How Money is Destroyed

As we have seen, when banks make loans, new money (in the form of numbers in somebody’s bank account) is created. What happens when these loans are repaid? Exactly the opposite – money is destroyed.

“What we were doing [through Quantitative Easing] is injecting money into the economy, and what the banking sector has been doing is destroying money [as existing loans were repaid]. As they reduce the size of their balance sheet and deleverage, they’re reducing not just the size of their assets but also the size of their liabilities. And most of the money in our economy comprises liabilities of banks in the form of bank deposits. So what we were doing was partially to offset what would otherwise have been an even bigger contraction.”

[cite]Sir Mervyn King, Governor of the Bank of England 2003-2013 (Video)[/cite]

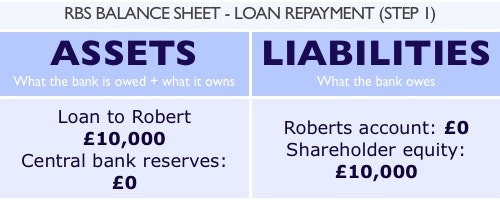

The principle is the same for all deposit money. This section explains it in terms of commercial bank money. In the example from before, Robert borrowed £10,000 to buy a car. Let’s imagine that he now wishes to repay this loan. (To keep this example simple, we will imagine the loan being repaid in one lump sum, rather than in instalments as is usually the case.)

Recall the situation directly after Robert bought his BMW: the bank has an asset of £10,000, which is its loan to Robert, and some unspecified liabilities totalling the same amount. Robert has a debt to his bank of £10,000:

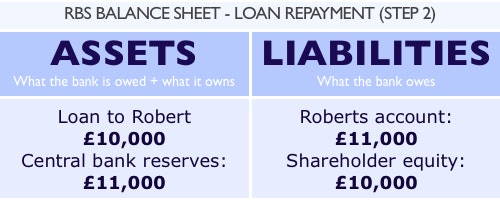

After working for a few months Robert is paid £11,000 by his employer (forgive the simplification!). This payment is made from Robert’s employer’s bank account to Robert’s account electronically – RBS gains an asset (£11,000 in reserves) and so increases Robert’s account by the same amount:

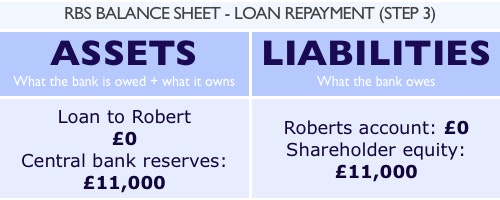

Robert decides to use the £11,000 to repay his loan in full, with interest. With an interest rate of 10% on the loan, Robert owes £11,000 in total, £1,000 of which is interest. Robert informs RBS that he wishes to repay the loan in full, with interest. From Robert’s perspective, he sees that the £11,000 is ‘taken out’ of his account by RBS. However, in reality, no money is moved at all. RBS simply decreases its liability to Robert (i.e. his bank balance) by £11,000, and simultaneously removes the £10,000 loan from its assets, because the loan has been ‘repaid’:

Robert now has no money in his bank account (RBS’s liability to him is zero). He also has no debt. RBS’s assets have increased from £10,000 when they made the loan, to £11,000 now the loan has been repaid. RBS’s liabilities have also increased from £10,000 to £11,000, however. As a result, if the bank were to now close down and sell off all their assets and settle all their liabilities, the shareholders would have £1,000 more than they had before the loan was made – this is their profit.

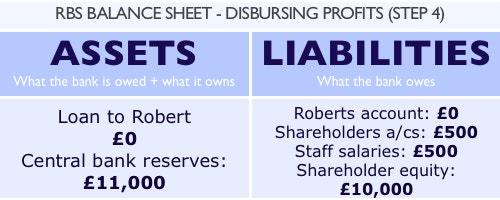

Of course, in reality the bank doesn’t close. Instead this increase in shareholder equity is likely to be used to pay dividends to shareholders, pay staff etc. For example, RBS may take the £1000 in profit and divide it equally between shareholders and staff as so:

For more details see:

Where Does Money Come From?

A guide to the UK Monetary and Banking System

Written By: Josh Ryan-Collins, Tony Greenham, Richard Werner & Andrew Jackson