Inflation rises and living standards fall: how can the Bank of England respond?

Most recent figures suggest that consumer prices are increasing, while average wages are stagnating – meaning that people across the country are facing higher costs of living. To finance higher costs of living, more and more people are borrowing.

In the face of these conditions, how will the Bank of England respond?

Inflation at 2.3%

Latest inflation figures show that everyday consumer prices have increased by 2.3%. Consumer prices also rose in previous months, but they are much higher when compared to January’s rate of 1.8%, or the 0% price increases we were experiencing in 2015.

To an extent, consumer prices are increasing due to the fall in the pound after the Brexit vote, which has raised import prices (for more on this click here). Indeed, food prices in March were 1.2% higher than last year, the biggest annual rise in three years. However, fortunately, the ONS also said that a recent fall in fuel prices had helped to keep prices from rising further.

So how will the Bank of England respond to rising prices, many economists are asking what will the Bank of England do?

Household income and living standards

There are a number of variables that the Bank’s monetary policy committee will take into consideration when making decisions about the future course of monetary policy. One of the primary factors, no doubt, is household income. More specifically, household income in the context of three strong forces beckoning on the doors of our economy – higher consumer prices, stagnant wages, and consumer debt.

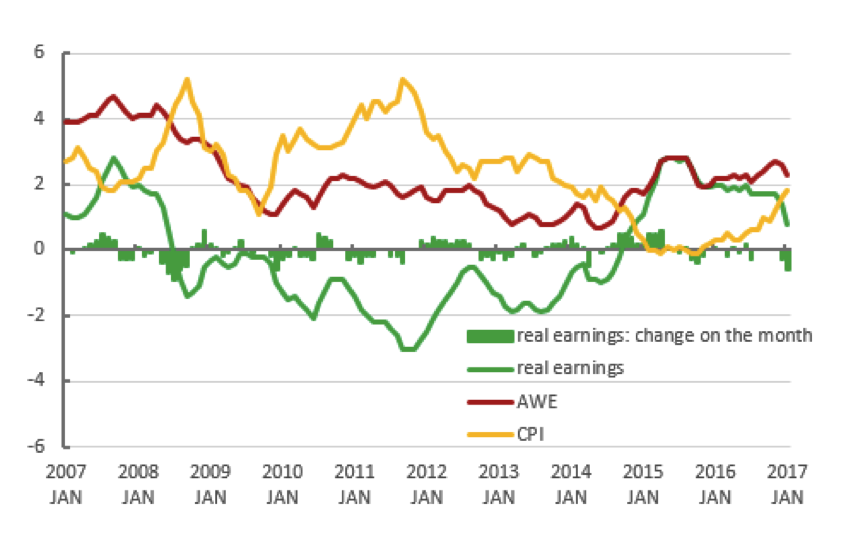

After the Global Financial Crash, from 2007-2014, consumer prices were growing faster than average wages. This means the purchasing power of wages had fallen, the average person could not buy as many goods and services with their wage. In economic jargon, the difference between wages and consumer prices is called real earnings (the green line in the graph below). Real earnings have largely been negative since 2008. Ultimately, this meant a higher cost of living all round and declining living standards for the average UK household.

Economic conditions changed from mid-2014-2016. Declining oil prices and depressed global growth led to a fall in consumer prices (the yellow line in the graph below). Consumer prices did not increase faster than average wages (despite subdued average wage growth, the red line). Meaning, people could buy more goods and services with the same wage. Therefore, for a short while, the cost of living in the UK was declining and the average UK household was better off.

Real Earnings Annual Growth, percent

(Source: TUC)

As we point out in the above, consumer prices are now increasing and despite all the talk about better-than-expected growth since the Brexit vote, this has not translated into higher wages. Wages are expected to remain stagnant in the future. The impact of these two forces on household incomes could be substantial. Rising prices and stagnant wages means the average household will not be able to buy the same amount of goods and services with their wage.

