The History and Future of QE: 3 ways the Bank of England’s analysis falls short

As Positive Money likes to point out, quantitative easing (QE) is a policy almost without historical precedent. With only scant and rather messy evidence to go on, the policy community is still uncovering many of its effects. Ben Broadbent, Deputy Governor for Monetary Policy, is the latest at the Bank of England to attempt to clear the waters. His observations on QE are illuminating, but have several shortcomings.

Mr Broadbent addressed ‘the history and future of QE’ in a speech to the Society of Professional Economists on Monday night. Paying credit to Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz for their seminal Monetary History of the United States, he drew a contrast between the policy failure of the Great Depression – denounced so completely by those authors – and the experience following the 2008 financial crisis. Unconventional monetary policy was certainly a radical break with the distant past.

Yet as the Bank of England approaches the ‘unwinding’ of QE (that is, starting to sell off the bonds it purchased using new reserves), the future looms large. The one lens we have with which to speculate about monetary tightening is the experience of easing over the past decade. In moving from history to future, the Deputy Governor’s analysis suffers from three core problems.

1) Too quick to dismiss the effects on asset prices

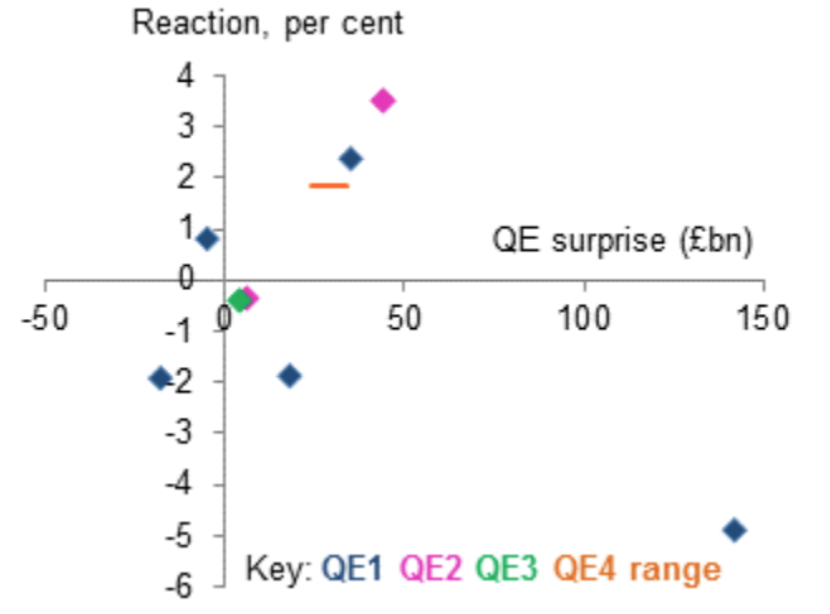

In the speech, Mr Broadbent argues that QE primarily supported the economy from collapse, rather than inflating or distorting it in certain sectors. In particular, he points to the prices of shares and houses, often said to have risen dramatically due to expansionary monetary policy. Chart 1 below, for instance, was presented as evidence suggesting that the effect on share prices is “harder to detect”.

Chart 1: The reaction of share prices to QE announcements has been mixed (source: Broadbent, 2018)

This analysis would stand up if it represented the long-run, sustained rise in the stock markets produced by an extended period of easy money. Unfortunately, Mr Broadbent chooses to examine the effect of QE announcements on share prices a few days later. His analysis therefore relies on a theory of markets that can fully price-in new information about policies when they are announced – in the context of an intervention which, by his own admission, is extremely novel and uncertain. Neither are short-term movements the relevant metric if we are interested, say, in the policy’s impact on the distribution of wealth over several years.

