Seven ways QE has not worked in the Eurozone

It’s been more than one year since the ECB’s Quantitative Easing programme started. Having pumped over €720 billion of central bank money into financial markets, in an attempt to boost Eurozone inflation, it is worth assessing whether QE is having its desired effect.

To achieve this end, we have written a formal evaluation of the Eurozone’s QE programme. To ensure the validity of our findings, we assess QE according to the ECBs own standards and the original theory within which QE was implemented.

It is within this context that our evaluation finds that ECB’s QE programme has predominantly failed to realise its intended objectives. Policymakers at the ECB need to begin considering better and more direct ways of increasing spending, such as QE for People.

Based on our preliminary evaluation, in this post we show the 7 key ways in which QE is failing to stimulate the type of economic recovery that the Eurozone needs. You may also find a video version of those findings below and the full assessment here (pdf).

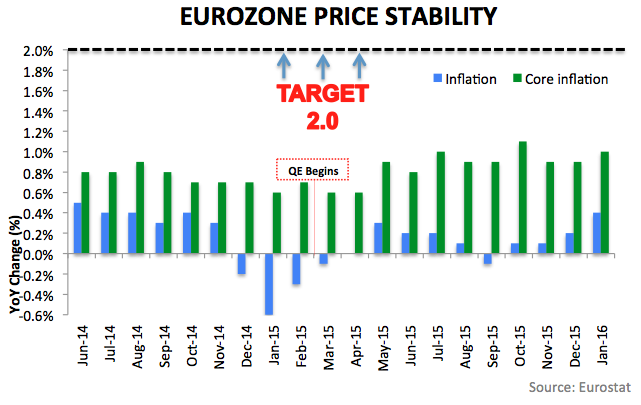

1. QE has not increased inflation

In the twelve months before the ECB launched its QE programme, inflation averaged 0.2% a month. Since launching its programme, inflation has more or less halved to 0.1% a month. Some might suggest this is due to oil prices. Yet core inflation, the measurement of prices that excludes items that face volatile movements in prices, such as oil, also suggests QE is not having its desired impact. Core inflation averaged 0.76% in the year before the QE programme began; and has averaged 0.87% since the programme was implemented.

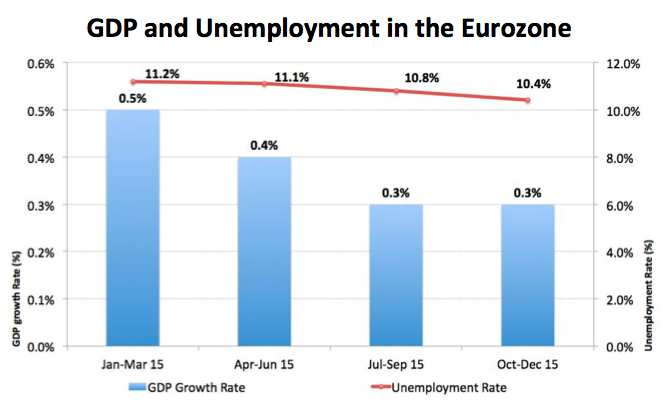

2. QE has not lifted the economy out of stagnation

While the primary objective of QE is to maintain price stability, this has to be considered in line with the broader (unstated) objective of Eurozone governments to facilitate growth and reduce unemployment. Since QE began, the Eurozone’s growth rate has actually contracted. In the three quarters proceeding QE, the economy grew by just 1%, whilst in the three quarters preceding QE the economy grew by 1.3%. Meanwhile, unemployment has dropped by 0.7% (primarily because of the consistent slow climb in growth starting in January 2014 and ending in March 2015).

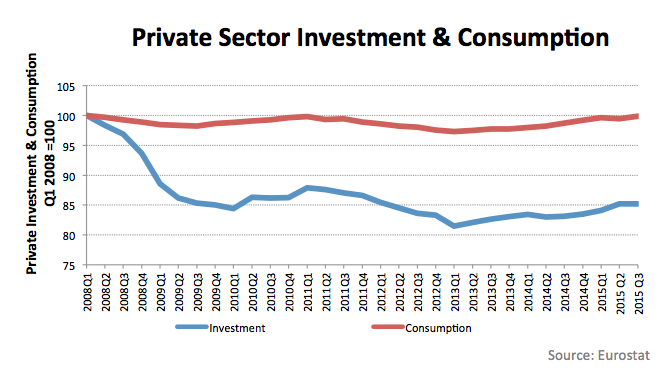

3. Consumption and investment remain low

By injecting new money into the financial markets, it is hoped that increased liquidity and lower borrowing costs will stimulate new lending for investment and consumption. Moreover, by artificially increasing asset prices, it is hoped that asset owners will consume more. However, pumping €720 billion of new central bank money into the financial markets has barely even influenced consumption and investment levels – and investment is still a far cry from what it was in 2008.

