a security can be defined as green “when the underlying cash flows relate to low-carbon assets or where the proceeds from the deal are earmarked to invest in low-carbon assets.” While there now exists a variety of securities that fit this bill, each of which have different features, the basic process can be illustrated as follows:

Here is some further detail on the basic steps of the process illustrated above:

Loans and leases on existing assets are issued, and new projects are financed. Existing green-labeled assets include, for example, certified buildings, electric or hybrid cars, solar panels and wind turbines, while green-labeled projects are aimed at producing such assets or improving the energy efficiency of existing assets and production processes.

These loans and leases are packaged together into different types of green asset-backed securities (ABS), such as green auto ABS, green mortgage-backed securities (MBS), and green collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). As shown in the diagram, these securities can also be backed by non-green assets, including brown assets.

Securities are then sold to investors, who are currently signaling a high demand for green-labeled products, rapidly buying-up new offerings of green securities. Investors can trade the securities on the secondary market if they wish, but as of yet, they tend to hold on to any green products they can get.

The proceeds and/or freed-up capital (depending on the type of deal), is then used to finance other projects and assets. If the ABS is backed by green-labeled assets, the proceeds/freed-up capital can be used to finance non-green lending. If the ABS is backed by non-green labeled assets, then the proceeds/freed-up capital must be earmarked for green-labeled assets and projects.

The problems with green securitisation:

There are at least three big problems with green securitisation: (i) It allows for, and sometimes uses, the continued financing of high-carbon assets/projects, and does not necessarily result in new green lending/investment; (ii) it has the potential to increase systemic risk in the financial system; and (iii) the meaning of the ‘green’ label is far from settled.

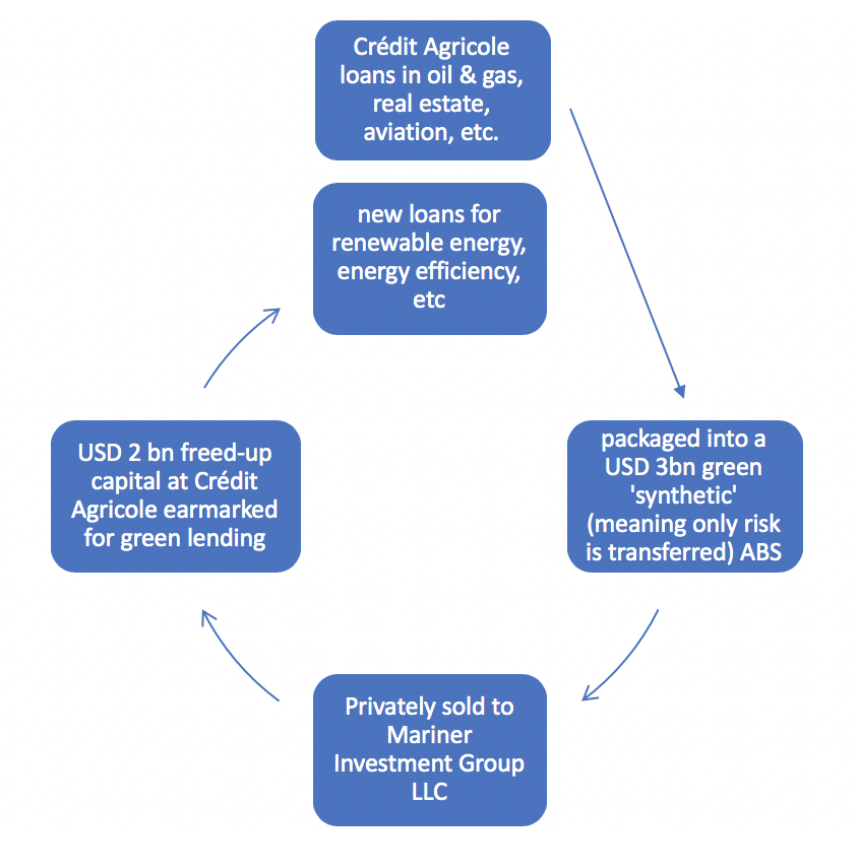

Crédit Agricole’s USD 3bn green synthetic ABS provides a good example of high-carbon assets/projects being used for green securitisation. The portfolio of loans backing this securitisation included oil/gas and aviation. Thus, while the freed-up capital from the deal was earmarked for green loans, it was enabled by the continued (rather than halted) financing of grey/brown assets and projects.

Similarly, Toyota Finance issued three green auto ABS amounting to USD 4.6bn backed by existing high-emission car leases, with the proceeds earmarked to finance new loans and leases on ‘low-emission’ vehicles.

Decarbonisation requires rapid divestment and decommissioning of high-carbon assets; keeping ‘brown’ assets alive and securitising them to raise funds or free up capital for new ‘green’ assets won’t cut it.

In other cases, as mentioned above, if the underlying pool of collateral backing the ABS is green-labeled, the proceeds/freed-up capital from the deal do not have to be earmarked for green lending/investment. So not only do these securities require no divestment, but they also do not result in any financing of new green assets or projects.

