Modern Monetary Theory and Positive Money, Part 2: Money and Debt (2)

This is the third in a series of blogs looking at the relationship between Modern Monetary Theory and the proposals made by Positive Money. It follows directly on from the second in the series.

Why does Positive Money refer to the money created under some of its proposals as ‘debt-free’? According to the principles of MMT, cash is a liability of the government. Therefore, ‘printing money’ (literally or figuratively) still results in monetary growth that is, technically speaking, matched by new ‘debt’.

Some, like Eric Lonergan, deny that the MMT definition of fiat money really covers the more important properties of debt. The aim of this blog series is to avoid pursuing that argument any further. Instead, there are some broad reasons Positive Money – among others – has continued to draw attention to debt and to emphasise the advantages of money creation by the central bank as opposed to the money created by private banks through making loans.

1) Homing in on private debt

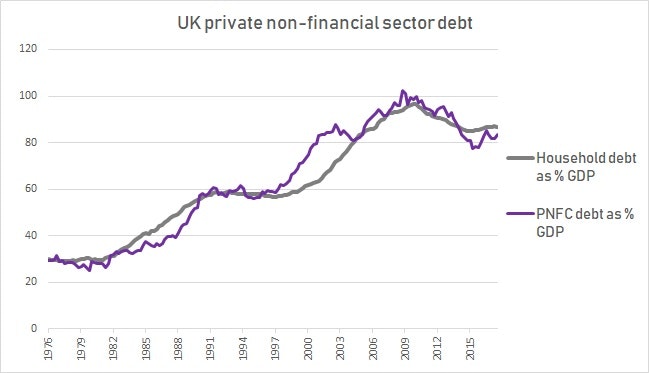

MMT scholars are determined to award a much more extensive role for government spending and to dispel the belief that public debt levels can ever be unsustainable. So in general, they devote less energy to talking about private debt compared to other heterodox scholars such as Steve Keen.

Randall Wray writes that ‘debt-free money cranks’ seem to prefer the government to print money rather than borrow it from banks, since doing the latter involves interest payments to the private financial sector. In his view, ‘cranks’ fail to understand the ‘operational realities’ of government balance sheets. On the contrary, avoiding talking about debt, for fear of perpetuating an ‘austerity narrative’, fails to offer a broader analysis of its impact on society.

There is a significant difference between money issued as debt by commercial banks, and money issued by the state, such as a central bank digital currency (CBDC). In the former, the private sector has increased liabilities. A CBDC, on the other hand, is a means of payment and source of income for the private sector that is created without the private sector increasing its net debt burden.

The only debt is on the part of the government. That debt is an obligation to release each bearer of money from their own obligation of payment (not itself a debt, but rather a legal requirement to pay, created by the public authority).

Again, publicly created money comes with no obligation for any private actor to repay. That is what makes it different from money created by banks. By spending money provided by the central bank into the real economy, the government can reduce the weight of debt bearing down on the private sector.

Source: Bank for International Settlements

The problems of private debt are several-fold. High levels of household debt or debt on the balance sheets of embattled firms threatens financial stability. The Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee has warned about ‘pockets’ of risk to the UK economy along these lines. Being deep in debt has a nasty effect on mental health – which the National Audit Office recently estimated will hit the public balance sheet with up to £250 million annually in increased costs.

Another important downside of private debt is that it perpetuates inequality. Positive Money does not seek to end debt, or even necessarily to end the payment of interest by government. Government bonds serve an important function as a stable supply of safe, low-interest assets that anchor market interest rates more broadly. However, a goal at the core of the Positive Money platform is to reduce the extraction of too much value from the rest of the economy by the financial sector (also known as ‘rent-seeking’ behaviour). Bank loans are one mechanism for the extraction of value.

Rohan Grey, founder of the Modern Money Network, summarised what’s at stake in this talk at the 2017 Democracy Convention. Private credit creation produces a pool of spending power in the economy that competes against the public purse:

“These different currencies are competing for the same basket of goods and services… Positive Money have identified that there is a tension between every new dollar that we allow a private credit system to create, versus a public system, in terms of their ability to lay claims on real resources [unless it produces more real goods and services than purchasing power].”

Private credit creation sees new money flow to activities that tend to enrich a small fraction of society and make life harder for everyone else. Interest compounds the problem. Money piles up in the financial industries while other sectors are starved of funding. The result is bad news for financial stability: artificial asset price inflation engenders volatility.

