How We Got Here

Laws that make it illegal for you to print your own £5 or £10 notes have been in place since 1844.

Laws that make it illegal for you to print your own £5 or £10 notes have been in place since 1844. But when these laws were passed, they overlooked the fact that money can also exist in the form of bank deposits (the numbers in people’s bank accounts). Because of this oversight, banks now have the power to create money through a simple accounting entry. As a result, today almost all money exists as electronic bank deposits, and is created when banks make loans.

A Short History of Money in the UK

Two centuries ago, only the government was legally allowed to create metal coins. But trying to keep metal coins safe or carrying them around was inconvenient, so people would typically deposit their coins with the local jeweller or goldsmith, who would have a safe. Eventually, these goldsmiths started to focus more on holding money and valuables for customers than on actually making jewellery. They became the first bankers.

A customer putting coins into the new ‘bank’ would be given a piece of paper stating the value of coins deposited, a little like the one on the left. If the customer wanted to spend his money, he could take the piece of paper to the bank, get the coins back, and then spend them in the local shops.

However, the shopkeeper who received the coins would usually take them straight back to the bank for safety. To save a trip to the bank, shopkeepers would simply accept the paper receipts as payment instead. As long as people trusted the bank that issued the receipts, businesses and individuals would be happy to accept the receipts, safe in the knowledge that they would be able to get the coins out of the bank whenever they needed to.

Over time, the paper receipts became accepted as being as good as metal money. People forgot that they were just a substitute for money and saw them as being equivalent to the coins.

The goldsmiths soon noticed that the bulk of the coins placed in their vaults were never taken out. Only a small percentage of deposits were ever asked for at any particular time. This opened up a profit opportunity – if the bank had £1,000 of coins in the vault, but customers only withdrew a maximum of £100 on any one day, then the other £900 in the vault was spare. The goldsmith could lend out that extra £900 to borrowers, and make a profit by charging interest on the loan.

However, rather than lend the coins, the goldsmiths would write out new paper receipts for borrowers. This meant that the bank could issue paper receipts to other borrowers without needing many – or even any – coins in the vault. With only £1,000 of coins in the vault the bank could lend out £2,000, £4,000 or as much paper money as it dared too. (Of course, the banks still faced some restrictions – if too many people came to get their money back at the same time then it would be obvious that the bank didn’t have enough money to repay everyone.)

The banks had acquired the power to create a substitute for the metal money created by the government. In effect, they had acquired the power to create money.

1844 Bank Charter Act

The hunt for profit drove banks to issue and lend too much paper money. This increased the amount of money in the economy, pushing up prices and de-stabilising financial markets. (One crisis was particularly embarrassing for the Bank of England – in 1839 it had to borrow £2 million of gold from France to rescue failing banks).

In 1844, the government of the day, led by Sir Robert Peel, realised that they had allowed the power to create money to slip into the hands of banks. They passed a law to take back control over the creation of bank notes. This law, the Bank Charter Act, prohibited the private sector from (literally) printing money, transferring this power to the Bank of England.

The Flaws in the Law

However, the 1844 Bank Charter Act only stopped the creation of paper bank notes – it didn’t refer to other substitutes for money, such as bank deposits. Because of this oversight, banks could still create ‘bank deposits’ by making loans – and so they could still create money simply by opening accounts for people or companies and adding numbers to them. With growth in the use of cheques these deposits could be transferred to make payments, and therefore used as money. When a cheque is used to make a payment, no cash is withdrawn from the bank. Instead, the paying bank talks to the receiving bank to settle any differences between them once all customers’ payments in both directions have been cancelled out against each other. This means that payments can be made even if the bank has only a fraction of the money that depositors believe they have in their accounts. However, despite the rise of cheques, cash was still used for a large proportion of transactions, and so banks were limited in the amount of money they could create in case they ran out of physical cash.

