Money Creation & Interest: Is there enough money to pay off all the interest? (Part 2)

This is the second part of our article dealing with the argument that bank lending must lead to escalating debt because banks don’t create the money needed to pay the interest on the debt. Part 1 explained how the wrong conclusions have been drawn from the oft-repeated ‘banker on a desert island’ analogy. We showed that it is mathematically (and therefore logically) possible for both the principal and interest of a loan to be repaid.

Our primary point is that debt servicing problems through money shortages arise not from the exacting of interest per se. Instead, they are due to the failure to return money promptly to the economy debt free in the form of spending on goods and services. Whether it is a bank, business, or household, this problem arises no matter who is holding onto the money received. Further, it is of little importance, whether or not the money was received in the form of payments of interest or payments for goods and services provided.

In this second part we explore in more detail the technical factors contributing to this problem and a very rough estimate of how great an impact it has on private sector debt in the UK.

Real World Banking vs the Banker on a Desert Island

How great a problem is this in the real world? First, we need to compare the operation of the real banking system with Bob’s mythical bank (introduced in part 1). Bob makes loans by lending out coins, from his chest of gold coins. Banks make loans by increasing their deposit liabilities, as if from thin air. When Alice repays the principal of her loan, the money disappears back into the box and is lost to the economy. When a borrower repays a bank loan, the balance of the bank deposit decreases by the amount of the payment without increasing the balance of any other deposit. The money used to repay the loan is thus also lost to the economy.

Now when Alice borrows from Bob, she gains an asset, the gold coins that are hers to use as she likes. She also gains a liability, her obligation to repay Bob. When Bob lends to Alice, he loses an asset, the gold coins he has given her, but he gains a replacement asset in the form of Alice’s obligation to repay in future.

But in the real world banks don’t work like that. A borrower, like Alice, ends up with a new asset in the form of an increased account balance to match the repayment obligation incurred at the same time. However, the bank has not given up any asset, let alone cash, to match the loan asset received from the borrower. Instead, the bank has taken on an additional obligation in the form of a newly created deposit liability to the borrower to match the newly created loan asset received from the borrower.

So banks, unlike Bob, do not need money when they grant loans, and they do not necessarily need money when they are called on to make the payments for which the borrower wishes to use the loan. A deposit is not “money in the bank.” It doesn’t point to a sum of money that belongs to the depositor and can be reclaimed at any time.

But isn’t money destroyed when bank loans are repaid? What happens to the interest?

Banks process loan repayments by reducing the balance of the customers’ account, which is a liability of the bank, and simultaneously reducing its record of the debt outstanding, which is an asset of the bank. By reducing both sides of its balance sheet simultaneously, both the amount of debt and the amount of money fall by the same amount. So when loans are repaid, the bank effectively destroys money.

Payments of interest are handled slightly differently. As with a loan repayment, the balance of the customer’s account is reduced by the amount of the interest payment. But this time, no change is made to the assets of the bank. Instead, the bank’s liabilities fall, and consequently its equity (which is equal to the bank’s assets minus its liabilities) automatically increases. (Equity is a measure of what a bank or any firm would have left for shareholders if it sold all its assets and used the proceeds to pay off all its liabilities.)

(More technically, the accounting process is as follows. First, interest is debited from the customer’s account, reducing its balance, and credited to an accounting account called Interest Income, which records all the interest earned by the bank in the current accounting period. At the end of the accounting period, the Interest Income account is debited by the full amount of the account, and this amount is credited to Retained Earnings, boosting the bank’s shareholders’ equity.)

So the payment of interest results in money temporarily being ‘destroyed’, because the stock of bank deposits falls. However, in normal times, these deposits will be recreated when the bank makes its own interest payments to depositors, or payments to employees, suppliers, shareholders. A bank makes these payments by crediting the accounts of those entities, without making any change to its assets. This means that it makes payments by creating new money, increasing its liabilities and automatically reducing its equity. (Looked at another way, you could say that the bank is ‘re-creating’ the money it destroyed through interest payments.)

