QE or not to QE? Soaring inequality shows it’s time for a new macroeconomic approach

February 11, 2021

If you just looked at property and financial markets, you’d be forgiven for thinking that we weren’t in the midst of a global pandemic which has left millions unemployed and large swathes of the economy locked down. UK house prices reached record highs in 2020, averaging more than £250,000 across the country, and more than £500,000 in London. Various asset classes seem to be surging on both sides of the Atlantic, with financial indices reaching new heights, and seemingly boundless speculative mania symbolised by stocks like Tesla and GameStop, as well as cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin.

How have asset prices become so detached from the ‘fundamentals’ that are supposed to drive them, such as earnings and incomes, which have suffered as Covid-19 has forced economies into lockdown? This isn’t a new story, but a continuation of the previous decade, where economies and wages have stagnated, yet stock markets and property prices have soared.

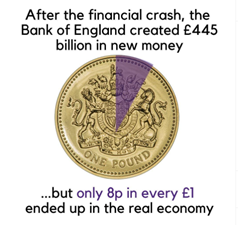

One of the main drivers of this is quantitative easing (QE), the ‘unconventional’ monetary policy introduced by central banks to respond to the last financial crisis and the great recession. QE involves central banks creating new money to buy financial assets, typically government debt. At the same time as we were being told there’s “no money left” for the government to spend, between 2009 and 2016 the Bank of England flooded financial markets with £445 billion of newly created QE money.

This ‘wave of liquidity’ propped up asset prices, with the Bank of England suggesting that real house and share prices in 2014 would have been 25% and 22% lower respectively without it. Because assets are of course disproportionately owned by the wealthiest, this has turbocharged inequality. The Bank of England’s own analysis estimated that the wealthiest 10% of households were enriched by £350,000 each during the first five years of QE – more than 100 times the benefit seen by the poorest 10%. This windfall for the wealthy has likely grown much higher in the years since, and we can expect the gains to be even more shocking for the very top percentiles.

For the Bank of England, this asset price inflation and inequality isn’t an unwanted side-effect of quantitative easing – it’s a design feature. In the Bank’s own words, an objective of QE is to “stimulate the economy by boosting a wide range of financial asset prices … when demand for financial assets is high, with more people wanting to buy them, the value of these assets increases. This makes businesses and households holding shares wealthier – making them more likely to spend more, boosting economic activity.”

As the Bank of England has explained, one of the main ways it thinks QE drives this wealth effect is through the portfolio rebalancing channel. The theory is that new money injected into financial markets will see bondholders reinvesting funds into assets issued by companies, which should lead eventually to higher spending in the economy. Or as then Bank of England governor Mervyn King put it to the BBC in 2011:

“We are injecting £75 billion of money directly into the British economy. That will have an effect. Initially the people who get the money by selling government bonds to us will use that money to buy other things – they could buy goods, they could buy other financial assets, they can buy the securities companies issue in order to finance themselves. This will raise the prices of assets, it will make people better off in terms of wealth. This will gradually seep into the economy and raise demand, and will mean that the slowdown will be less severe than would otherwise have been the case.”

In other words, the thinking behind QE was essentially ‘trickle down’ economics. The idea being that if we pour enough money into financial markets, asset owners will become wealthier, and eventually this money will trickle down into the real economy.

But the Bank of England’s thinking hasn’t aged well. A decade of QE has shown the Bank’s approach to be successful in the goal of boosting asset prices (and by extension inequality), but a failure in igniting a sustainable economic recovery. It appears that very little of that £445 billion actually escaped asset prices, with analysis suggesting that for every £1 of QE, only 8p made it into the real economy. While it raised asset prices and made the wealthy wealthier, those who already have wealth are less likely to spend this money, opting instead to invest it into other assets, like property, pushing up the costs of housing for the rest of us.

One of the reasons QE was particularly ineffective and unequal is that fiscal policy (namely government spending) was pushing in a different direction. Over the same period the Bank of England created £445 billion to buy bonds, the Treasury was attempting to scale back borrowing and redistributive spending through austerity, in an attempt to ‘balance the books’. Not only did this mean there were fewer government bonds to meet demand, raising asset prices, it also meant that this newly created money effectively remained stuck in financial markets and property.

In 2020, as Covid forced governments to take unprecedented action to save lives, something seemed to change.

Rather than the government attempting to remove money from the economy through austerity, and the Bank of England being forced to make up for this with QE, the government was increasing borrowing at the same time the Bank was announcing it would buy government debt. In fact, the amounts the Bank announced it was going to create to buy up government debt, appeared to neatly match the amount the government would need to borrow.

In other words, the Bank of England now appeared to be using its power to create money to support public spending – what is often referred to as ‘monetary financing’. This enabled yields on government debt to be kept at record lows, despite a huge increase in spending, meaning that the government is actually set to spend less on interest payments than before the Covid crisis.

