The UK’s decoupling delusion: Have we really divorced economic growth and carbon emissions?

The claim that the UK economy has undergone an absolute decoupling of economic growth from carbon emissions is making the rounds, and is being used to justify a ‘green growth’ narrative. But absolute decoupling is only proven if we measure emissions on a territorial basis, which fails to capture the emissions of the imported goods we consume. When we consider the whole picture, by using a consumption-based measure, the story looks very different.

Much of the debate between ‘green growth’ and ‘post-growth’ or ‘degrowth’ advocates revolves around the question of whether or not economic growth is being decoupled from environmental pressures. As we discussed in our first Escaping Growth Dependency report, for growth to be ‘green enough’ to meet climate goals, we would need an absolute decoupling of a significant magnitude. In other words, environmental pressures would have to decrease rapidly while the economy continues to grow. We explained that only relative decoupling (where environmental pressures still increase, but not as fast as economic growth) has been achieved so far, and sufficiently significant absolute decoupling would require “technological breakthroughs unlike anything seen to date.”

Nonetheless, some politicians and commentators are positing that, if we look specifically at carbon emissions, the UK has already undergone an absolute decoupling. They claim that since the 1990s, the economy has grown by two thirds while carbon emissions have decreased by approximately 40%. Yet when subjected to a degree of scrutiny, we find this claim to be highly misleading.

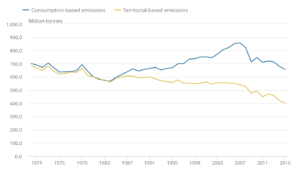

In 2019, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) even released a report on this issue, which concluded that absolute decoupling is only apparent when we measure carbon emissions on a territorial basis, i.e. emissions only produced within the UK. If we adopt a consumption-based measurement instead, to account for all emissions embodied in the UK’s imported goods, our carbon emissions increased by 30.1% from 1990 to their peak in 2007. They then dropped quite sharply with the onset of the financial crisis, returning to 1990 levels by 2015. Figure 1 shows the divergence between emissions measured on a territorial vs a consumption basis::

Figure 1: The divergence between consumption-based and territorial-based emissions in the UK. Source: ONS, 2019

As the ONS report explains, the “absolute decoupling of gross domestic product (GDP) from territorial CO2 emissions in 1986 was not solely because of policy impacts, but also because of the outsourcing of the production of manufactured goods to developing countries.” Out-sourcing our emissions has allowed the UK to deludedly pat itself on the back whilst continuing to burn through the withering carbon budget we have left.

It is also worth noting that consumption-based emission measures usually still do not account for certain sectors, such as aviation, shipping and waste, due to methodological challenges. Using a fully comprehensive measure that would account for all sectors (and greenhouse gas emissions other than carbon) would therefore show an even greater increase in emissions.

Whilst measuring emissions on a consumption basis is complex, there are many strong arguments for doing so. Most importantly, consumption-based carbon accounting is a fairer and more responsible method for establishing different economies’ carbon impact and the respective reductions needed to align with 1.5 degrees of warming. Allocating emissions to consumers means that high-income countries can’t claim leadership on climate action simply by outsourcing production to lower-income countries. Furthermore, it doesn’t penalise countries for having reserves of resources – such as aluminium or rare-earth materials – that are carbon-intensive to extract and/or refine, yet are in high demand for various uses across the globe.

Shifting to a consumption-based emissions measure would justify a drastic revision of our zero carbon target date. According to Professor Tim Jackson from the University of Surrey, if we measure emissions at their point of consumption, take uneven historical emissions into account, and consider a global carbon budget that provides an estimated 66% chance of staying below 1.5 degrees Celsius, then the UK must adopt a zero carbon target of 2030 or sooner. Meanwhile, far from showing leadership on the climate crisis, the UK government was among the many that failed to meet the Paris Agreement deadline (9 months out from COP 26) to submit updated climate action plans to the UN.

Until the government recognises and adapts to the fact that ‘green growth’ is essentially an oxymoron, it will continue to disappoint and fail to meet its already existing (relatively unambitious) targets. This may be a tough pill to swallow for policymakers and the architects of the government’s ‘clean growth strategy’, but failing to acknowledge it and grapple with its implications will only prevent real progress from being achieved.