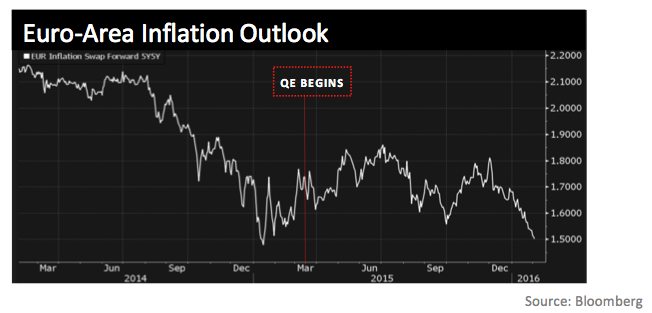

4. Inflation expectation is back to pre-QE level

According to the ECB, QE is meant to anchor expectations to a stable and positive inflation rate, which is vital to the Eurozone’s recovery. The ECB’s favourite indicator for inflation expectations is the ‘five-year, five-year’ forward swap rate. While inflation expectations experienced a rapid increase in the wake of the announcement of QE, short and medium term expectations are now back where they were in late 2014.

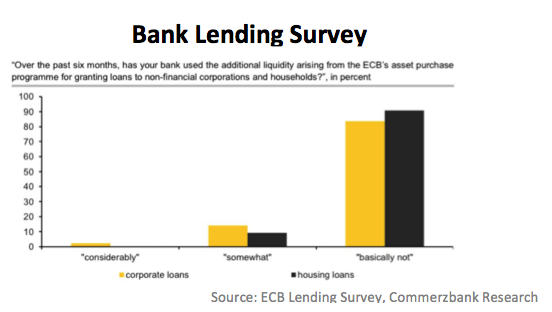

5. Better lending conditions haven’t translated into more lending

Injecting new central bank reserves (liquidity) into the banking system, relieves banks’ balance sheet constraints and lowers the funding costs of banks. This should allow banks to increase their lending to the economy. Looking at lending for spending in the real economy, last month consumer lending increased by 1.4% and business lending declined by 0.55%. The ECB will suggest that credit conditions are better and demand is increasing, but the fact remains that real economy lending remains flat – and is still well below what would be needed to trigger a significant increase in spending.

6. No significant increase in exports

By artificially influencing financial yields and interest rates, QE devalues the currency, which is intended to lead to an increase in exports. This channel had its greatest effect when QE was first announced – and has since faded. According to the trade weighted Euro index, the NEER, the euro has a higher exchange rate than before QE started. It is hardly surprising therefore that between September 2014 and 2015, the Eurozone managed to increase its net exports by a mere €3 billion.

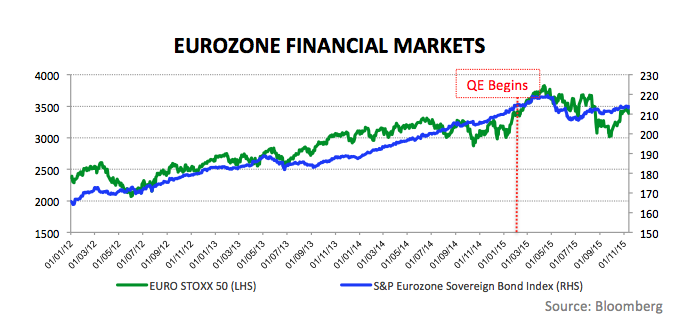

7. Portfolio rebalancing hasn’t benefitted productive investment

By increasing asset prices, QE is intended to reduce long-term yields of safe assets – prompting investors to rebalance their portfolios in search of higher yielding risky assets. There is evidence that the announcement of a QE programme most likely had a slight portfolio-rebalancing effect. However, this effect was short-lived and has since faded away. Indeed, yields have been falling since 2012 but we did not see an increase in investment or bank lending, due to portfolio rebalancing back then. This begs the question as to why we should expect to see one now.

Conclusion

At the very best QE is generating sluggish results. The ECB will argue that had it not been for its QE programme, the economy of the Eurozone would be worse off. However, it is important to note that the objective of QE for the Eurozone was never to prevent the Eurozone’s economy from falling further into a recession. Moreover, it is impossible to prove (or disprove) that the Eurozone economy would be worse off had it not been for QE. One could argue that the grounds for implementing policy programmes worth trillions of Euros cannot come down to such counterfactual arguments.

It is within this context that this paper finds that ECB’s QE programme has predominantly failed to generate its intended results. Policymakers at the ECB need to begin considering better and more direct ways of increasing spending, such as QE for People.

This article was published originally on the QE4people.eu website