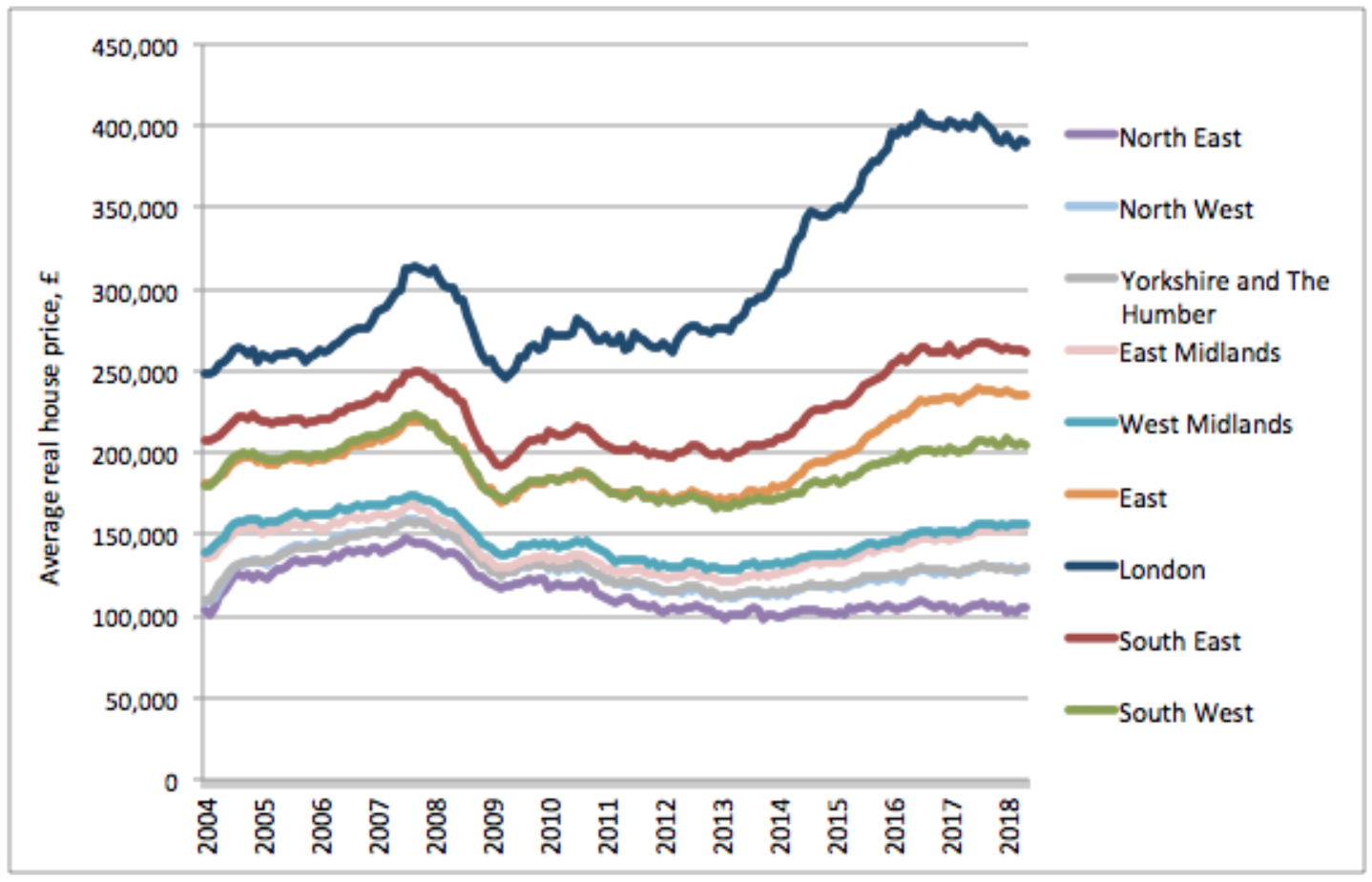

House prices are a second feature of Mr Broadbent’s argument. He quite reasonably looks to real figures – that is, adjusting for the general rise of prices across the economy – and observes that “the latest figure is barely any higher than it was in the middle of the last decade.” Chart 2 demonstrates this.

Chart 2: UK-wide, real house prices are only just returning to their pre-crisis level (source: Broadbent, 2018)

For a start, the effects of monetary easing vary geographically. Chart 3 replicates the analysis of real house prices, but for distinct regions of England.

