Mervyn King’s “Pawnbroker for All Seasons” Explained

Lord Mervyn King, who was Governor of the Bank of England from 2003-2013 and saw the financial crisis play out from the centre of the action, has just released his new book, The End of Alchemy. Our short review of the book is available here. This article explains his proposal for the Bank of England to become a “Pawnbroker for All Seasons”.

The proposal does not ultimately stop banks creating money. Instead, it ensures that banks can always repay all their short-term depositors on demand, with the help of the Bank of England.

If used in a certain way, it could give the Bank of England better tools to regulate the degree of money creation by the banking system, and could even be used as a transition to a banking system where banks are unable to create money. But, as we’ll explain below, in its current form it still leaves the power to create money in the hands of banks and is unlikely to prevent them financing large debt-fuelled bubbles in housing, amongst other problems.

The Pawnbroker for All Seasons

The key requirement of King’s proposal is that every bank must always be able to repay all its deposits that are less than 12 months in maturity (all current accounts – demand deposits – and short-term savings accounts).

To help the banks be able to do this, the Bank of England would offer a line of credit so that the bank could borrow from the Bank of England, at a price, if customers needed to withdraw more than the bank had in liquid funds. Rather than being a “Lender of last resort” who lends to banks only when they are facing a bank run or liquidity crisis, King wants the Bank of England to become a “Pawnbroker for all Seasons”, which would commit it to lend to banks at any point in time, regardless of the circumstances.

Here’s how the proposal would work in technical terms. I’ll try to explain the banking jargon as we go:

The central bank stands willing to lend at any time against collateral of any quality at an appropriate ‘haircut’.

‘Collateral’ refers to a financial asset, such as a bond or mortgage, that can be used as security in case the borrower (the bank) is unable to repay.

A ‘haircut’ means that if the collateral is worth £100, the central bank may only be willing to lend £90 – a haircut of 10%. This haircut ensures that if the borrower is unable to repay, there is more than enough collateral to cover the losses even if the value of the collateral goes down.

The central bank would ‘lend’ against this collateral by creating new central bank money.

The haircut could range from close to 0% up to 100%.

A haircut of 0% would be very rare as it would only apply to a completely risk-free asset.

A haircut of 100% would be the same as saying that the collateral is worthless and not acceptable to the central bank.

Well in advance of a crisis, banks would have to ‘pre-position’ their collateral with the central bank. This means that the central bank could inspect the collateral to assess its quality and decide on the appropriate haircut that it would apply if the bank ever wished to borrow against that collateral.

Collateral that is prepositioned with the central bank could not be used as collateral for other borrowing by the bank, so there would be an opportunity cost to making use of this borrowing facility.

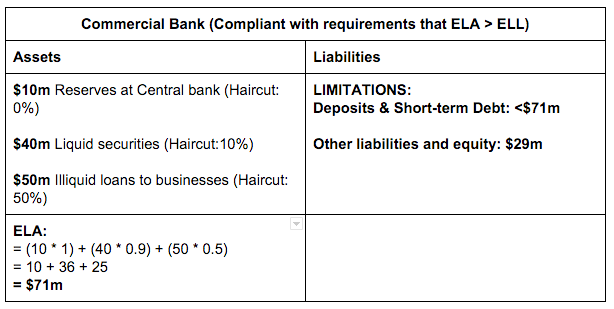

The total pre-positioned assets, reduced by the respective haircuts, would make up the Effective Liquid Assets (ELA) of the bank. This shows the total amount of central bank money the bank would be able to access at any point in time.

The ELA includes existing reserves held by the bank in its account at the central bank. The haircut on these is 0%, naturally.

The bank’s Effective Liquid Liabilities (ELL) is made up of:

Total Demand Deposits

Short-term Unsecured Debt (up to one year in maturity).

The key regulatory requirement on banks (as well as on financial intermediaries) would be that Effective Liquid Assets must be greater than Effective Liquid Liabilities, or in shorthand, ELA > ELL.

The book provides a worked example. The bank below prepositions all of its assets. (In practice, banks would only want to preposition a portion of their assets). Although the assets in total make up $100m, once the haircuts have been applied, the total Effective Liquid Assets are $71m. This means that, in the event of a bank run, it could first pay out its $10m of funds at the central bank, and then use the Pawnbroker facility to access a further $61m of funds.

In order to meet the requirement that Effective Liquid Assets must be greater than (or equal to) Effective Liquid Liabilities, the bank must issue no more than $71m of demand deposits and short-term (<12 month) debt.

How to Transition to the Pawnbroker For All Seasons

If the Pawnbroker scheme were to be implemented, the first step would be for each bank to calculate how far they are away from meeting the “No Alchemy rule”: the requirement that ELA > ELL.

