UKGlobal

27 January 2026

In line with the 38% Energy Profits Levy, a windfall tax targeting UK retail net income would be expected to raise £11.3bn this year from Britain’s big four banks alone, without harming the sector’s international competitiveness.*

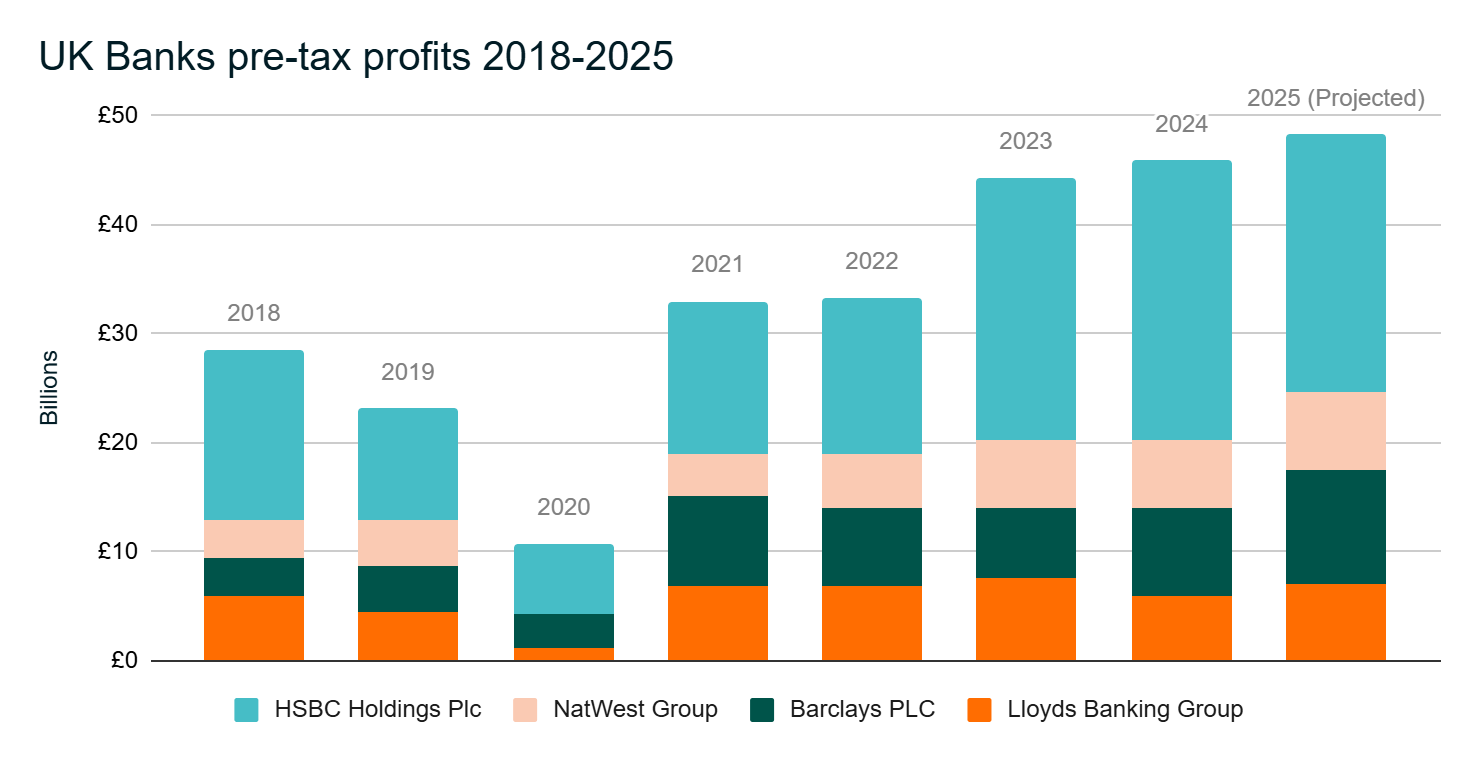

Higher interest rates have handed record profits to banks, with the UK’s big four - HSBC, Barclays, Lloyds, and NatWest - reporting pre-tax profits of £45.9bn for 2024. This is equal to around £650 per person in the UK, more than four times the profits recorded in 2020, before rates started rising, and nearly double the £25.6bn average annual profits of 2018-21.

The big four banks may be on track to smash another record, having just reported profits of £24.1bn for the first half of 2025.*

| Bank | H1 2025 profit before tax (£bn) |

|

Barclays |

5.2 |

|

HSBC |

11.8 |

|

NatWest |

3.5 |

|

Lloyds |

3.5 |

|

Total |

24.1 |

Projected pre-tax profits for 2025 derived from doubling banks’ 2025 half-year results.

