How much debt is too much? When should the Bank of England create new money to finance spending?

How much debt is too much? When should the Treasury borrow money and when should the Bank of England create new money to finance spending?

Total UK household debt is exceptionally high and projected to increase even further. Meanwhile, government debt is also at an all time high. Concerns over these circumstances have prompted Professor Robert Skidelsky of Warwick University to ask, ‘How much debt is too much?’

In this post, we highlight the pertinent points that Professor Skidelsky makes about debt. We then clarify our position on when the Treasury could borrow money to finance spending and when the Bank of England should create money to finance spending.

Debt to GDP ratio

Firstly, debt in itself is not a bad thing, in fact it can be a very good thing! So it’s important to mention that the sheer volume of debt is not as much of an issue as the ability to pay that debt back. This is why economists prefer gauging levels of debt by comparing the ratio of debt to income – as this gives a better indication of whether the debt can be repaid or not.

Accordingly, Professor Skidelsky sets out to answer the question: ‘Is there a “safe” debt/income ratio for households or debt/GDP ratio for governments?’ His conclusion is that “In both cases, the answer is yes”. However, “…in both cases, it is impossible to say exactly what that ratio is.”

Household Debt

More specifically, Professor Skidelsky suggests that the answer to this question ultimately depends on the circumstances. The case studies of household debt in Denmark and the USA are first used to illustrate this point:

“Consider Denmark and the United States. In 2007, Denmark’s household debt/income ratio reached 269%, while the US peak was 125%. But household default rates have been negligible in Denmark, unlike in the US, where, in the depths of the recession, almost a quarter of mortgages were ‘under water’ and some homeowners chose strategic default – fueling further downward pressure on housing prices and harming other indebted households.”

The difference between household debt in these two countries, argues Skidelsky, is the composition of borrowers:

“In Denmark, high-income households borrowed the most, relative to their income, and standards for mortgage lending remained high (mortgages were capped at 80% of the value of the property).

In the US, households with the lowest income (the bottom quintile) had a higher debt/income ratio than the top 10%, and mortgages were dispensed like gumballs. In the US, as well as in Spain and Ireland, banks and households became what the Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf called “highly leveraged speculators in a fixed asset.”

Government Debt

Next, Professor Skidelsky shows that the appropriate debt to GDP ratios for governments also depends on the circumstances:

“As for government debt, Japan’s debt/GDP ratio is 230%, compared to Greece’s 177%. But the consequences have been much more dire in Greece than in Japan. The distribution of the creditors is crucial. Most of Japan’s bondholders are nationals (if not the central bank) and have an interest in political stability. Most Greek bondholders are foreign banks. Yet, while crises of confidence come much sooner if debt is mainly owned by foreigners, no steps have been taken to restrict government borrowing to domestic sources.”

In accordance with what Positive Money has argued for some time now, the reduction of government spending without a corresponding increase in exports, will ultimately mean that growth will depend on the private sector having to borrow more:

“And, while governments have been trying (albeit ineffectually) to reduce their net liabilities, they have been encouraging households to increase their debt, in order to support the restoration of “healthy” growth.”

How Debt is Used Matters

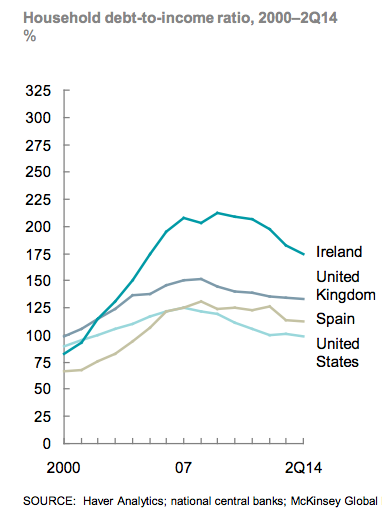

A report by McKinsey shows that since 2007 government debt globally increased by $25 trillion. Government debt-to-GDP ratios are forecast to rise in all advanced countries except for Germany, Ireland, and Greece.

This might seem alarming to some, not so much because government debt is increasing, but because it further illustrates the reality that growth everywhere in the world is dependent on debt.

We do need to be cautious about how we approach debt and not stigmatize it. Attention should be paid to where and how debt is being used. As we have suggested before, when new debt is used to finance activities in the financial markets (i.e. to buy pre-existing assets) then there will be very low increases in output and therefore people’s incomes. However, if debt is to finance activities in the real economy then output will increase and so will people’s incomes.

This is why Professor Skidelsky suggests that we have to pay attention to how debt is used:

“But a great deal of the alarm is based on the oft-repeated canard that government spending is unproductive and a burden on future generations. In fact, future generations will benefit more than the current one from government infrastructure investment”

Issue Debt or Create New Money?

Professor Skidelsky then suggests that the government is in a great position to borrow:

“But now, when real interest rates are almost zero or negative, is the ideal time for governments to borrow for capital spending. Bondholders shouldn’t worry about debt if it gives rise to a productive asset.”

With very low interest rates, there is an argument that now is a great time for the government to borrow. At Positive Money, our position is that the government can borrow money (but doesn’t have to) from the financial markets if it wants to fund new capital investment projects.

However, we also believe that if indicators suggest that there is spare capacity in the economy, that aggregate demand is below a certain threshold – to the extent that price stability is endangered – then the Bank of England should step in. It should proactively create new money to finance government expenditure up until indicators for aggregate demand reach the desired threshold.

Thus, while interest rates are low and the government can benefit from low borrowing costs, with the UK in disinflation territory and aggregate demand not at its desired level (despite cheap oil prices and increasing real wages) the Bank of England should be creating money to finance expenditure. This is why we suggest using Sovereign Money Creation to stimulate the economy.