But does the above imply that banks can create infinite amounts of new money to pay employees and shareholders? The answer is no because these payments increase their liabilities whilst reducing their equity. This means that in the long-term their payments to depositors, employees, suppliers, and shareholders must be no more than the interest payments they’ve collected (and other income). Otherwise, they generate a loss, eat into their equity, and ultimately become insolvent.

Why do banks charge interest?

Banks are corporations with employees, suppliers, and shareholders, all of whom expect to be paid for their goods and services and receive dividends on their investment in the bank. Banks also have deposit holders, some of which expect to receive interest payments on the savings and other investment accounts they have bought from the banks. Banks, like all corporations, thus have substantial regular expenditures to cover.

For this reason banks, unlike Bob, require payments of interest as it accrues on a monthly or other regular basis. Except for very short-term or specialist loans, banks will not wait until loan repayment is due before collecting interest (remember that in the desert island analogy the principal and interest are due in one large sum). Thus, banks collect interest and spend that interest into circulation on a regular basis.

Interest is collected, in the main, to be spent. But not only interest. Banks, like lawyers, accountants, estate managers and architects provide numerous professional services to their account holders and other clients, for which they charge fees and commission. These charges, like interest, are paid out of the deposits of their clients and the economic impact and consequences of these payments are indistinguishable from the payment of interest.

With institutions other than banks, such as households and businesses, payments from customers and clients are credited to the deposits of those institutions. These are of course included amongst their assets. Such payments increase the value of their assets but leave their liabilities unchanged. This means that the net worth of the institution (the amount by which the value of their assets exceeds the value of their liabilities) has increased and this is reflected in an increase in the value of their shareholders’ equity.

The process is different for banks, but the effect is the same. Payments of interest and other charges received by banks do not increase their cash assets (their deposits at the central bank) but instead reduce their deposit liabilities to their borrowers and other clients. Their assets are left substantially unaffected but there is still an increase in the amount by which assets exceed liabilities so again their shareholders’ equity increases.

What about loan defaults?

All corporations have to report periodically to their shareholders the value of the assets they hold, the liabilities they owe to others and what is left over for the shareholders. If the value of their assets declines unexpectedly, this must be reflected in the reports. As the above analysis has shown, changes in the value of assets relative to liabilities trigger changes in the value of shareholders’ equity. Thus, whatever the institution, if the value of assets falls without a corresponding reduction in the value of liabilities, then shareholder equity takes the hit.

So a loan which has defaulted leaves the lending bank with an asset which is suddenly worthless, but the money created by the defaulted loan is still in circulation. Bank deposit liabilities have not reduced. Accordingly, the value of shareholder equity is reduced. This means that when bank loans default, banks have less scope for paying out dividends but, more importantly, the capital buffer supporting their remaining loans is eroded. This is because, whereas banks only need, say, £12 of equity to support a loan of £100 (see below), the default of a £100 loan reduces equity by £100.

Bank Capital and Money in Circulation

Banking regulations require that the level of capital (including shareholder equity) must be maintained above a defined fraction of the value of loans and other risky assets which the bank is holding. This can be achieved by retaining a greater proportion of their revenue from fees, charges and net interest receipts, which reduces the amount spent back into circulation. Alternatively, more shares or bonds can be issued and sold, which reduces the deposits of the purchasers and the amount of money in circulation.

Does this mean bank lending and new money creation is constrained by capital ratios? No, it may have implications for the profitability of banks – which is why so many of them oppose higher capital ratios – but there are a number of problems with reliance on capital ratios to limit lending as we explain here.

As banks increase their lending, they build up their equity, but by increasing their equity they reduce the amount of money in circulation. Does this mean that the desire of banks to increase the level of their lending itself generates an imperative for more borrowing to replace the money withdrawn from circulation?

