The future of moneyEU

12 January 2026

The dollar is the key currency in the international monetary system and plays an enormous role in the European financial system. In times of crisis, Europe has benefited from the Federal Reserve’s interventions to stabilise the system in times of financial distress. However, mounting political pressure from Trump’s administration on the Federal Reserve puts this role into question, which poses serious risks to European financial stability.

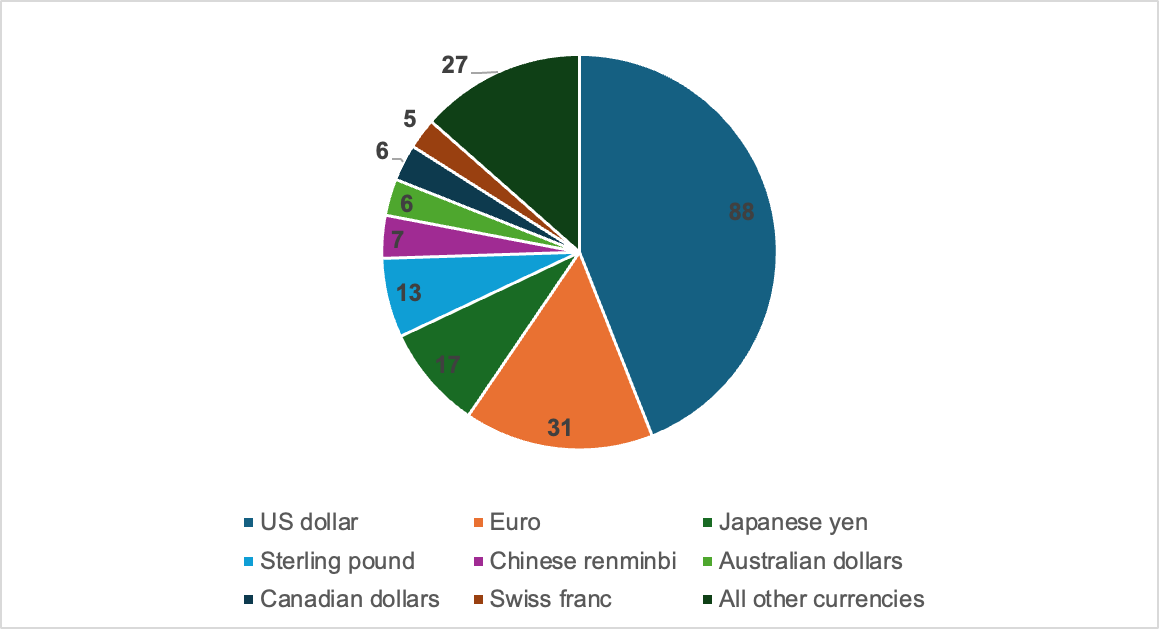

The European Central Bank (ECB) has recently published its annual report on the international role of the euro. It comes as no surprise that the dollar keeps its role as the key-currency of the world economy, and the euro appears as the second most important currency. Yet, for those not familiar with these discussions, it is important to highlight the huge gap between the international relevance of these two currencies. The US dollar is used for nothing less than 88% of the operations in the foreign exchange market, the euro coming at a distant second place at 31% (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Turnover, Global foreign exchange market (%)

Source: BIS Triennial Survey (2022).

Note: since foreign exchange operations involve two currencies, the total is 200%.

When it comes to international reserves, the share of the US dollar has declined over the last decade but still stands at 58%, while the euro accounts for 20%. In the case of international debt securities, roughly two-thirds are denominated in US dollars and one-fifth in euros. More than half of world trade is invoiced in US dollars.

The dominance of the dollar is therefore unambiguous, and one cannot underestimate the consequences for the world economy. On the one hand, the reliance on a key-currency undoubtedly facilitates international transactions, and provides an anchor for global financial wealth. On the other hand, when this key-currency is the national currency of a country, it creates deep asymmetries. It forges huge benefits for the issuing country, and immense problems and risks for the rest of the world - especially for the Global South (for details, see our other blogs on the topic).

Aware of the benefits engendered by the dollar hegemony, the US government - along with its central bank (the Federal Reserve) - has been implementing policies aimed at the maintenance of this role of the US dollar, for more than 80 years. In 1944, for example, US representatives at the Bretton Woods Conference made diplomatic and political efforts to establish a dollar-centered International Monetary System. Meanwhile, bilateral agreements have also been made to foment the usage of the US dollar (including even military agreements), as well as unilateral decisions related to US monetary policy such as Volcker's big hike in the US interest rates in 1979.