Chart 3: Real house prices in London have risen by far more than in other regions (source: ONS and Positive Money calculations)

It is clear that in London, where the housing crisis is at its most severe, real house prices sailed clear of their pre-crisis levels almost four years ago. A massive gulf is opening between London and the rest of the country. It is likely that the financial wealth created by QE has, primarily, sloshed around the capital. Dismissing house price inflation on the back of nation-wide statistics is premature.

More generally, Positive Money has drawn attention to the reliance on rising asset prices as a source of significant weakness in the UK economy. Others, including at the Institute for Public Policy Research, have made extensive critiques along the same lines. The bottom line is that our economic model is unbalanced and unsustainable. This was as true before the financial crisis as it is today. It is therefore disingenuous, or at least unimaginative, to claim that conditions are rosy simply because house prices remain below their pre-crisis peak.

2) Over-confidence that ‘quantitative tightening’ will be manageable

The point on house prices reveals a second problem with Mr Broadbent’s account. As the MPC starts to consider unwinding QE, there may well be significant disinflationary effects. Here, Mr Broadbent suffers from a perplexing hubris. After spending much of the first half of his speech explaining how uncertain we are about the effects of QE, he seems relatively relaxed about what he calls ‘QT’ – quantitative tightening. His confidence can be seen in the MPC’s assessment that it can begin unwinding once the main policy interest rate reaches 1.5%, with the notion that the rate can be cut to support activity if QT provokes headwinds.

In the face of uncertainty caused by Brexit, and a global trade war potentially on the way thanks to Donald Trump’s efforts, room of 1.5 percentage points seems like awfully little for the MPC to be relying on. Given that Mr Broadbent wants QE to take credit for supporting house prices in the wake of the slump, we might want to ask what he foresees happening to the housing market when QE is reversed, just as Britain’s economic position looks particularly vulnerable.

In his speech, the Deputy Governor sees interest rates as offering a potential counterweight to QT – the Bank could tighten with one policy, and loosen with the other where needed. But given the scale of the uncertainty ahead, there is every possibility we could see ourselves back at the post-2008 arrangement, with both policies back on full blast to avoid a major downturn.

3) We need to talk about the counterfactual

The thought that a beleaguered MPC might, should things go wrong, turn once again to asset purchases leads to the final criticism for Mr Broadbent’s narrative: the absence of a counterfactual worth its salt.

It is understandable that Bank of England officials feel the need to defend QE from its critics. Over several years, monetary policy has been forced to prop up economic activity while the other hand of government, fiscal policy, withdraws support in almost every corner.

However, none of this means the Bank of England shouldn’t consider what might have been if it had taken alternative action. Assessing policy requires a reasonable counterfactual. The Bank’s chosen scenario against which to tally QE’s achievements is one where it adopted no expansionary measures at all. No surprise, then, that the Bank’s econometric studies find that QE was, on the whole, a good thing.

Our policymakers should broaden their horizons. The Bank could assess QE in light of a wider set of alternatives. In particular, it should consider more progressive forms of extraordinary monetary policy – what we at Positive Money group under the term ‘QE for People’.

One core proposal is for the central bank to credit the account of every citizen with a one-off payment. This policy, known as ‘helicopter money’, would surely have seen more wealth reach households and flow into the real economy than actually occurred under QE. It has gained support from such names as Ben Bernanke, former Chair of the US Federal Reserve, and – surprise – Milton Friedman, back in 1969.

Alternatively, QE for People might mean the Bank of England financing government expenditure, within clearly defined limits, for investment in crucial areas where unwinding QE might threaten stability – in building affordable homes, for instance. Such a policy would help jointly achieve the Bank’s dual targets of price and financial stability.

If leading Bank of England figures began to take the notion of new monetary policy tools more seriously, they might learn just how much is to be gained. As things stand, we are approaching quantitative tightening, Brexit, and another decade of severe economic imbalances without any new weapons in our central bank’s arsenal. Then, policymakers will have achieved something else unprecedented: failure to learn any lessons from a major crisis.