Well, the available data sources are not up to the task of addressing that question head on. They can, however, give some assistance in answering the alternative question:- “assuming the withdrawal of money from circulation by banks when they increase their equity does indeed create an imperative for more borrowing, how great a contribution does that make to the problem of escalating debt?” But that is only part of the question. If withdrawal of money from circulation by banks when they build up their equity creates an imperative for more borrowing, then so would withdrawal from circulation due to hoarding by households and corporations.

Corporations and households hoard money primarily by allowing their bank deposit balances to accumulate by failing to spend back into circulation all that they have received in earnings and sales revenue from the deposits of others.

Calculating the Impact of Hoarding on Debt

The UK National Accounts show the sectoral balance sheets for households, financial and non-financial corporations and banks from which the holdings of cash and bank deposits by corporations and households can be extracted. Some of this money is held for transactions purposes and will be quickly spent back into the economy. Account needs to be taken of this in estimating how much of these balances represent hoarding.

For this purpose, we look at the National Accounts figures for total market output by financial and non-financial corporations and total household income for each year. We assume that this revenue is received in equal monthly instalments and spent back into the economy over the course of each month.

The average balance held for transactions purposes would then be half of the total monthly revenue for each sector. This amount is subtracted from the total money holdings for each sector to arrive at estimates for the amount of money hoarded by each sector.

Banks don’t hoard money in the form of bank deposits, but by increasing their equity, which is also shown in the UK National Accounts sectoral balance sheets.

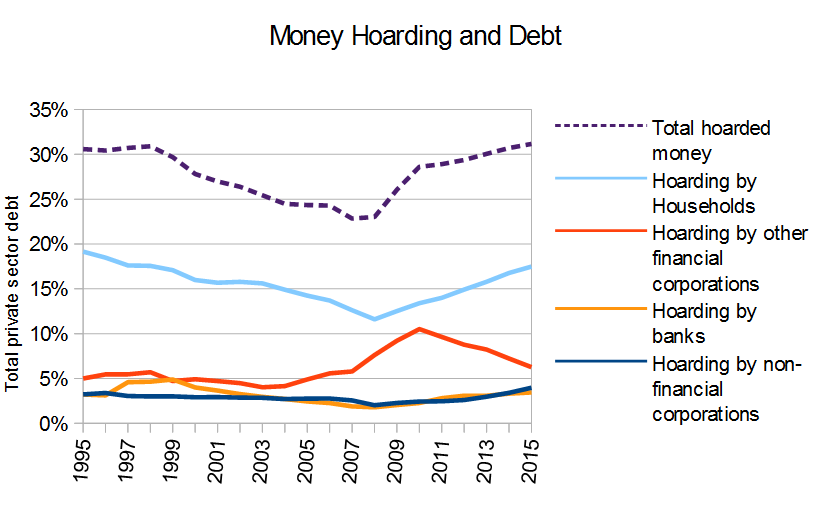

The chart below shows these estimates of hoarded money expressed as a percentage of private sector debt. This is the sum of the Bank of England’s estimate for M4L (total sterling lending by banks to the UK private sector), and the lending by non-banks represented by their holdings of debt-based securities issued by, and loans to, the UK private sector.

It should be noted that non-bank lending involves the transfer of money from the purchasers and lenders to the loan issuers and therefore does not involve hoarding.

Around 30% of private sector debt can thus be considered to be attributable to hoarding by households, corporations, and banks. In the current system, these hoards are all held on the balance sheets of the banks in the form of increased equity and inactive deposit liabilities. Where these generate an imperative for additional borrowing, the banks create new deposits, over and above those that are sitting idle. This creates the risk of instability if the holders of those idle deposit should unexpectedly decide to start spending again.

A Positive Money system will not directly reduce the need to borrow back into circulation the money withdrawn by hoarding. However, by requiring banks to draw only on the idle balances of their clients it will reduce systemic risk and the scope for rapid escalation of unsustainable debt. Sovereign Money Creation will also reduce the dependence on private sector debt to stimulate demand and spending in the economy.