Digital Cash & Your Privacy

Since we released our paper Digital Cash, which proposes that members of the public should be able to hold an electronic version of notes and coins in accounts at the Bank of England, a number of people have raised concerns about the privacy implications.

The more sensible concerns focus on the risk of one institution – the Bank of England, Federal Reserve or European Central Bank, for instance – having access to everyone’s account balance and spending records.

Some of the more alarmist comments, such as this bizarre article by Geoffrey Gardiner, propose a dystopian future in which accounts at the central bank are used as a tool of mass surveillance:

“The system of transaction accounts at the central bank will be used to keep track of the population. Every person will be allocated an account at birth and vital details will be recorded and updated. The records will include a record of the person’s genome. The bank will issue identity documents. The transaction account number will be the person’s identity and passport number, and also the number of his or her tax account. Transaction account statements will be sent automatically to the tax office, which will have the duty to debit it with all assessed taxes. Every immigrant or visitor to the country will get an account and give similar identity details.”

Granted, the tax authorities might quite like the idea of seeing all the money that flows into and out of your bank account. Presumably, so would the Serious Fraud Office. Advertisers would love the opportunity to purchase your name, address and monthly expenditure; the government already sells the data on the voter register unless you opt out when registering, so it’s plausible that they would be open to selling transactions data if you forget to opt out.

It’s impossible to know if or how this data could be abused or misused in the future, so let’s agree that holding everyone’s transaction history at one institution is too much centralisation of data and open to abuse. How can we avoid this?

The answer is remarkably simple. The technology infrastructure that would run digital accounts can be designed to ensure that the Bank of England (or your own country’s central bank) would have no idea who you are, or who you’re making payments to. All they would do is provide an electronic account to store your digital cash.

How Digital Cash Would Work

First, let’s recap how a system of digital cash accounts would work, according to the Indirect Access proposal in Digital Cash: Why Central Banks Should Start Issuing Electronic Money:

From the paper:

Option 2: Indirect Access via Digital Cash Accounts (DCAs)

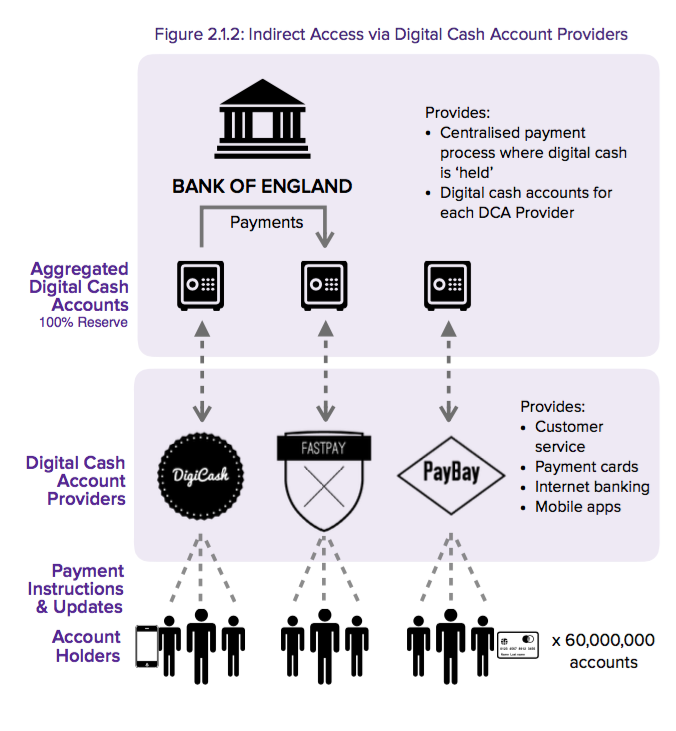

In this Indirect Access approach, the Bank of England would still create and hold the digital cash, but all payment and customer services would be provided by (or ‘administered’ by) private sector firms.

The model for this is outlined in detail in our paper Increasing Competition in Payment Services (Dyson & Hodgson, 2014). In this model, banks or technology companies (such as smartphone app developers) would provide a special type of account, which we will call “Digital Cash Accounts” (DCAs) throughout this paper. The firms providing these accounts will be referred to as “DCA Providers”.