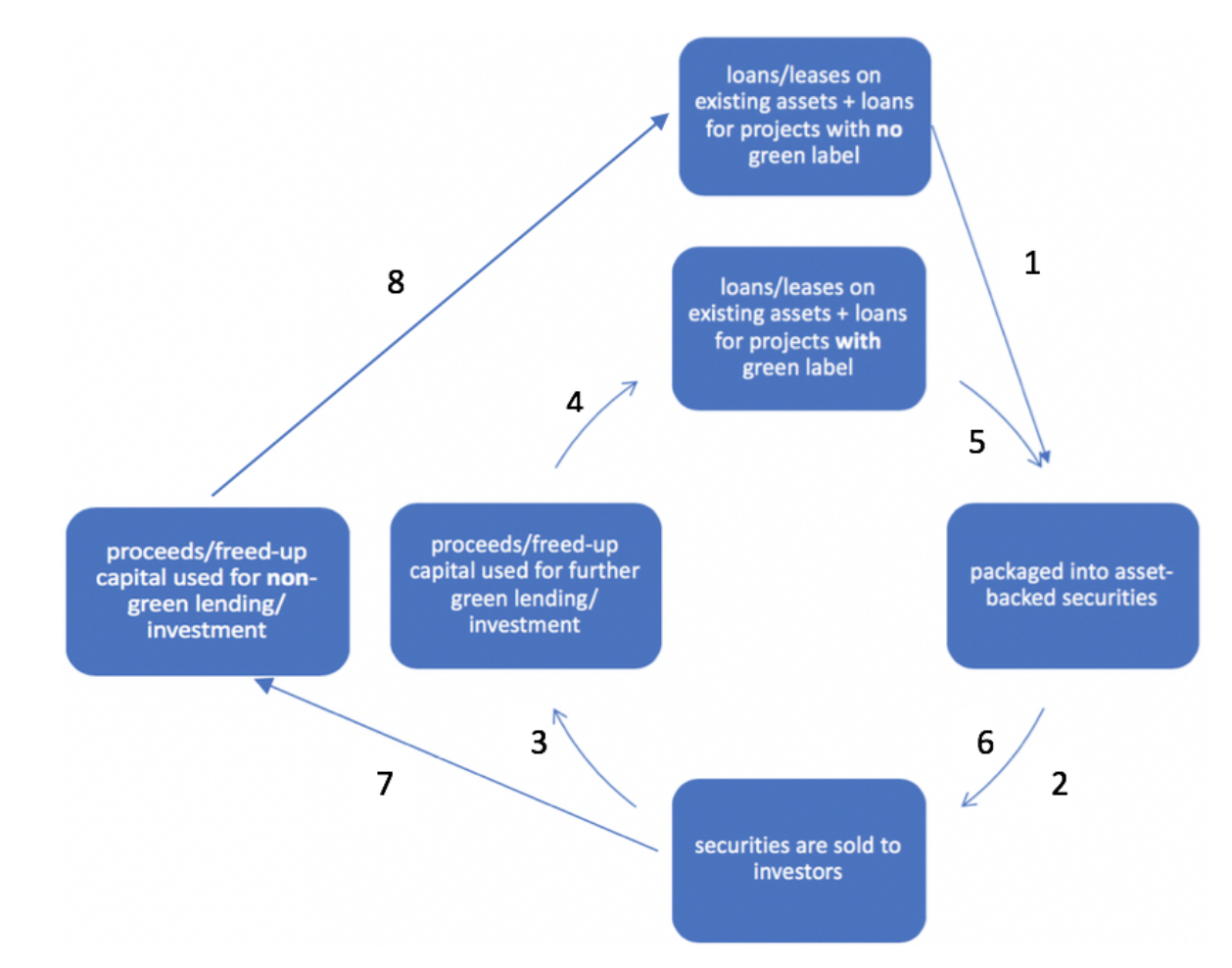

Even in the ‘best-case scenario’ where the process functions as a closed loop in which green assets/projects are used to finance further green assets and projects, still no divestment occurs. And in the ‘worst-case scenario’ illustrated below, already existing ‘non-green’ assets and projects can be used to finance new green ones, which could then potentially be used to finance new non-green ones!

The second problem applies to securitisation in general, not just of the green kind. The main purpose of securitisation is to evade capital requirements, which ultimately results in increased systemic risk in the financial system. While green securitisation alone is not sufficiently large-scale to pose any systemic risk, it is the fastest growing product in green finance. The OECD has estimated that issuance of green ABS for renewable energy, energy efficiency improvements, and low-emission vehicles could reach between USD 280-380 billion annually by 2035. Of more immediate concern, however, is that the ‘green’ label is being used to lobby for favourable regulatory treatment for certain highly regulated instruments, such as CLOs.

Lastly, there is the big difficulty of determining what assets and projects should be labeled as green in the first place (an issue that I discussed in a previous blog post). This should be an important focus for green finance activism, as bank lobbyists seek to water down standards that are already shaping up to be far too weak.

No role for securitisation in green finance:

Green securitisation provides no assistance in cutting off financial flows to high-carbon activities and does not necessarily result in new green lending. Rather, it assists the green PR efforts of financial institutions while doing little-to-no good for the environment. Moving forward, green finance activists must staunchly reject green securitisation.