These record profits are being fuelled by the Bank of England paying interest on hundreds of billions of pounds of risk-free reserves held by banks, for which the public foots the bill. While cutting back on public spending, the Treasury has quietly paid £85.9bn to cover the Bank of England’s losses between the end of 2022 and March 2025, and is forecast to pay a further £108.7bn between 2025-6 and 2029-30 - an average of £21.7bn a year for the next five years.

Given the structurally uncompetitive market for deposits, banks have managed to resist passing on this income to customers. Astonishingly, there are around £450bn of deposits in the UK which pay no interest at all, with around £300bn held by households and £150bn held by non-financial businesses. This provides an exorbitant free lunch for banks, which can get more than 4% on their risk-free reserves from the Bank of England, and can be thought of as a hidden tax on the public paid to banks currently worth nearly £20bn a year.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves could tax banks’ unearned windfalls back, as Margaret Thatcher did back in the 1980s, reflecting, in her words, the fact that banks “had made their large profits as a result of our policy of high interest rates rather than because of increased efficiency or better service to the customer.” This rings true today as despite record profits, banks have ruthlessly cut back on services for customers, with 6,443 branch closures since 2015, representing 64% of branches.

Several European countries, including Spain, the Netherlands, and Czechia have introduced higher taxes on banks’ windfall profits. The UK should follow suit, and can do so without harming international competitiveness.

Like in Spain, the UK government could introduce a windfall levy on banks’ net interest income (NII) and net commissions above a certain threshold (€800m in Spain).

The big four have reported retail net income of more than £16.5bn from their domestic retail operations for the first half of this year. If this trend continues, a 38% windfall levy (in line with the successful Energy Profits Levy on windfalls enjoyed by oil and gas companies) on UK retail net income above a threshold of £800m could be expected to raise £11.3bn from Britain’s ‘big four’ banks alone.

|

UK retail NII for H1 2025 (£mn) |

Total UK retail net income for H1 2025 (£mn) |

Estimated UK retail net income FY 2025 (£mn) |

2025 UK retail net income above threshold (£mn) |

Revenue from 38% levy (£m) |

|

|

2,865 |

3,239 |

6,478 |

5,678 |

2,158 |

|

|

4,203 |

4,863 |

9,726 |

8,926 |

3,392 |

|

|

4,709 |

5,279 |

10,558 |

9,758 |

3,708 |

|

|

2,922 |

3,134 |

6,268 |

5,468 |

2,078 |

|

|

Total |

14,699 |

16,515 |

33,030 |

29,830 |

11,336 |

As we have suggested in the past, the government could simply raise the existing bank profits surcharge in line with the Energy Profits Levy. This surcharge was introduced in 2015 in recognition of the need for banks to “make a fair contribution in respect of the potential risks they pose to the UK financial system and wider economy.” The previous government slashed the surcharge by 60%, from 8% to 3%, and we support calls for this to be reversed.

However, for better or worse, this government’s Financial Services Strategy has made it clear they want to prioritise the ‘competitiveness’ of the sector. We have already seen banks threaten to move business abroad amid rumours of higher taxes. Given that the bank surcharge is levied on all profits, opponents may be able to argue that banks would respond by booking their global and/or investment banking operations elsewhere.

To mitigate this, we are therefore proposing that the government emulates the Spanish tax on net interest income and net commissions, but specifically targets UK retail banking net income above a threshold at a rate of 38%, in line with the Energy Profits Levy.

This would capture the windfalls banks have made at the expense of the British public, while eliminating any possible threat of banks responding by moving their operations abroad. If a bank exits the UK retail banking market, their assets and liabilities, as well as profits and tax liabilities, would simply be acquired by a competitor - nothing of real value would be lost for the UK, and equally nothing of value would be gained for the exiting bank.

With such a policy in place, the government could, if it so wishes, reduce or even eliminate the bank profits surcharge, though we would caution against this.