With the outbreak of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) (2007-8), one of the main policies implemented by the US to give some stability to the global system and assure the maintenance of the dollar’s dominance, was the establishment of ‘swap lines’ with 14 countries. These are pre-approved arrangements in which the Fed provides a certain amount of US dollars to another central bank in exchange for an equivalent amount of its national currency, for a specified period of time. At the end of this period, the currencies are swapped back, and the pre-defined interest is paid.

This was important because countries having a lack of US dollars could have easy access to much-needed US dollars provided by the Federal Reserve. However, this policy unsurprisingly reproduced the asymmetries of the world economy, because the swap lines were offered almost exclusively to Global North countries. Currently, only the swap lines with some of the central banks - among which the ECB - became permanent lines (i.e. standing arrangements). Still, they are important to curb the instability which may be provoked, even in Global North countries, in a situation of US dollar shortage, as was the case during the Covid-19 pandemic.

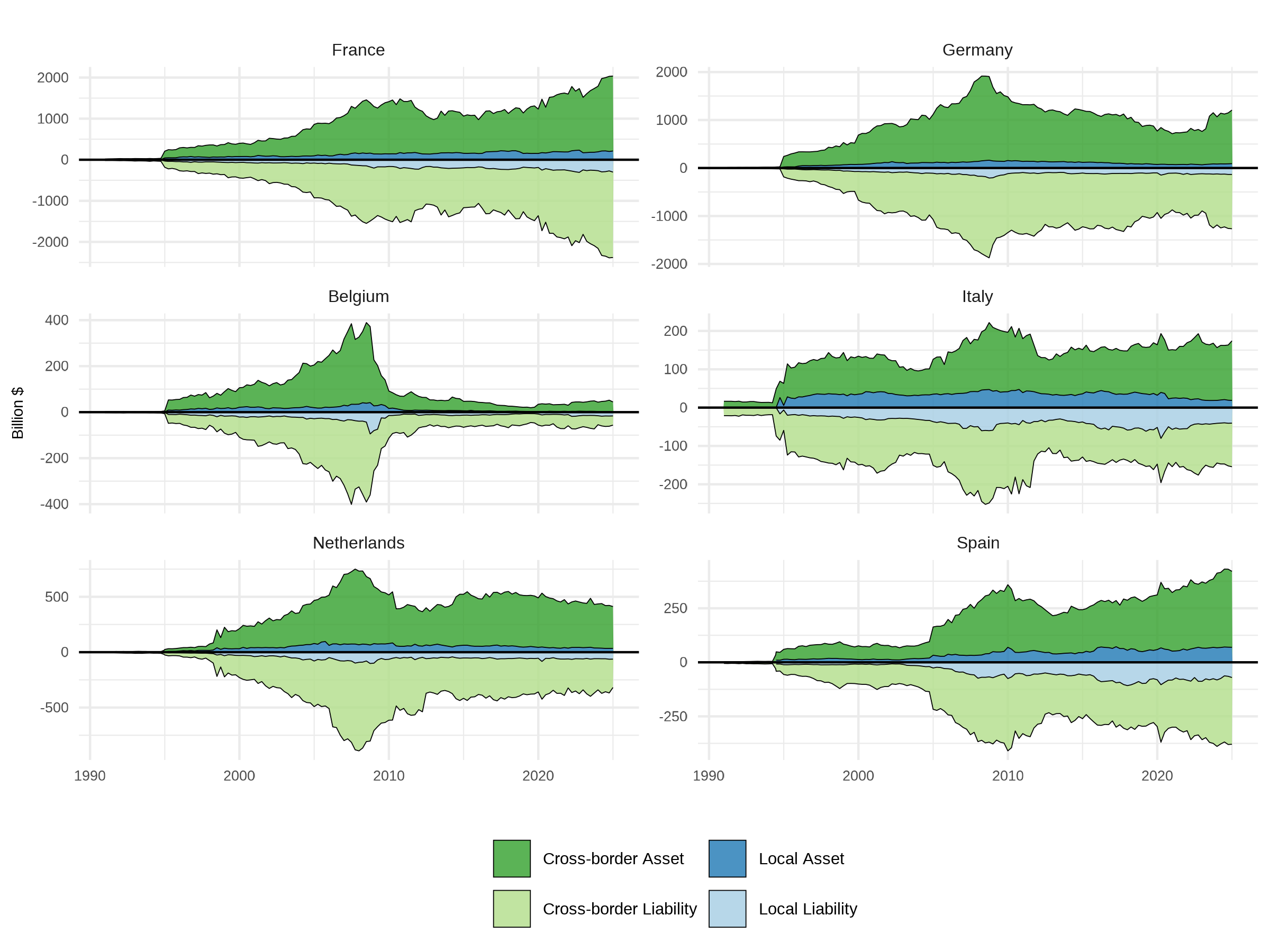

In this asymmetric system, European banks have historically played, and still play, a central role in dollar intermediation. In the run up to the GFC, European banks purchased huge amounts of dollar-denominated assets, which included residential mortgage backed securities, financing these purchases by borrowing in short-term wholesale markets. This placed European banks in the eye of the financial storm. While this dollar intermediating role receded after the GFC, European banks are still an important player, as the figure below illustrates. For example, French banks hold more than two trillion dollars in combined dollar-denominated assets and liabilities.

Figure 2: European banks’ dollar assets and liabilities (1990-2025)

Source: BIS. Own elaboration.

According to economists from the Bank for International Settlements, most of this dollar intermediation takes place outside of the US. A recent ECB brief showed that 17% of euro area banks’ funding is dollar denominated. This dollar funding takes place mostly through short-term wholesale markets, exposing it to rollover risk - meaning the difficulty of replacing maturing debt - during times of financial instability. As the stress test conducted in 2019 showed, euro area banks' survival periods - the days a bank can cover cash going out minus cash going in using its liquid assets - in dollars were much shorter than in euros. Under the extreme stress scenario, some banks’ dollar liquidity would run out in under thirty days. Some banks had no dollar high-quality liquid assets (HQLA), relying particularly on private foreign exchange (FX) swaps. Importantly, private markets for FX swaps tend to dry up during financial stress periods.

What is especially relevant here is that, while the ECB faces no constraints in playing the lender-of-last-resort role in euros, it depends on the abovementioned liquidity swaps from the Federal Reserve to do so in dollars.That is precisely what happened during Covid-19, when FX swap markets dried up until the ECB started to provide dollars at favourable pricing on a daily basis on the 23 March 2020, given the coordinated central bank action to enhance liquidity swaps.