Higher costs of living and consumer debt

It is well-known that the fuel behind the better-than-expected growth in the aftermath of the Brexit vote – was household consumption. Household consumption has been driving economic growth for some time now. For the most part, household consumption has largely been financed by debt for some time now. For the most part, household consumption has largely been financed by:

1) Households dipping into their savings – savings are now at an all-time historic low.

2) Rising household debt, consumer debt is at its highest level since before the global financial crisis.

3) And more recently, by a short-lived increase in real earnings.

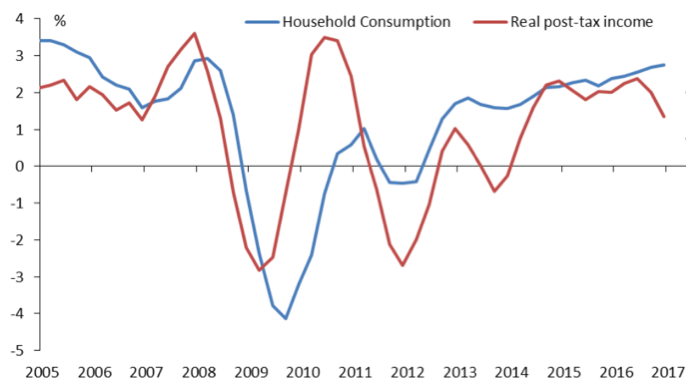

The problem, however, is that the recent growth in household consumption was not financed by growing real wages (the red line in the graph below). Therefore, it was financed in part by growing levels of consumer debt.

Household Consumption & Real Post-Tax Income

(Source: Bank of England)

Perhaps most worryingly, those on lowest incomes took on this debt, as research from the debt advice Stepchange Charity suggests:

“The average debt of our clients earning less than £30,000 increased by £569, to £12,897, in 2016. Over the same period, the average debt of clients earning more than £30,000 decreased by £2,160 to £29,340. Because those earning less make up a far higher proportion of our client base, this means that for the first time in eight years the overall average unsecured debt of our clients increased, from £13,900 to £14,251.”

As the TUC has shown, consumer borrowing as a proportion of household income rose sharply from 36.7% to 39.6% in 2016 – the highest figure since before 2008. The most recent statistics from the Bank of England suggest we are borrowing almost 10% more on credit cards today then we did only 12 months ago. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has calculated that household spent £34bn more than they earned in 2016, and could reach £50bn by 2021.

What could the Bank of England do? What should the Bank of England do?

Most economists, certainly those at the Bank of England, are expecting household consumption to slow down due to rising prices and stagnating wage growth – the higher costs of living. For example, Gertjan Vlieghe, External MPC member recently suggested:

“The consumer slowdown, which initially did not materialise, now appears to be underway. Given the hit to real income from a mix of subdued wage growth and rising inflation, I think the slowdown is more likely to intensify than fade away.”

In fact, retail sales indicators for 2017 suggest this may already be taking place. However, if household consumption continues on its current course, as it did in the second half of 2016, this will mean that it will have been driven by yet more household debt. If this continues, then it is a sign that monetary policy is too loose, and the Bank may have to consider tightening (for a concise explanation of how monetary policy works click here).

Of course, at the very extreme end tightening monetary policy too quickly could lead to a nasty reaction in the financial markets and potentially a stock market crash. However, simply raising rates will also mean higher debt servicing costs, which could have a massive detrimental impact on lower income households. Finally, if effective, it could depress spending and investment in a time of great economic uncertainty. Indeed, where is the spending that drives our economy going to come from if not from household consumption?

At Positive Money we believe the best course of action would be for the BoE to cooperate with the Treasury in order to finance a fiscal stimulus with newly created money (click here for an explanation of how such a programme could work). Indeed, as professor of macroeconomics Roger Farmer suggests, a fiscal stimulus financed by new money would give the Bank of England the option to stimulate spending whilst simultaneously tightening monetary policy if needed.