The money the Bank of England is now creating seems to be indirectly ending up in people’s pockets, through increased government spending on things like the furlough scheme.

What seems to be a greater degree of monetary-fiscal coordination is something we have been calling for and have therefore welcomed. But while QE seems to be playing a more positive role in supporting government spending, it was never designed for this. We still haven’t broken out of the dangerous asset price led growth model the policy was introduced to support.

Central banks have become relied on to effectively backstop financial markets, making stocks and property appear a one way bet. For investors, bad news has become good news. If the economy looks to be slowing down, central banks can be expected to inject more cash into financial markets with further QE, boosting asset prices even higher. It’s only a matter of time until this all comes crashing down.

So what should happen instead?

The creation of new central bank money, which QE entails, can take a variety of different forms and fulfil a range of different objectives. Rather than buying more government debt off the secondary market or even taking interest rates negative, the Bank of England could simply credit the Treasury with new money to spend directly. This money could then be invested in green infrastructure, or simply distributed to all citizens equally through a so-called ‘helicopter drop’ or universal basic income, for instance.

Positive Money has been championing such ideas over the years as better alternatives to ‘pure’ monetary policy, and we’ve seen growing support among even mainstream economists. Even BlackRock put forward such a proposal as a means of responding to the next downturn in 2019. The framework outlined by BlackRock involves the central bank financing government spending through what it calls a standing emergency fiscal facility (SEFF) when interest rates are at the lower bound (as they currently are in the UK). An institutional arrangement for this currently already exists in the UK through the government’s Ways and Means ‘overdraft’ account at the Bank of England, which was frequently used prior to the new millennium. The Bank has already extended the Ways and Means facility in response to the Covid crisis, but this has not yet been taken advantage of by the Treasury.

Crediting funds into the Ways and Means account for the government to spend would be a fairer and more sustainable means of supporting the economy and bringing inflation up to the Bank of England’s target, rather than further inflating asset prices with additional rounds of conventional QE, or the introduction of negative interest rates. £50 billion of new money spent into the real economy would have likely achieved more than £500 billion of conventional QE, with less negative side effects such as asset price inflation. With coronavirus exacerbating long-term deflationary trends, and the Bank of England expecting that Brexit could lead to additional spare economic capacity, such direct forms of monetary financing may actually be necessary to help get inflation up to the 2% target.

There could be a particularly strong opportunity for the Bank of England asset purchases to support the government’s National Infrastructure Strategy. Rather than using gilt purchases as a blunt instrument to inflate asset prices across the board, the Bank could undertake so-called ‘strategic QE’, using new central bank reserves to instead capitalise a national infrastructure bank geared towards investing in a fair green transition. Such fiscal-monetary coordination helped fund national investment banks throughout the twentieth century, and played a particularly key role in driving the recovery from the Great Depression and productive investment in countries such as New Zealand, Canada and the United States.

This is not to say we shouldn’t tax the wealthy, or that we should simply ‘print’ all of the money without issuing corresponding government bonds. Ultimately we need a combination of fair taxation, conventional borrowing and monetary financing all working in tandem. Because of central bank interventions in bond markets, it is cheaper than ever for the government to borrow. In fact, interest rates on some government bonds are even negative, meaning that investors are willing to pay the government to borrow from them.

Therefore it is possible to argue that paying for things by ‘printing money’ would be more expensive than simply borrowing the money, because the interest rate the Bank of England pays on banks’ reserves (the Base Rate – currently 0.1%) is higher than the interest rate on short-dated gilts.

But as Lord Adair Turner and others have pointed out, the decision to pay interest on reserves is a policy choice, and the Bank of England didn’t do this pre-financial crisis. Such reserve remuneration is arguably useful for helping central banks to exert control over monetary policy, so it may not be desirable to completely scrap it. But there is scope for a tiered reserve system, as the European Central Bank has introduced, which could be repurposed so that banks are not paid interest on excess reserves over a certain amount.

The Bank of England’s Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) review of QE, which Positive Money fed into, recently pointed to the failure of the Bank in informing the public how the policy is supposed to work and its effects. The IEO recommended that the BoE better communicates the rationale and evidence for its policy decisions. Crucially, this should mean the Bank openly exploring alternative policy tools, such as more direct forms of monetary financing.

More broadly, we need a new framework for macroeconomic policy, to ensure that we aren’t relying on monetary policy alone to keep the economy afloat, which will lead to even more burdensome private debt, inequality and instability. The Bank of England needs to be able to communicate when monetary policy is pushing on a string and the Treasury needs to step up with fiscal policy. It needs to be honest to the public about the ability of the central bank to support public spending, and to dispel the idea that money the government ‘owes to itself’ via QE needs to be paid back with counterproductive austerity measures.

As our director Fran Boait told Parliament’s Economic Affairs Committee this week, a new settlement for fiscal-monetary coordination will help us make sure the power to create money more equally benefits the whole of society, and helps, rather than hinders, efforts to overcome the crises of our times.