For instance, if the bank above had $90m of demand deposits and savings accounts of less than 12 months maturity, and only $10m of longer-term funding and equity, then the “degree of alchemy” is:

(ELL – ELA) / Balance Sheet Size = Amount of alchemy

($85 – $71) / $100 = $14 / $100 = 14%

Each bank would have a number of years to get the degree of alchemy down to zero, so that ELA > ELL. (In practice the degree of alchemy at most banks would be significantly higher than the 14% given above.)

Where the Proposal is Useful

King highlights the fact that in a panic, everyone ultimately wants to hold the safest form of money, which is the money created by the central bank. He sees the role of the central bank being to create sufficient money to meet this demand:

“Experience has demonstrated the importance of a public body – normally the central bank – responsible for two key aspects of the management of money in a capitalist economy. The first is to ensure that in good times the amount of money grows at a rate sufficient to maintain broad stability of the value of money, and the second is to ensure that in bad times, the amount of money grows at a rate sufficient to provide the liquidity – a reserve of future purchasing power – required to meet unpredictable swings in demand for it by the private sector.” (p163)

Consequently, when there’s a panic, there will be runs on all kinds of financial institutions. Only the central bank is able to create truly risk-free money to stop these runs. The Pawnbroker facility allows the central bank to meet this shifting demand for money.

This is a useful tool. In a sovereign money system (where banks cannot create money) such a facility could be used to put more money into the economy when there is a panic and people want to switch out of holding risky assets. Such a facility would be an alternative to freezing Investment Accounts when requests for redemptions became too high. We’ll write more about this later.

However, the proposal (by design) does not stop banks creating money, as we’ll explain below. It may make the system safer, but there is still the potential to allow banks to generate debt-fuelled bubbles.

How Banks Could Create Money under the ‘Pawnbroker For All Seasons’

The haircuts set by the central bank would determine the extent to which banks could finance their loans by issuing new money (in the form of deposits). Ultimately the level of the haircuts would determine how the bank must split its short-term (<12 month) and long-term funding.

Here’s how the proposal would allow the banking sector to continue creating money, as a whole:

Imagine the banks issue an extra £10bn of mortgages to relatively low risk borrowers.

The banks issue £10bn of new deposits (new money) which the borrowers use to buy houses.

However, now the banking sector as a whole is in breach of the requirement that ELA > ELL, because (ELA $9bn < $100k ELL).

The banks preposition the mortgages as collateral with the ‘Pawnbroker’ facility. The Bank of England imposes a 10% haircut on this collateral.

Consequently, the mortgage assets have a face value of £10bn, with an Effective Liquid Asset value of £9bn.

To meet the ELA>ELL requirement, the banks must convince the holders of £1bn of deposits to convert their deposits into long-term funding (>12 months).

Now ELA is £9bn and ELL is also £9bn. So the banking sector is no longer in breach of the ELA>ELL rule.

Consequently, in this model the banks have collectively been able to issue an additional £10bn of mortgages by creating £9bn of new deposits. This process can be repeated as many times as necessary. This means it is entirely possible to have the same kind of housing boom financed by newly created deposits under the Pawnbroker system.

The only way to guard against this is to increase the haircuts on certain assets whenever the central bank feels a bubble may be developing. This would reduce the amount by which banks can finance their lending by creating new money; if the haircut in the example above was 50%, then banks would have needed to convert £5bn of deposits into long-term funding, rather than £1bn. This is a much bigger challenge. Since long-term funding is more expensive than short-term funding (i.e. banks have to pay more interest on 2 year savings accounts than on current accounts), this raises the cost to the bank of lending, and will encourage them to lend less. But King suggests that the haircuts would be changed very infrequently: they are not intended to be a tool to be adjusted frequently to manage bank lending.

Conclusion

Mervyn King’s proposal does ensure that banks will be able to handle bank runs without a problem. But it does this by saying that if people want to shift from risky bank deposits into central bank money (i.e. if there’s a bank run), the central bank will create that money on demand. This is in contrast to the Positive Money proposal of simply allowing people to hold risk-free central bank money at the central bank in the first place, and preventing banks from creating money, full stop.

The Pawnbroker proposal could be used to gradually reduce the capacity of banks to create money, if the haircuts on collateral at the Pawnbroker facility were significantly increased over time. But as the proposal stands at the moment, it’s hard to see how it addresses problems other than bank runs. The effect of the proposal is to require banks to hold slightly more longer-term funding, which slightly raises the overall cost of their funding. But banks in this system would still have their ability to create money, and could still finance a property bubble by creating money.

King argues that the Pawnbroker For All Seasons approach would force banks to pay a ‘price’ for being able to issue money. But it’s not clear yet that the price they’d pay would be high enough.