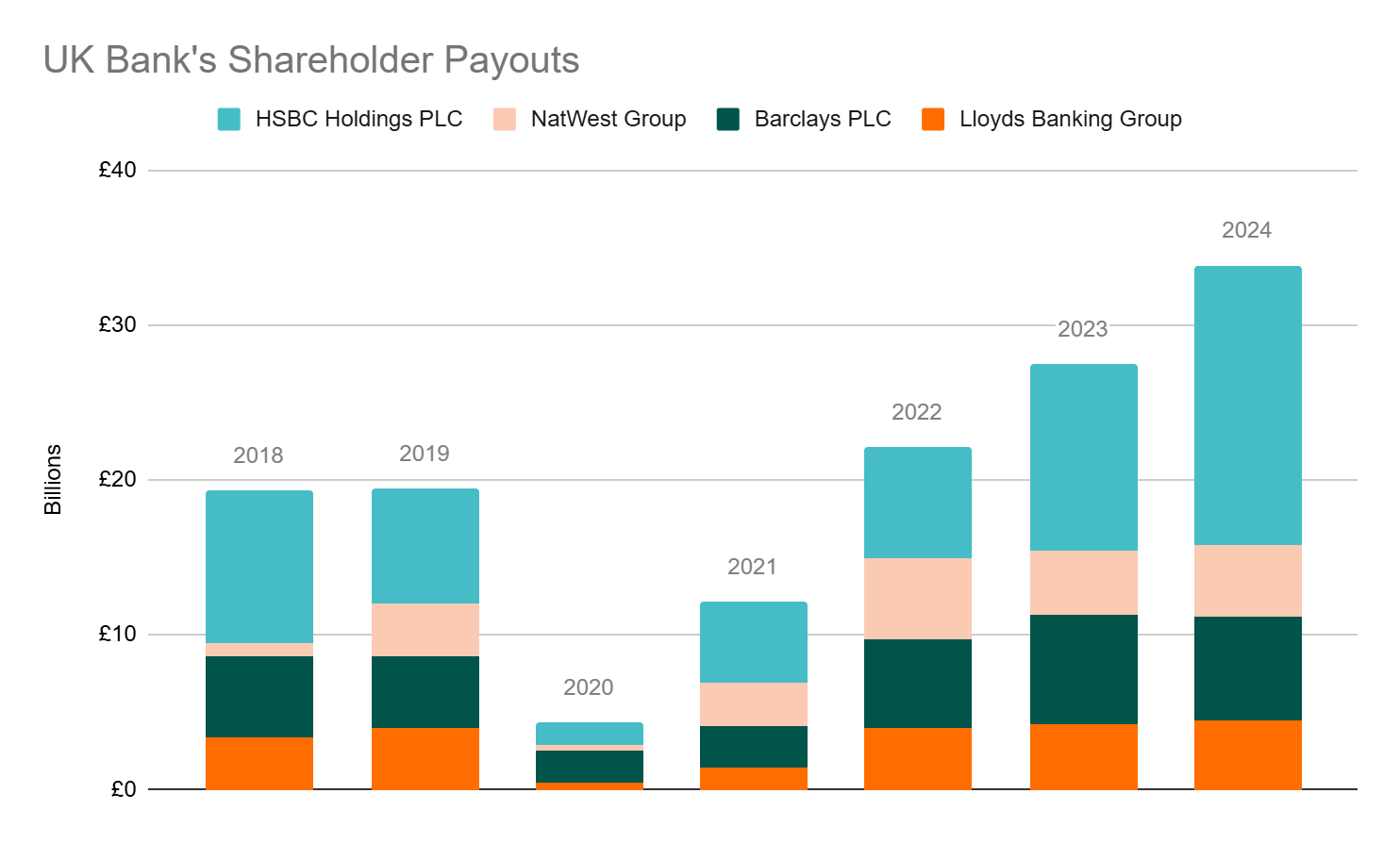

A 38% levy on net interest income above a threshold of £800m would leave banks with enough income to cover costs, including impairments (money set aside to cover potential losses). Banks’ attempts to maintain margins with higher rates for borrowers would be limited by competition in lending markets, which are relatively competitive, particularly for mortgages. The hit would thus temporarily be borne by shareholders, who may have to forego the dividends and share buybacks they’ve enjoyed so much in recent years. This may be reflected in bank shares trading lower on secondary markets, but this is unlikely to have any negative impact on the economy. The market value of bank shares have consistently traded below the book value of their assets, and this does not seem to have affected banks’ ability to lend. Lower share prices are only an issue if banks are required to issue new shares but, as the Bank of England maintains, banks are well-capitalised, and are required to set aside money for losses via impairments anyway, so it is unlikely that banks will find themselves needing to raise more equity capital anytime soon.

Figures are based include dividend payments and amounts spent on share buy-backs in each financial year, based on Positive Money’s analysis of cash-flow statements in company annual reports.

It should go without saying that there are much better uses for billions of pounds a year than lining the pockets of shareholders. The £11.3bn a windfall tax could raise is more than £150 per person in the UK, and would cover the government reversing the welfare reforms, two child benefit cap and winter fuel cuts, or pay the salaries of around 300,000 nurses. Any of this would be much better for the UK economy.

While banks must ultimately be profitable, there is no compelling reason why we should allow banks to extract such large rents from the rest of the economy through their monopoly position in issuing the money we use for payments, the provision of which is best thought of as a public utility. Windfall taxes make sense for both energy companies and banks. Add your name to the petition to #TaxTheBanks today → bit.ly/TaxTheBanks

*figures in this blog are based on banks declared 2025 Q2 results. The updated headline figure based on Q3 results can be found in our latest press release