It is not only European banks, but the whole European financial system, that is highly reliant on the dollar. Between 2015 and 2023, European investors - including pension funds and insurance companies—increased their US bond holdings by $1.3 trillion. These dollar positions are then hedged through short-term FX swaps, which, in times of financial stress, can become prohibitively expensive. This means that investors either pay a very high price for hedging their dollar positions or have to leave them unhedged. The latter means that, in the event of movements in the dollar exchange rate, these investors can face huge losses. The unequivocal perception is that the European financial system is hooked up on the dollar, and, therefore highly dependent on the Federal Reserve playing a leading role in stabilising the system in times of financial distress.

When Donald Trump started his second mandate, however, the “harmonious pilotage” between the US government and the Fed for the preservation of the US dominance was seriously shaken. The US president started making several declarations against the Fed, raising rumours that he could even anticipate the replacement of the Chairman of the Fed Jerome Powell. The next chair of the Fed will be appointed by Trump in May 2026. This has created strong uncertainties around the swap lines provided by the Fed. Important analysts and institutions are raising discussions about this risk, indicating that it might weaken the dollar dominance and create strong financial instability.

While decisions on central bank liquidity swaps come from the Fed, it is the US Congress that grants the Federal Reserve its authority. On top of that, the Fed is exposed to political pressure from Congress, to which it has already bowed by withdrawing the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). Given the willingness of the current administration to leverage its privileged position to create instability to obtain geoeconomic means—as we are seeing with the case of tariffs—there is a dangerous possibility that, in the event of financial distress, dollar liquidity from the Fed, if available, might imply both huge economic and non-economic costs.

Given this dollar dominance, one might question the current upbeat atmosphere about a “global euro” moment. While the promotion of the role of the euro is a discussion worth having, the uncertainty regarding the role of the dollar poses more risks than opportunities in the short-to-medium-term. The economist Charles Kindelberger famously said that: “the 1929 depression was so wide, so deep, and so long because the international economic system was rendered unstable by British inability and US unwillingness to assume responsibility for stabilizing it”. The ECB must now prepare for the possibility of not counting on its privileged access to dollar liquidity in times of financial stress. This entails an imperative to deal with the currently existing dollar risks in the European financial system.