Finance and DemocracyUK

7 August 2025

February 28, 2024

Sitting at the very heart of the financial system, collateral frameworks are some of the most powerful tools central banks have. But by not considering the environmental impact of the collateral it accepts, the Bank of England is handing an advantage to damaging sectors like fossil fuels. Our new paper explores how the Bank can change the rules for a greener financial system.

Central bank money (termed ‘reserves’) lies at the centre of the monetary and financial system. Used by commercial banks to make payments between each other, it is a form of publicly-issued money, supplied by the central bank, that is essential for the functioning of the financial system.

The Bank of England supplies reserves to banks through a range of facilities, and the volumes supplied are no small sum. Since March 2014, the Bank of England has supplied almost £165 billion in reserves to the banking system through its regular lending facility alone, the Indexed Long-Term Repo Facility (ILTR).

Reserves are not just gifted however, they’re lent to banks in exchange for financial assets – like mortgage loans, government bonds and corporate bonds – as collateral, which the central bank can sell in the instance a borrower can’t repay. The rulebook for this lending, which outlines which assets are accepted and on what terms, is known as the ‘collateral framework’.

The rules set for lending reserves have important implications for a greener and more just financial system. The assets that the central bank accepts as collateral, and on more favourable terms, are seen as more valuable by the banking system, as they can be more easily exchanged for central bank reserves in times of stress. This impact extends far beyond central banks’ own balance sheets. Financial markets use the collateral frameworks of major central banks’ as a basis for their own collateral-based lending, which is a major way in which banks fund their activities. As a result, assets accepted as collateral by the central bank, and on more favourable terms, are in greater demand by banks and investors and have been found to benefit from higher asset prices and lower yields, meaning that their issuers – such as governments or corporations – are able to raise financing more cheaply.

The terms on which financial institutions access central bank liquidity are only likely to become more important as the Bank of England continues to reduce the overall amount of reserves in the system through quantitative tightening. The growing financial stability risk of the non-bank or ‘market-based’ financial sector is also likely to increase the direct influence of the Bank’s collateral rules – with the 2022 ‘LDI’ crisis in the UK pensions industry leading the Bank to announce plans for a new tool for non-bank financial institutions to access central bank liquidity. Reforms that would increase the amount of collateral banks are required to hold are introduced in the future (as outlined in a recent Positive Money blog, this could also give the collateral framework even greater power to green the whole financial system).

The environmental impact of the Bank of England’s collateral framework

Positive Money’s new paper argues that by not accounting for the environmental impact of the assets accepted as collateral, the Bank is implicitly subsidising the most environmentally damaging companies, by making it easier for them to raise financing. Most of the assets eligible in the Bank of England’s collateral framework are government bonds, mortgage loans, and other forms of consumer loans, but the Bank also accepts a number of corporate bonds – including from companies driving climate change and nature loss at scale.

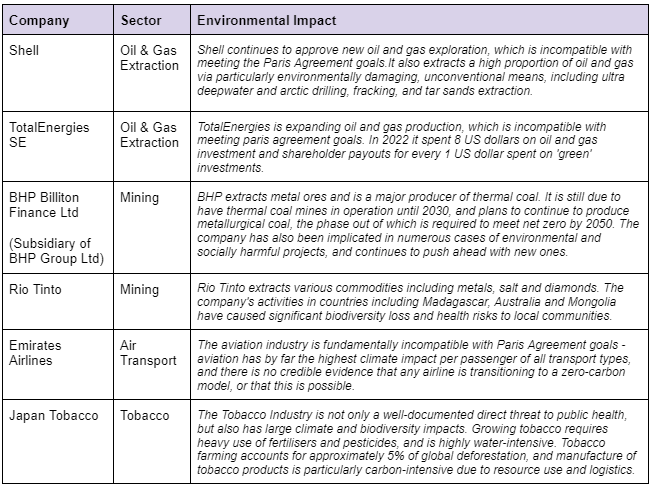

Investigating the Bank of England’s list of assets eligible as collateral, we found that the Bank accepts bonds from a range of companies with huge environmental footprints:

Several of these companies have been implicated in severe human rights and environmental justice violations – dimensions that central banks’ ought to be considering going forward.

As well as contributing to ecological breakdown, awarding the benefits of collateral eligibility to such companies’ jeopardises the Bank’s ability to achieve its key objectives for price and financial stability. As is now well-known, climate change and biodiversity loss present fundamental risks to financial stability, as assets from companies’ whose primary activities are incompatible with meeting climate goals are likely to become stranded. They also pose a fundamental risk to price stability due to the inflationary impacts of fossil fuel reliance and climate impacts, as set out in Positive Money’s recent report, ‘Inflation as an Ecological Phenomenon’. The Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee also has an explicit mandate to support the transition to net-zero.

Other central Banks, including the European Central Bank, the People’s Bank of China, and the Bank of Hungary, have already begun the process of greening their collateral frameworks. But as Positive Money’s paper highlights, the Bank of England has an opportunity to learn from the approaches taken by other central banks and implement a more effective method of greening.

How to green the collateral framework

Our paper sets out some key steps that the Bank of England should take to green it’s collateral framework:

Firstly, the Bank should develop a framework to define the ‘greenness’ of assets by evaluating their environmental footprint, using, for instance, carbon emissions and biodiversity impact metrics associated with the asset and the issuer. This contrasts with attempting to estimate the financial risk posed to assets by climate change and biodiversity loss, which cannot easily be quantified and tend to vastly underestimate risk. Such an approach is a major flaw of the ECB’s collateral greening programme that the Bank of England can avoid.

Secondly, the Bank should exclude assets from its collateral framework from issuers whose primary activities are not compatible with the UK’s environmental goals. This would follow the precedent set for climate-based exclusions from the Bank’s Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme, which excluded assets from issuers with coal mining activities. But the Bank should go beyond coal to exclude all activities that are not aligned with both climate and biodiversity goals – meaning, at a minimum, fossil fuel producers. Given that corporate assets form a relatively small proportion of all eligible collateral assets, excluding these assets should be easily implementable and other, greener assets could be made eligible in their place.

Finally, the Bank should adjust the terms on which it accepts assets, according to their environmental footprint. These terms are set by ‘haircuts’, which simply means the discount applied to the market value of an asset. For instance, if a 20% haircut is applied to an asset with a market value of £100, the borrowing bank would receive £80 in reserves in exchange. Assets that are deemed more risky have a higher haircut applied – this should reflect an assets environmental footprint, too.

Whilst considering the treatment of other assets such as public bonds and mortgage loans is not within the scope of this paper, the implications of this treatment for global climate mitigation, adaptation and environmental justice, is an important avenue for further consideration. As explained in a recent paper by Yannis Dafermos, the treatment of public bonds as collateral by global North central banks impact upon the financing conditions of global South governments, and integrating environmental considerations into the collateral framework for public bonds must be done in a way that does not penalise countries and communities who have historically contributed least to climate change, and yet suffer the worst impacts, and instead reduces their cost of borrowing.

Sign-up to our mailing list for regular updates, and donate to support our work fighting for a money and banking system that enables a fair, sustainable and democratic economy.