One proposal Positive Money supports to alleviate all these problems is a form of alternative monetary policy, or QE for people, which could be used to distribute an equal lump sum to each citizen. A household lifted from problem debt by a citizen’s dividend is likely to be unmoved by abstract claims that the government now owes them, to the tune of the money now in their current account. And language that makes sense to the beneficiaries of economic policy is important, as the next point shows.

2) Different communication strategies

To bring about change, the first task is to educate: about the nature of money and credit, but also about the consequences of the system we live with and why it needs fixing.

The previous post, which introduced the question of money and debt, referred to David Graeber’s historical analysis of money and how it is perceived by the community. Although we may be in a fiat money world with a monetary system dominated by bank credit, most people – public and policymakers alike – don’t appreciate or comprehend this reality.

MMT is one approach to the sort of education needed, one that might be described as taking a sledgehammer to the conventional view of the world. Education is first and foremost communication, and MMT writers have aimed to expand the arsenal of metaphors at their disposal to contest orthodox economics and policy. The second international MMT conference in New York City, (which Positive Money attended) displays the strength of the academic movement in working with campaigners and professional communicators, to bring abstract lessons to policy reality.

However, theirs is not the only approach. The communication tools preferred by Positive Money can be better understood as a pickaxe; chipping away at the old system rather than throwing the lot out the window.

Positive Money’s communication strategy combines an analysis of the problems currently associated with bank lending with the allure of an alternative form of finance provided by the public money circuit. The aim is to start where the audience is now, and lead them along the road to a better destination.

The debate over debt reveals this difference in strategy. By referring to bank deposits, Positive Money’s messaging establishes a clear link between people’s own money, their private debts, and the nature of the money supply. The public still broadly understands what private debt is – and most specifically interest payments to banks or other financial entities.

Where public debt is mentioned, care is taken to dismiss austerity as bad policy and bad economics. It is important to speak both these languages. Positive Money and its allies are well equipped to do so, as exhibited at a rally on the anniversary of the Lehman Brothers collapse. Speakers at the event skewered both fiscal austerity and the growing pile of private debt in Western economies.

Bill Mitchell – a leading MMT voice and the first to use an online blog to popularise MMT research – explains his dislike for political actors using language that doesn’t fit the MMT frame:

‘Those who think they are playing a politically savvy game by using neoliberal concepts to advocate progressive policy agendas just reinforce the neoliberal policy agenda.’

Is ‘debt-free money’ really undermining progressive economics everywhere, or is it winning new members of the public to the cause? Whose authority is it to decide when a concept becomes ‘neoliberal’? There is space for more than one interpretation. We’ll return to this notion of pluralism after one final point.

3) Money is also a means of payment

While it can help to think about money in terms of systems of debt, doing so exclusively would result in blind spots. In particular, Positive Money also seeks to draw attention to the power of the payments system, how it is designed, and how its ownership is currently concentrated in the hands of private interests.

We might imagine a metaphor for making payments in the modern economy as having to cross a bridge. Currently, a troll lives on the bridge and demands payment in return for a safe crossing. In the UK, that troll takes the form of VISA, Mastercard, or one of the big banks. However, the payments system is a natural monopoly and a crucial piece of public infrastructure, like the water and electricity networks. It then becomes clear that the system should be run in the public interest – public authorities should manage the bridge, to minimise or eliminate the need to buy off hungry trolls. This is part of the reason Positive Money campaigns for a central bank digital currency (CBDC), which would also involve the creation of a public payments system.

This is not the place to debate the design of the payments system. The point is that an insistence on seeing all money as debt can impede other, necessary conversations about how the form our money takes affects society.

Why pluralism is key

MMT champions the ‘zero-interest rate policy’ (ZIRP) and rejects the independence of central banks. Positive Money’s preference is first and foremost to amend central banks’ mandates and to equip them with the tools to carry out more direct policies – like monetary finance and credit guidance – in preparation for and in response to the next financial crisis. Yet objections to the ‘debt-free money’ term miss something: that its most practical function is to describe new policy proposals to a public not well-versed in abstract monetary theory.

The bottom line on many of these points is that the revolution in economic thought currently taking place must be a pluralist affair. Positive Money is on a journey from its inception as a relatively dogmatic framework for altering the monetary system to a much more pluralist approach. While this can be frustrating for those seeking all-inclusive answers, a pluralist movement has a much higher level of integrity and resilience to meet challenges that lie ahead. Hopefully, MMT thinkers will recognise the merits of pluralism. If not, the progressive movement will be the weaker for it.