The DCA Provider would have responsibility for providing account statements, payment cards, balance checks, sort codes, account numbers, internet and/or mobile banking, and customer support by phone or email. They would also be responsible for allowing the DCA holders to make payments via the normal payment networks – BACS, FasterPayments, Visa, MasterCard etc. This would enable DCA holders to spend digital cash in the same way that they can spend bank deposits.

Any funds paid into the DCA would be held electronically in full (i.e. 100% reserve) at the Bank of England18 (Figure 2.1.2). This means that the DCA Provider would always be “fully liquid”: it could repay all its customers the full balance of their account at all times. This is in contrast to conventional banks, which can only ever repay a fraction of their depositors at any point in time.

Crucially, the digital cash held in a DCA would legally belong to the account holder, not the DCA Provider. The digital cash would be held in a separate client account19 at the Bank of England, and so would not be held on the balance sheet of the DCA Provider. The DCA Provider would ‘administer’ the digital cash, but would never own it.

Separating the Data

There are three main parts of the data that would be recorded in a digital cash payment system:

The Customer Data – Stores the personal and contact details of customers

The Accounts Data – Stores the money (digital cash)

The Transactions Data – Stores the history of transactions: how much money was transferred from one account to another.

The Customer Data

The customer data is simply a record of the customers. Each Digital Cash Account Provider would have a database of its customers. It would look something like the following:

FastPay Customer Records

NameAddressContact DetailsSecurity DetailsDigital Cash Account IdLouis Armstrong51 Regents Way01234 567890************10251610……………

DigiCash Customer Records

NameAddressContact DetailsSecurity DetailsDigital Cash Account IdElla Fitzgerald23 Court Lane01530 123456************50361922……………

This data would be held by the Digital Cash Account (DCA) Provider, NOT by the Bank of England. The DCA Provider needs this data to know who owns the money in an account and ensure that only that person can authorise payments from that account. They’re required to gather this data by anti-money laundering regulations, so there’s no way (currently or with digital cash) that you can get an anonymous account in the way that you can get an anonymous pay-as-you-go phone. But so long as the DCA Provider is keeping up with its responsibility to screen account applicants according to Anti-Money Laundering requirements, the Bank of England doesn’t need to know the personal details of the account holder. In fact, it would prefer not to have the responsibility for storing all that data and keeping it up to date.

The Digital Cash Account Data

The Bank of England needs to hold a record of each Digital Cash Account, which would record the account’s balance. (Digital cash is ultimately just a number in the computer system of the central bank; the number you see when you check the balance is the digital cash.) The data would look something like this:

DCA Provider IdAccount IdCurrent BalanceFastPay 08-32-2210251610£1000.00DigiCash 09-21-2250361922£0.00FastPay 08-32-2212988253£50.00

Because Digital Cash is a liability of the Bank of England, it must be stored in the Bank of England’s computer systems. There’s nowhere else for it to exist – it’s not a paper or metal token that can be physically carried around. (One exception to this is a central bank-issued cryptocurrency on a distributed ledger system, but we’re a few years away from that kind of technology being usable to run a national payment system.)

You’ll notice that the account data is anonymous; the Bank of England doesn’t know who owns the £1000 in account 10251610. It does know that a customer of FastPay owns that account, but it would have no legal authority to ask FastPay to reveal the details of its customers. So the Bank of England wouldn’t know what transactions you’ve been making (and quite frankly, I doubt they would care).

In the example above, Louis’s Digital Cash Account (DCA) Provider (FastPay) would be able to check the balance of Louis’s Digital Cash Account at the Bank of England. So Louis and the DCA Provider know his balance, whilst the Bank of England knows there’s an account with that balance, administered by FastPay, but doesn’t know to whom it belongs.

The Transactions Data

Finally, there’s the transaction data: the payments that were made from each account, and to which account each of those payments was made.

If Louis Armstrong (whose Digital Cash Account Provider is FastPay) wants to pay £250 to Ella Fitzgerald for rent, he’d log into internet banking (or a mobile phone app) and set up a payment. Behind the scenes, the payment instruction that would be sent to the Bank of England’s payment processor would look something like the following:

Sender Account IDReceiver AccountAmountDate & TimeMessage & Reference08-32-22-1025161009-21-22-50361922£250.002016-05-29“Rent for March, from Louis Armstrong to Ella Fitzgerald”

The Transactions Data is simply a record of all these payment instructions.