And then there were computers…

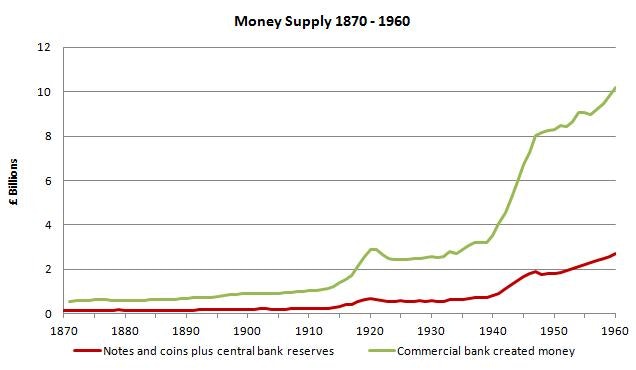

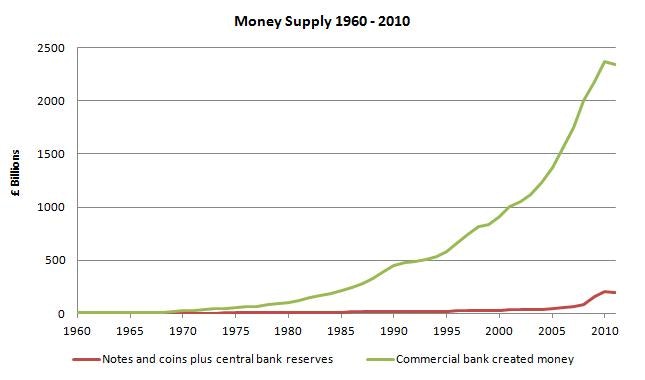

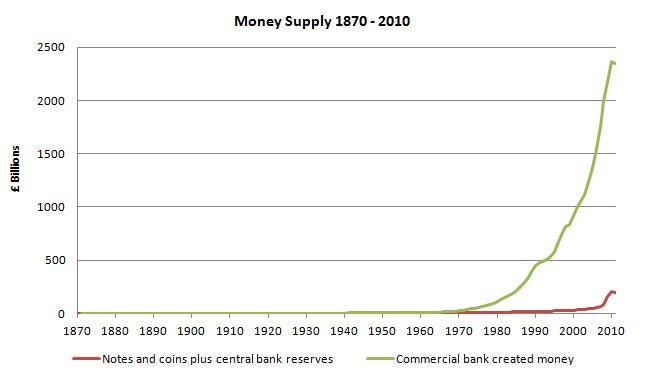

Following on in the spirit of financial innovation, after cheques came credit and debit cards, electronic fund transfers and internet banking. Cheques are now irrelevant as a means of payment: today over 99% of payments (by value) are made electronically. With the rise of computers and financial deregulation beginning in the 1970s, banks could really let loose. The following charts show how much money (in green) the banks created, relative to the amount of government-created money (in red):

Even those who know that banks are able to create money often assume that banks are obliged to possess a sum corresponding to a significant fraction of their liabilities (their customers’ deposits) in liquid assets (i.e. in cash, or a form that can be rapidly converted into cash). In fact, such laws were weakened in the 1980s in response to lobbying from the industry (although some effort is now being made to re-impose such rules in the aftermath of the crisis).

The situation today

The electronic numbers in your bank account do not represent a specific pile of cash with your name on it. They simply give you a right to demand that the bank gives you physical cash or makes an electronic payment on your behalf. In fact, if you and a lot of other customers demanded your money back at the same time (a bank run) it would soon become apparent that the bank does not actually have your money. For example, on the 31st of January 2007 banks held just £12.50 of reserve money (in the form of electronic money held at the Bank of England) for every £1,000 of deposits in their customers’ accounts.

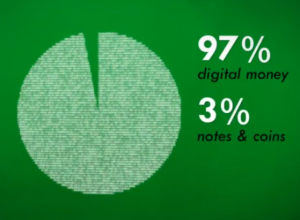

Deposit money now makes up over 97% of all the money in the economy – around £2.1 trillion, compared to only £60 billion of cash.1 By value of payments, bank deposits are used for 99.91% of transactions and transfers, with cash being used for just 0.09% of transfers2. Consequently, the physical currency issued by the state has been almost entirely replaced by a digital currency issued by private companies. The UK’s money supply has been effectively privatised.

NEXT: Watch our Banking 101 Video Course to learn how banks create money, or discover how we can stop them creating money.

What about bank notes in Scotland and Northern Ireland?

Learn More

Overview

The Proof that banks create money

The way that money is taught in universities is often very inaccurate. These papers and sources from central bankers and other experts show how the system really works.

How Much Money Have Banks Created?

From the time when the Bank of England was formed in 1694, it took over 300 years for banks to create the first trillion pounds. It took them only 8 years to create the second trillion.

The Technical Details - how money works

Video Course: Banking 101

This free animated video course (total 57 minutes) explains how the modern banking system creates money, and what limits how much money banks can create.

Advanced: All the technical details

This section covers all the nitty-gritty details of money creation by banks. We cover the three types of money, how balance sheets work, how central and commercial banks create – and destroy – money and what is wrong about the textbooks taught in universities. Read more…

Books

Book: Where Does Money Come From?

“Refreshing and clear. The way monetary economics and banking is taught in many – maybe most – universities is very misleading and this book helps people explain how the mechanics of the system work.”

– Professor David Miles, Monetary Policy Committee, Bank of England

Book: Modernising Money

Why our monetary system is broken, and how to fix it.

“Money is a social invention, indeed among the most important of all social inventions. At present the right to create money has been handed over to the private businesses we call banks. But this is not the only way we could create money and, as recent experience suggests, it may be far from the best one. Read this book with an open mind and you will understand why.”

– Martin Wolf, Chief Economics Commentator, Financial Times

Further Resources

Papers and videos from:

The Bank of England

The International Monetary Fund

Lord Adair Turner, former chairman of the UK’s Financial Services Authority

Other professors and experts in the monetary system