Again, the Bank of England doesn’t know the identities of the parties that this payment is between; it simply knows that a payment has gone between these two numbered accounts.

Of course, one obvious privacy issue appears in the “Message and Reference” in the table above. The receiver of the payment needs to know who that payment is from, and since the Bank of England doesn’t know who the payer account belongs to, that information must be sent along with the payment instruction by the Digital Cash Account Provider. But this message reveals who the payment came from.

However, it’s pretty easy for the message to be encrypted in such a way that only Digital Cash Account Providers can decrypt the message and reference. In that case, the message and reference will appear to the Bank of England as follows:

Sender Account IDReceiver AccountAmountDate & TimeMessage & Reference08-32-22-1025161009-21-22-50361922£250.002016-05-29EnCt2d207add0ce9b431c0de97a

6072f995169db06bf0d207add0c

e9b431c0de97a602UBNGL+p+w

LiYetru1a+dUQezx0rJduamg+pJ

ddlB8A0eLH+CZZn4ALvcYEiifO+

7FHP84+fo1i0LlWAIwEmS

Now the Bank of England has no idea who the payment is from and to.

Only the DCA Providers would know the decryption password to turn that jumble of letters back into a meaningful message.

The only way the Bank of England could read the information from this message would be upon its receipt of an order from a court of law requiring the DCA Provider to reveal who the payment was made to (for example, as part of a police or fraud investigation).

Even Further Anonymity

In theory it’s possible to take encryption further, to the point that when, in the example above, Louis makes a payment to Ella, then:

Louis’s DCA Provider doesn’t know who Louis is making a payment to

The Bank of England knows that the payment has been made between two accounts, but doesn’t know who owns those accounts (as above).

Ella’s DCA Provider knows she received a payment, but not who it is from.

Only Louis can see that he made a payment to Ella

Only Ella can see that the payment into her account came from Louis.

My knowledge of encryption doesn’t stretch far enough to specify how that arrangement would work, but I’m fairly confident that this would be child’s play for security specialists. If anyone with that kind of knowledge or experiences wishes to develop the idea further, I’d be happy to discuss it.

There is also the possibility that the authorities might block such a high level of privacy, as it would make it difficult to trace fraud, payments to terrorists and so on. But the lower level of security, whereby the Bank of England does not store any data on who made the transactions, should be perfectly acceptable.

What about Bitcoin?

In theory, Bitcoin or a currency modelled on its underlying blockchain technology, is more anonymous than the system above. Anyone can get a Bitcoin address without having to provide any details that would personally identify you. But there are limitations to this anonymity.

Bitcoin (and any distributed ledger currency) makes the entire transactions data – the blockchain – publicly available to the whole world. The data itself is anonymous, as it just records transfers of certain amounts from one ‘address’ (a bit like an account) to another, with no personal details attached. There are many pros to Bitcoin and its like, but a major con is if someone finds a way to link your identity to a single transaction, it’s possible for them to follow the chain to find all your other transactions. People are developing ways around this, but at the moment using Bitcoin as a genuinely anonymous payment system requires a high level of technological sophistication. If you’re interested in more about Bitcoin privacy, it’s well worth reading this (external) article: How Anonymous is Bitcoin?

In contrast, the Transactions Data in the system we outlined above is private: only the Bank of England has the full transactions history (and your DCA Provider will have the portion of the history that relates to your transactions). So in this sense, a centralised digital cash system may provide more privacy and anonymity than a distributed ledger system.

One other major con for Bitcoin-style currencies is that if you lose your private key (effectively the password that allows you to spend your bitcoin or other cryptocurrency), you’ve lost access to the money forever. There is no possibility of recovering the password. Also, if you get hacked and your private key is stolen, there is no way to reverse the transaction or recover those funds. It’s worth being aware that there are these tradeoffs if you want to move towards complete anonymity.

In Summary

With a simple bit of database design, we’ve got a system where the Bank of England only has records of transactions between anonymous payment accounts. It could only require a DCA Provider to reveal who you are if it had an order from a court, which is the same level of anonymity you get with normal bank deposit accounts.

It may be possible to go even further so that not even your Digital Cash Account Provider knows who you’re making payments to. In other words, you would be the only person able to ‘unlock’ your transactions data.

Is this enough to address the privacy concerns around digital cash? Let me know your thoughts in the comments below.